CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — Firefighters have a 9% higher risk of being diagnosed with cancer and a 14% higher risk of dying from cancer than the general U.S. population, according to research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety.

Researchers from UNC and N.C. State are teaming up to figure out how PFAS chemicals could be contributing to those cancer rates.

Firefighters take on the responsibility of running toward danger.

“I fell in love with this from a very young age. I am fourth generation. My father did this, and I saw how much fun he was having, and I said I want to partake in that myself,” John Wellons, the battalion chief for the Chapel Hill Fire Department, said.

There’s often one thing they keep in the back of their minds: cancer.

“We’ve had people come down with kidney cancer, we’ve had people come down with testicular, thyroid,” Wellons said. “It’s almost like you wonder at what point is it going to be here. What time is it going to show up?”

Chris Wells, the assistant chief of life safety for the Chapel Hill Fire Department, knows that situation all too well.

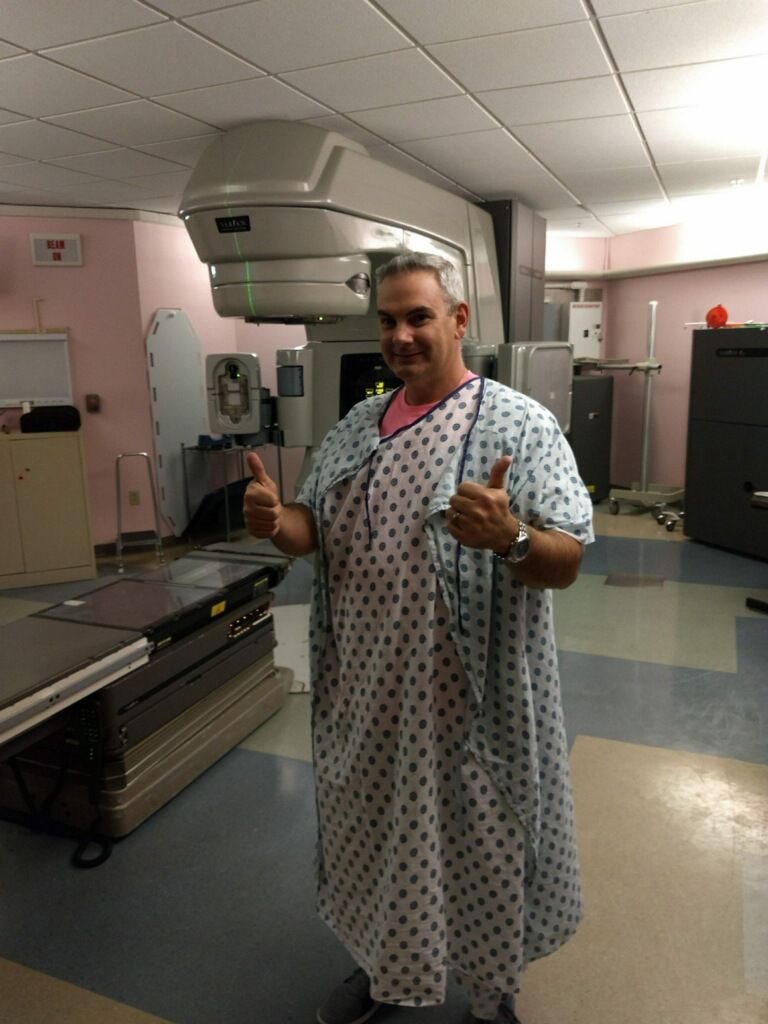

“In 2018, I was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. I was at that point, about a 21-year veteran of firefighting and fire service,” Wells said.

Wells feels fortunate to now be cancer-free, but that diagnosis was life-changing.

“At a young age to have a young child and a family, the rest of your career, all of those things you kind of look for in your early 40s. It’s definitely not something you’re expecting is a cancer diagnosis at that age,” Wells said.

So what’s causing cancer in firefighters? UNC and N.C. State researchers are looking at PFAS chemicals.

“PFAS can cause cancer and it can also cause adverse birth outcomes,” Dr. Barbara Turpin with UNC’s Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering said. “[PFAS] are used in so many different things. They’re used in the protective gear that firefighters use when they go to a call. They are used to make carpets and couches stain-resistant. They’re often that nonstick coating in pans.”

Fire departments have different decontamination, also known as decon, policies in place.

“What they do is they will take these [wipes], they will break these open and is there for them to clean their necks, their face and their hands and any other soft tissue areas they have that’s been exposed. That’s the first stage,” Wellons said.

There are different procedures to make sure their gear and bodies are thoroughly cleaned after responding to a call.

“Even our other stations have the option of cleaning themselves before they ever go into the living area,” Wellons said.

But those decon policies may still not be enough, which is why Turpin and other researchers are studying exposure to PFAS.

“We’re going to measure PFAS in air. We’ll also measure PFAS on surfaces. We’ll put some little samplers in the truck that collect with time, passively. We’ll sample in some convenient ways like we’ll take the air conditioning filters and we can analyze those,” Turpin said.

Their findings could help influence how fire stations are built in the future, how uniforms are designed and even change decon policies to make them more effective.

Wells says the Chapel Hill Fire Department is more than willing to help with the research if it means even one less firefighter has to go through what he went through.

“Many of us know those folks that we had mentioned before that have been diagnosed or had been diagnosed with cancer and so we do it for each other and do it for them to kind of reduce those numbers,” Wells said.

This work by UNC and N.C. State is funded by the North Carolina Collaboratory and the N.C. General Assembly. The research has the potential to reach far beyond North Carolina. The study will likely take several more months and then it could take another year to analyze and interpret the data.

_crop_1)