RALEIGH, N.C. — During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, North Carolina State Laboratory of Public Health workers were at the forefront of getting people the answers they needed.

On any given day, workers were given thousands of lab tests. They performed their normal duties and others without question during some of the darkest stretches of the pandemic. Technicians, scientists and other lab hands had countless boxes of COVID-19 swabs from across the state, thrown on top of their plates while still expected to handle their usual workloads.

The N.C. State Lab of Public Health processes test samples from across the state

The public health headquarters was flooded with COVID-19 test samples during the heat of the pandemic

More than a 1,000 COVID specimens were tested a day when case counts surged due to various strains of the virus

Central Accessioning received more than 35,000 samples a month

To get a better sense of how these scientific soldiers navigated the viral minefield, Spectrum News 1 was invited into their base of operations.

Every sample arriving at the NCSLPH cannot go anywhere else in the building without first passing through a specific station called the central accessioning lab.

Michaela Harvey-Creech sees it daily. “We are busy,” Harvey-Creech said.

Harvey-Creech has been the supervisor of central accessioning since 2021 and has worked for the NCSLPH since 2011.

“I’m proud. I’m proud of what I do. I am proud of being a part of this team in the state of North Carolina,” Harvey-Creech said.

The central accessioning supervisor has worked in a few different settings. She said she was a high school science teacher for five years and has more than 20 years of experience as a medical technologist.

The State Lab of Public Health is essentially the mecca for training and consultation for other laboratories across the state. Both public and private labs in every county look to the NCSLPH as a point of reference.

The lab expert estimated a minimum of 35,000 samples flowed into central accessioning every month.

“I knew what we were doing was important and necessary,” Harvey-Creech said.“I knew what we were doing was important and necessary,” Harvey-Creech said.

Harvey-Creech said during surges in COVID-19 case counts caused by the omicron and delta variants, lab crews processed more than a thousand samples of the novel coronavirus a day.

“You just take it day by day, second by second and move forward,” Harvey-Creech said.

Each shipment to the building contains precious patient information. In order to ensure every sample mailed to the facility is handled correctly, workers follow a strict standard operating procedure. Because the amount and type of specimens are so vast, each package is received, recorded, sorted and verified. No submission leaves central accessioning without having corresponding patient data matched to a specific request. If the patient's date of birth, age, medical history and name are not listed on the paperwork then a specimen may be chunked in the trash.

“If that’s not performed then it sets everything else back,” Harvey-Creech said.

After each box is vetted by human eyes, samples are labeled with numbers unique to the patient. This numerical labeling forms the first leg of a thorough tracking protocol. Harvey-Creech said once a labeling sticker is placed on a sample, the specimen is ready to move on to its next destination.

“That label will follow that sample from the moment it leaves here all the way up to testing and actually sending out results. That number gives it, its life here at the state health lab,” Harvey-Creech said.

Everything from the receipt of the orders to the result of the tests is tracked, including in between when samples land in the reagent prep room.

In this second-floor room, technicians set up the substances or mixtures to extract specimens from a nasal swab to confirm or deny the presence of COVID-19.

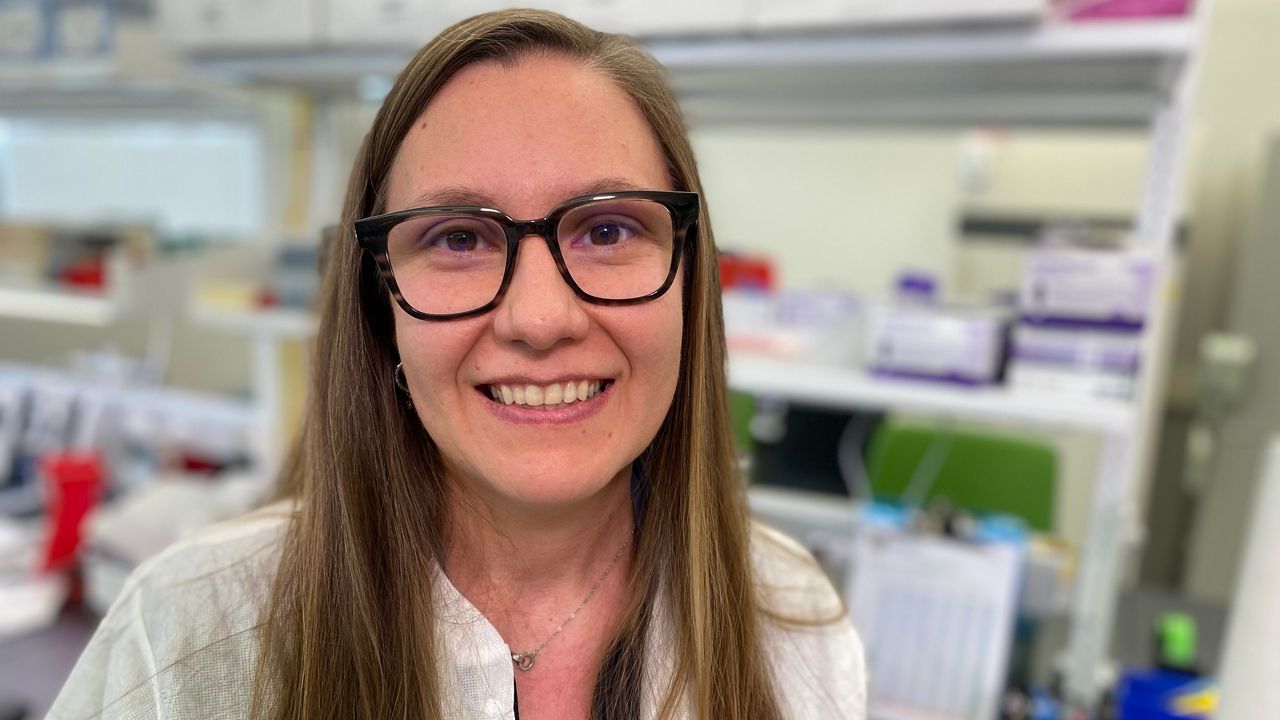

The manager of the NCSLPH Virology and Serology Unit, Dr. Rebecca Pelc, said their mission fulfills a lifelong dream.

“I always had the interest in being part of something that is helping people,” Pelc said, adding that giving birth during the pandemic drives that message home for her.

Their devotion to their craft is so strong, Pelc said she was on her feet working in the lab when she was nine months pregnant.

Like so many faces of COVID-19, toiling on the frontlines, she pulled long hours, sometimes deep into the night. This kind of sweat and hustle became the norm for many during this time.

Some scientists, like Kitty Chase, brought years of expertise to the table.

“You’ve gotta depend on each other. Battle buddies. That’s exactly what this was like. Going into battle,” Chase said.

Chase understands preparing for scientific warfare. The Massachusetts native worked in the health lab of her home state before moving to Maryland to work as a civilian in an Army lab.

“When I worked in Maryland at Fort Detrick, I worked on tests the same as the tests for COVID,” Chase said.

She said working alongside America’s finest taught her the importance of efficiency.

“You learn to work efficiently, you learn to walk fast and you learn to keep calm under pressure,” Chase said.

In her day-to-day job title, Chase is a lead bioinformatician. Bioinformaticians deal with numerous forms of biological data each day. Instead of only taking care of bioinformatics, she volunteered to be a tester.

“I really saw that they were short-staffed and figured I have experience. I’ll help out, and those were my famous last words,” Chase said.

She chipped in years of know-how to sift through thousands of COVID-19 tests each day.

“There were times I was the only one doing the testing — and I know if I didn’t do all those tests, there’s a lot of people who would have no idea how sick they really were. I wanted to be there for the citizens of North Carolina,” Chase said.

She said she continued working hard under pressure.

“But a breaking point? Not really. Because I had a great team. I mean, this is where you learn to count on your lab mates,” Chase said.

Their fearless leader

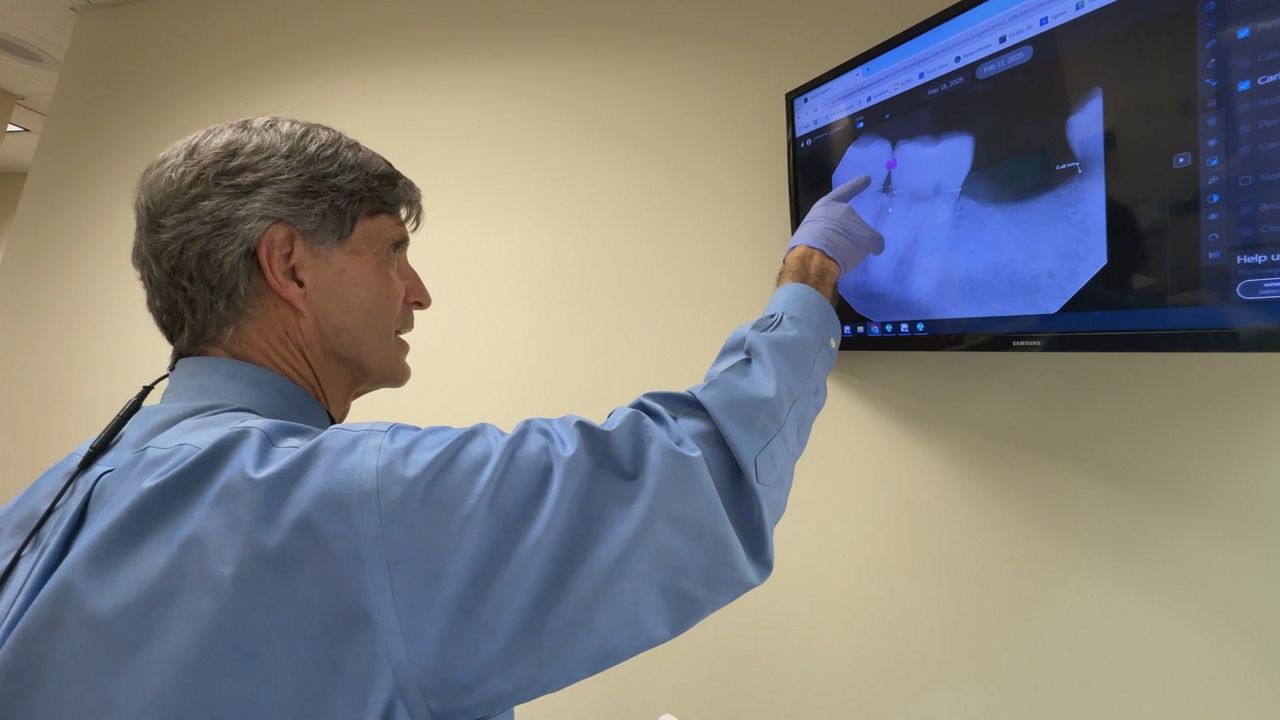

Running the biggest public health lab in the state is not a job director Scott Shone takes lightly.

Shone, 46, a New Jersey native, said the lab's ability to maneuver through the COVID chaos has made them a model for the nation. Recently, the director gave a presentation on their workflow handling of testing swabs and game plan to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

He believes their efficiency will be a template for success for other public health labs across the country. He took the role of director and head of operations in September 2019, months before COVID-19 emerged.

“It was really a trial by fire and jumping right into the deep end,” he said.

Shone found himself in a remarkable position. Not only was he in charge of operations, but the lab director was also accountable to the governor and then-Health Secretary Mandy Cohen for turning complex science into clear wording the public could understand. Shone described how the interest level and engagement from leadership made communicating the science behind decision-making much smoother.

“I think that was part of the challenge we had, is that we really needed to think about how to get the message across accurately but meet people where they were, both with what they were ready to hear, but also how they needed to hear it,” Shone said.

After all, state leaders based important life-altering public health policy decisions, such as stay-at-home orders and masking, on their scientific data. Shone said he was fortunate to have some honest, good people in his corner.

“I was surrounded by really great people who were like you can’t use that word. You can’t say it that way. People aren’t going to grasp it,” he said.

Shone and his staff weren't immune to the worries of the pandemic, though.

“I was constantly concerned that I would bring COVID home,” he said.

But he never did. The fear of infecting his wife and two sons could not replace the joy of being with them, he said.

“It was always comforting to just sort of like sit on the couch and just be with them and realize that we would get through it,” he said.

Shone said their blueprint for teaching professionals and the public to understand different types of testing, what to test and when to test has shaped national guidance at the federal level.