DURHAM, N.C. — A young mother is happily starting a new chapter in her life thanks to donated organs.

Khadija Bond entered the national transplant waiting list primarily for a kidney but in hopes of getting a pancreas as well.

“You have to roll with the punches,” Bond said.

Bond got used to the buzzing sounds of medical equipment as she routinely went through kidney dialysis, feeling like the noise would be a never-ending soundtrack.

She received kidney dialysis at a Davita Kidney Care clinic in Durham, starting in February and running through part of the summer. It became a second home every Monday, Wednesday and Friday beginning at 6 a.m.

“Everybody knows at this point where I’m at,” Bond said. “I see them more than I see some of my family.”

Bond, 30, faced serious kidney failure and a lack of income after she was diagnosed in the fall of 2023. Because Bond endured crippling pain, she said it affected her ability to earn enough income to provide for herself and her son.

According to the National Kidney Foundation, the typical wait time to receive a new kidney is two to five years, time Bond didn’t have.

Yet at the crack of dawn, three days a week, all Bond could hear was the echo of a machine removing, filtering and returning cleaned blood to her body.

Bond said a diagnosis of end-stage renal disease can sometimes feel like a death sentence.

“It’s all good. You just have to make light of it as best you can,” Bond said.

Bond posted status updates on her social media channels during her treatments.

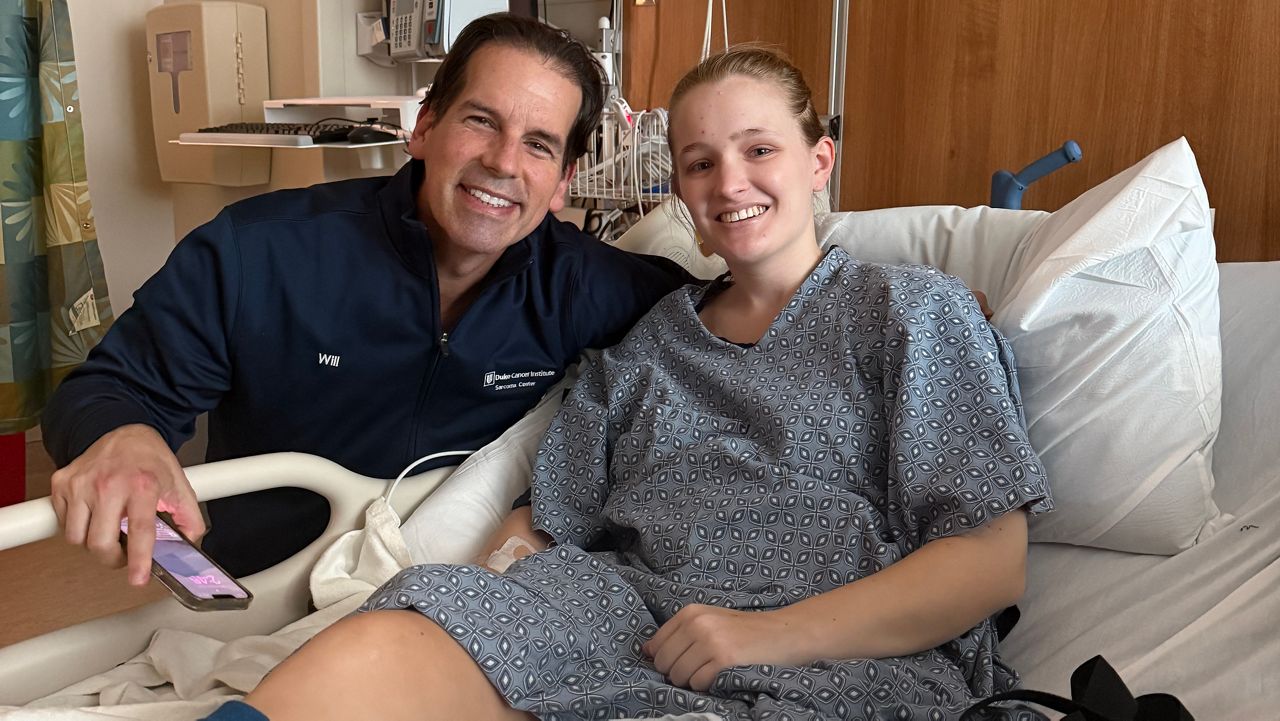

Her dream came true on July 30. Through a post on Facebook, Bond announced she had received a kidney and pancreas from an adolescent boy.

On social media, Bond wrote, “I never met you but love you so much & (I am) forever grateful for you.”

The Biden administration said it is working to better serve people in need of kidney transplants, like Bond.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced efforts to work with medical facilities to improve access to kidney donations and to combat disparities, particularly for Black Americans, in May.

That news built on last year’s announcement to modernize the nation's organ transplantation network. Overhauling a system that the HRSA reports adds a new person to the growing organ waitlist every eight minutes will take time.

Bond received a lot of help in navigating the process.

“I coordinate admissions and whatever happens during (a) patient's treatment,” said Wanda Linden, the Davita clinical coordinator at the location where Bond received her dialysis.

Linden said while they love success stories, the road to better health can be grueling during dialysis.

“They go through depression because you are working, and you have kids. You are living this life,” Linden said. “All of a sudden because of kidney failure, you have to dedicate yourself (to) going to dialysis treatments three times a week, four hours a day and then there is a downtime with dialysis after your dialysis, you won't feel as energetic.”

Linden said there’s a lot of communication at the clinic and again through follow-ups with the patients on how they are feeling. These conversations can include how well treatments are coalescing with medications and even encouragement.

“We always tell a patient that transplant is always the best option because you get your life back. You don't have to come here,” Linden said.

One of those helpers is Davita dialysis social worker Ashley Burns, who said the clinic starts every patient off with a comprehensive assessment.

“I get their basic demographics and typically, I'll talk to them about adjusting to dialysis,” Burns said. “I am the voice for those who cannot advocate for themselves. Social work is just a part of my life, and I love it,” Burns said.

She said her late grandfather died of pancreatic cancer.

“I had to step up and be an advocate for him throughout his cancer journey,” Burns said.

The N.C. Central graduate said he died on Christmas Day 2023. Burns said going through college and learning about the nuances of social work while experiencing the loss of her grandfather has given her compassion in her current role.

“It pushed me to not only be an advocate for him but for others,” Burns said.

After conducting a comprehensive assessment, Burns initiates a referral to one of four different transplant centers in the region: UNC Medical Center, the Duke transplant center, Wake Baptist and the ECU transplant center.

Burns said a dialysis patient must then undergo a series of tests, including a psychosocial exam — a barometer gauging social support, psychological well-being and lifestyle factors post-operation —- to make sure they are an eligible candidate.

She said once they determine the person is a qualifying candidate they move forward with the next steps.

“We work as a team to support the patient as far as setting their appointments up, getting them to come in for their series of tests that they have to complete for evaluation or just reaching out to see if there's anything that needs to be done,” Burns said.

Burns said Bond’s wait time was sped up by going through a dual process to receive a kidney and pancreas.

Understanding the United Network for Organ Sharing is important as well. UNOS has been the contracted vendor by the federal government for organ procurement and transplantation in America for the last 40 years.

UNOS uses everything from a potential recipient’s blood type, their level of medical necessity and the location of the nearest transplant hospital to pair a candidate to a donor whose demographics are a good match.

However, the “match run” formula has come under scrutiny over the years. While UNOS does work with 56 not-for-profit organ procurement organizations like HonorBridge to increase the amount of donors and to better service those already on waitlists, there are many who don’t live long enough to experience a new organ. The HRSA says 17 people a day die on the waitlist.

Health Resources and Services Administration data showed that of the more than 103,000 people on the National Transplant Waiting List at the time this story went to publication, 86% of the organs people are waiting for are kidneys. This makes it far and away the most sought-after organ in the country.

“I’m grateful to be here but you do have a serious health condition that’s going on that could literally go the other way overnight,” Bond said from her chair during dialysis earlier this year.

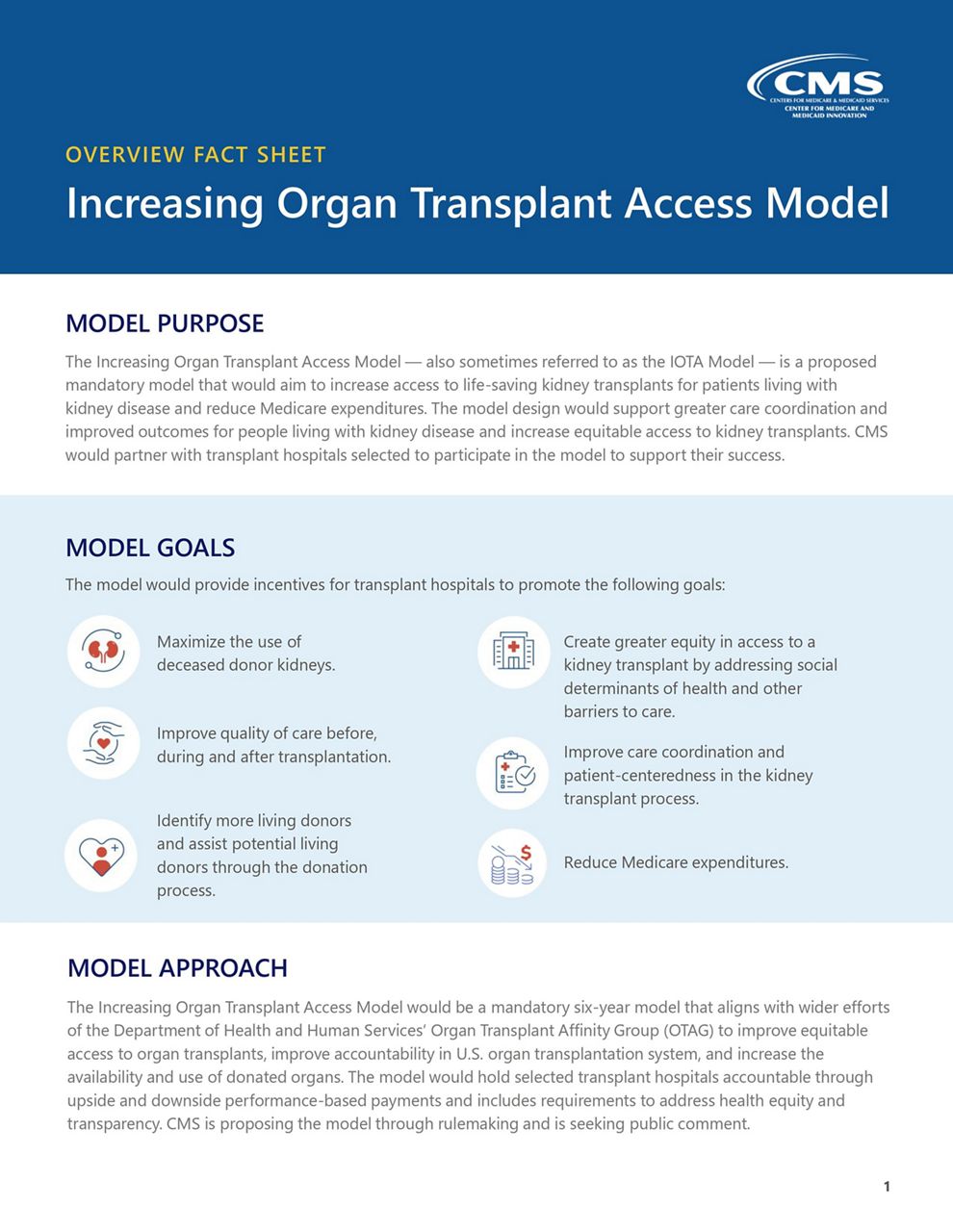

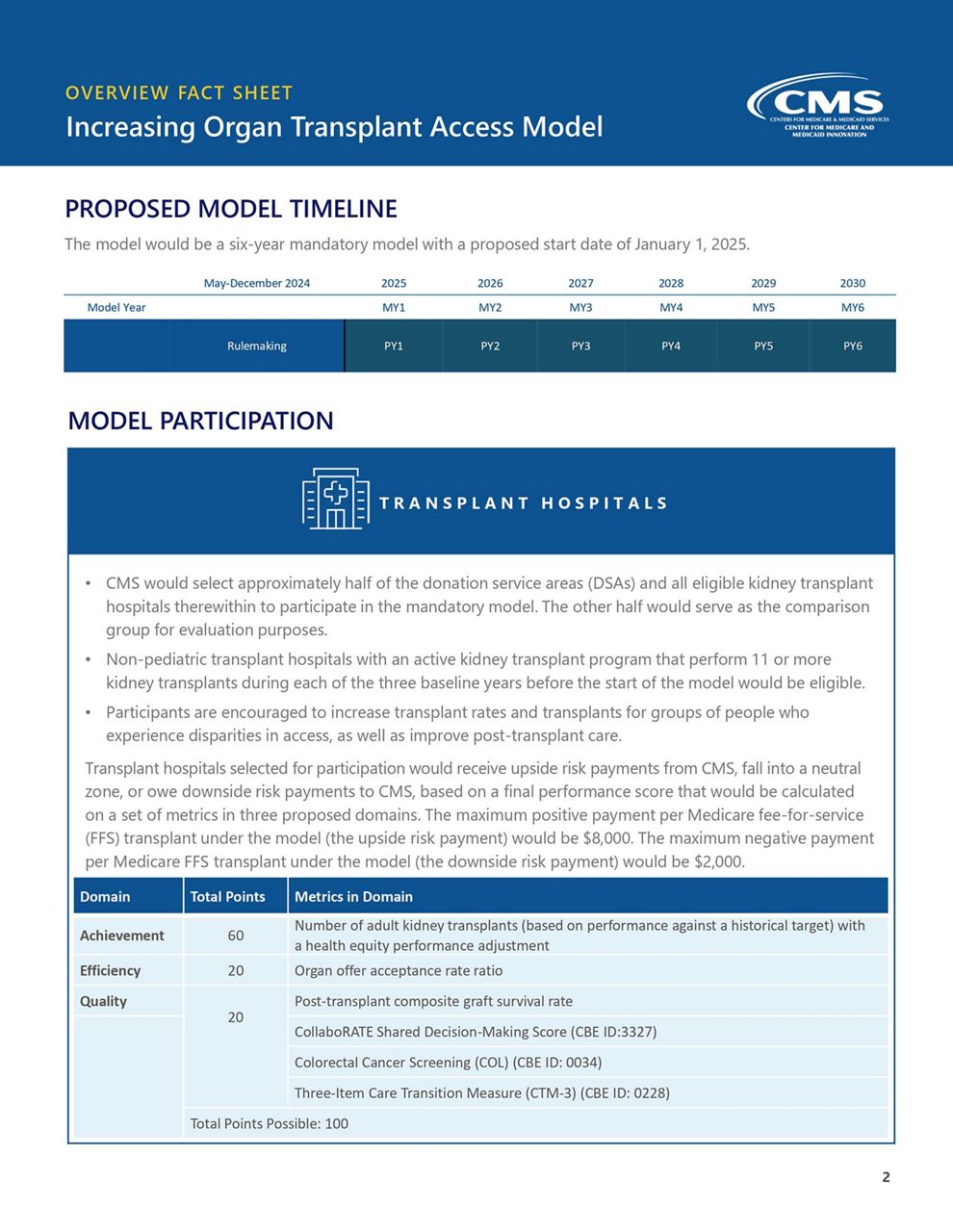

The White House pushed for increasing access to kidney transplants for all with end-stage renal disease.

An annual report on the federal Scientific Registry for transplant recipients showed roughly 27% of deceased donor kidneys were unused in 2022.

Meanwhile, the same report reveals about 32% of adult waitlisted candidates are Black. The increasing organ transplant access model proposed by the current administration would target those inequities by making transplant hospitals more accountable.

Renata Miller, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services press secretary, shared criteria for how the agency planned to do that.

Miller said the department will work with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to ensure accountability through multiple metrics, including achievement, efficiency and quality.

The achievement criteria will tally the number of adult kidney transplants performed using an adjustment for health equity. Efficiency will measure the rate of the number of organ offers accepted and quality as a criteria will measure the level of care provided by the participating hospital up to the quality of a patient’s life post-operation. The metrics will form a combined score of up to 100 with each metric given a maximum amount of points to reach.

Outside of navigating the waitlist, Bond’s life mirrors that of so many parents.

“With him, I just kind of keep it simple. He understands like ‘Mommy are you going to the doctor tomorrow? OK, good, because I want you to feel better.’ He’s handled it pretty well,” Bond said about her son.

Small responsibilities like getting her child ready for the school day bring her joy.

“Yeah, hopefully soon he will be able to do it himself,” Bond said.

Not so secretly loving every second.

“It’s just time to spend with him before the day starts,” Bond said. “It’s a lot being a mom, especially to a young child, and then not knowing the what-ifs.”

Because she said she cannot bear the thought of missing out on a hug and a kiss with her son before sending him off to school.

“I’m not going to lie and say I am superhuman. I’ll definitely have plenty of nights where I just have broken down and cry just because it’s a lot,” Bond said.

Bond never quit dialysis.

“It’s definitely scary. To say the least,” Bond said.

Yet now, she has two working organs in her body that can give her more time to raise her son.