DURHAM, N.C. — Nature can become a blur amid the hustle and bustle of city life, but urban trees are an important part of an urban ecosystem.

- Urban trees die faster and younger than trees in forest settings

- Just a fraction of Durham's canopy cover is actually found in the downtown area

- Trees in cities require constant maintenance in order to have a better chance at survival

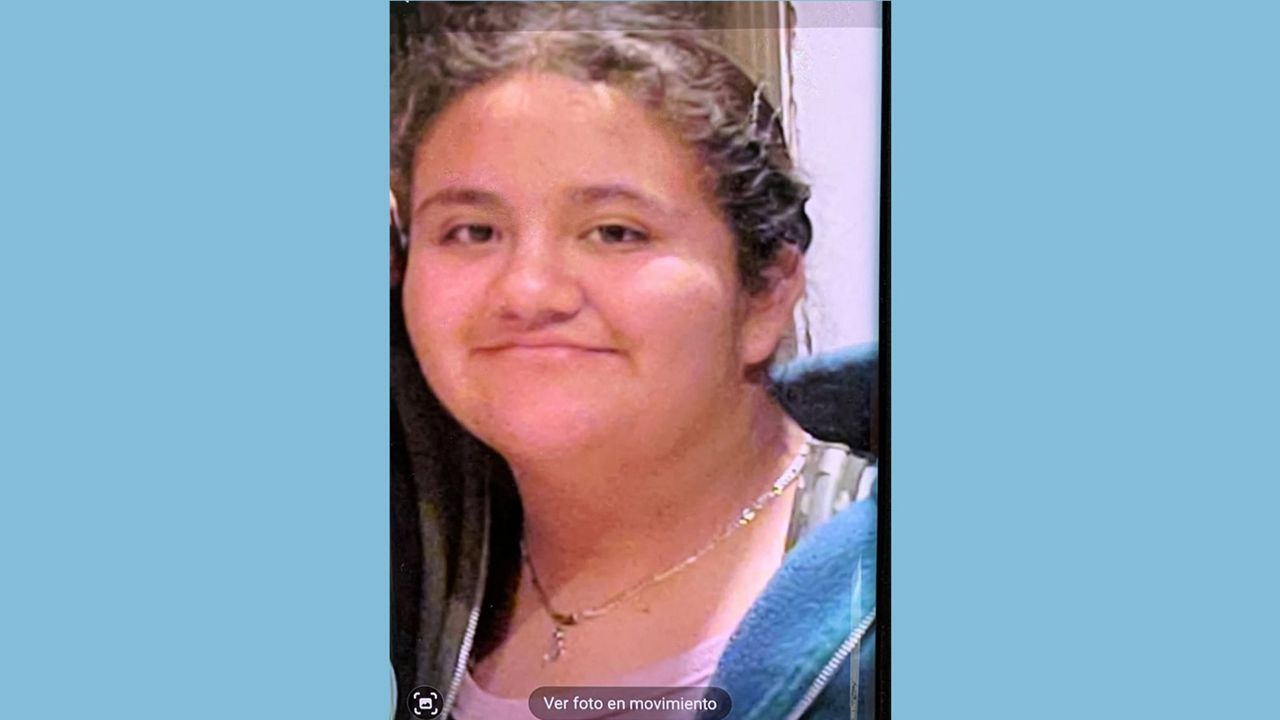

Most downtown tours focus on buildings, landmarks and history, rather than landscapes, but Renata Kamakura, an ecologist from Duke University, spends their days focused on the overlooked portion of the population: the urban trees.

“The reason I really like working in cities is that, one, I feel like I was always told that this isn't real nature, that the nature is elsewhere, and I think for a lot of people this is what they see in a day to day,” Kamakura said.

When planting a sapling, the city must take into consideration how a mature tree will impact the space – things like do the roots have enough room to grow without cracking nearby roads or sidewalks, or will the height eventually be a problem for power lines.

“Urban areas are stressful for a lot of reasons,” Kamakura said. “They deal with pollutants, low-level ozone from cars is a good example, but they also deal with extra heat, the rooting space issue, you'll have more diseases from pests, and that tends to be hard for the trees.”

Because the urban setting is unlike their natural habitat, Kamakura said we must budget and plan to support the trees we plant or they simply won't make it. Research has shown that urban trees on the whole die faster and younger than those in a forest setting.

“It takes effort to keep trees alive that long, especially in cities, so cities actually have to budget for maintenance,” Kamakura said. “If you plant a tree without the money to maintain it, that tree is not going to last very long.”

Trees generally make a city more attractive to the people that live there, giving it a homey, historic feel and reducing the heat that radiates from the multitude of buildings and expanse of pavement.

“There's actually a lot of evidence that seeing something green, even this bush, but especially a tree, will help people's mental health,” Kamakura said. “But also you can see that they're doing things to the soil to make the soil a little healthier, they also can capture pollutants in their branches or leaves and it also just makes the space feel more livable.”

As an individual living in a city, there's a lot you can do to help the urban tree population, like watering those that are on your property or a sidewalk near your home. One of the easiest ways to pitch in is simply paying attention to the tree and noticing things like broken branches or possible diseases. Reporting those details to the city can help them better manage urban forests for everyone.

“There are human areas where there are only humans and then there are areas where everything else lives, we all live kind of in concert,” Kamakura said. “How do we make it so in the future thinking about climate change, we think of cities as part of the solutions, not just part of the problem.”

_Cropped)