WILMINGTON, N.C. — Some of the biggest scientific discoveries happen completely by accident, and when a biology professor at UNCW stumbled across a working archaeological site while exploring Portugal, he found himself immersed in a research project that would span the next eight years of his career.

The Iberian Peninsula is home to the largest mercury mine in the world

Excavated bones show the earliest evidence of mercury poisoning yet

People living during the Copper Age readily used it in burial ceremonies and tribal rituals

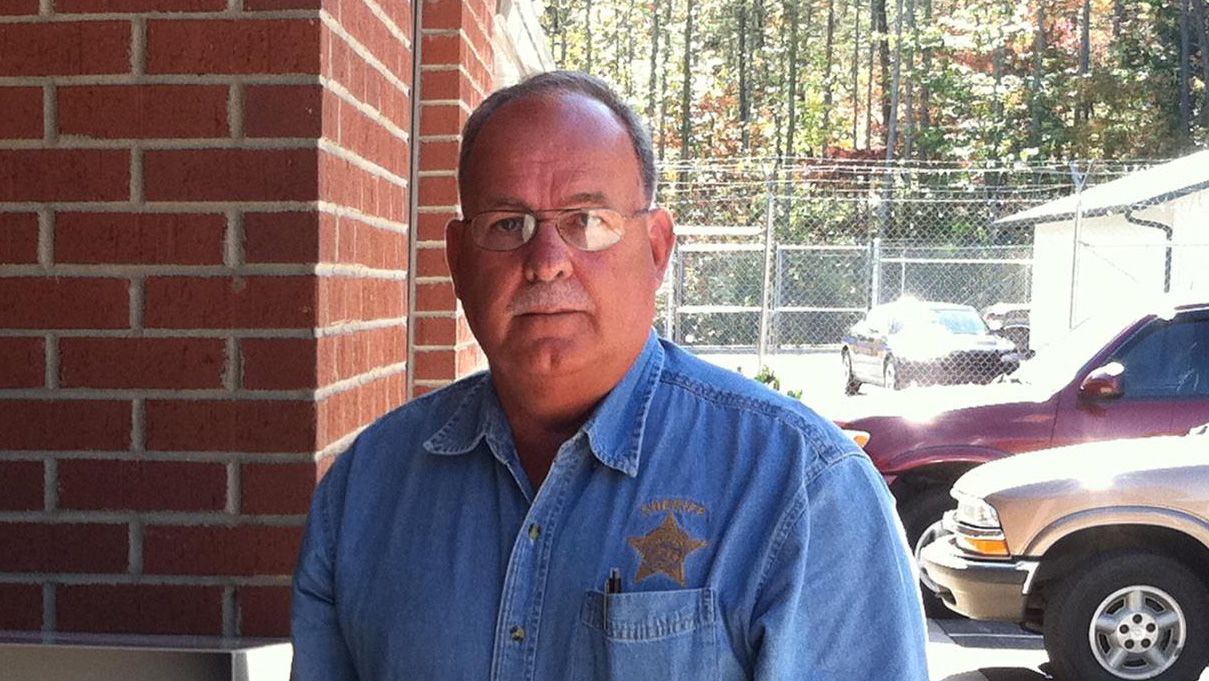

After becoming involved with the archaeological dig, in the hopes of learning more about the diet of these ancient civilizations, Dr. Steve Emslie decided to test his bone samples for mercury levels, expecting to see very low results.

“And then these bones when we first analyzed them had these huge values, and I thought at first that was an error,” Emslie said.

Prior to this, mercury poisoning was thought to be a more modern development, one not seen in centuries past, let alone dating back to 4,000 B.C. in the Copper Age.

“Some of the bones we analyzed were children, and they had very high levels, and I can't help but think that caused their death,” Emslie said.

He believes they may have associated the red pigment found in mercury with the color of blood or life – which would explain why they used it so profusely in tombs.

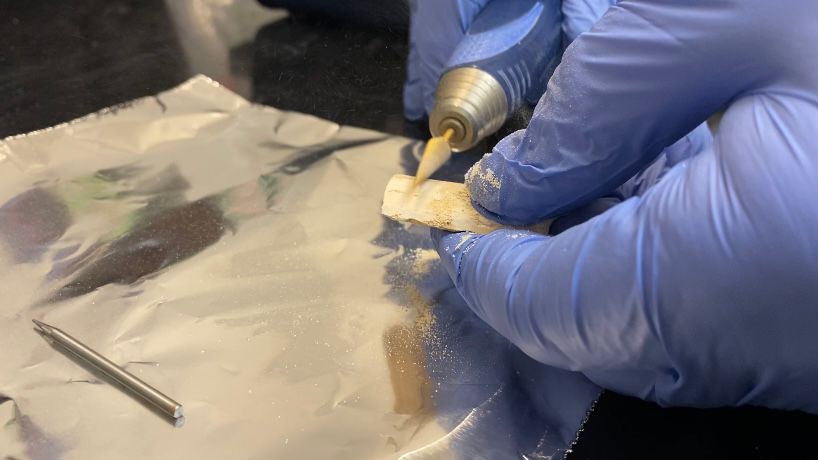

“They put it over the stones and over the bodies,” Emslie said. “If you make a paint and rub that on your skin or you breathe in this dust when you're sieving and making ore, then it will break down in your body to free the mercury from the sulfide,” Emslie said. “And that mercury then will go into your blood stream.”

Today, we frequently take in mercury through a heavy seafood diet. If mercury levels in our bodies reach 10 parts per million that's when they become dangerous, and we find ourselves at risk for side effects, such as vision loss and neurodevelopment issues.

“And some of these bones have 200, 300, 400 parts per million,” Emslie said. “That is a huge amount of mercury. Those high levels in bone imply much higher levels in your tissues.”

This groundbreaking research is just the start, and Emslie hopes it inspires others around the world to take a second look at excavated bones that may have previously been ruled out for mercury poisoning due to their age.

“We've analyzed 370 individual burials from sites ranging from late Neolithic to Roman times,” Emslie said. “These prehistoric people who had no written language are telling us something about themselves just through these types of analyses.”