FAYETTEVILLE, N.C. — A martial arts program is helping children with developmental delays and autism, especially for one North Carolina family.

What You Need To Know

- The Martial Arts of North Carolina dojo offers an adaptive jiujitsu class

- Children with developmental delays, autism or who are sensory-sensitive attend

- Many military families living near Fort Bragg after losing medical coverage for certain therapeutic benefits are impacted

- Tricare, the health care program designed by the Department of Defense, steeply cut applied behavior analysis benefits

- The Martin family signed up for the course when other therapeutic avenues closed

Tuesday afternoons in Fayetteville are one of Mia Martin’s favorite times of the week.

The 12-year-old girl, who has autism, hops, runs or back pedals her way through an adaptive jiujitsu class at the Martial Arts of North Carolina Dojo.

The rules are specific to every child’s sensory needs.

“Can I have a sticker?” Mia Martin asked after she finished an exercise.

These days, the teenager often talks in complete sentences. The middle schooler has developed stronger language skills, despite being diagnosed as a non-verbal communicator with autism at a younger age.

Her small verbal observations are taken as a major sign of progress for her father, James Martin, who understands executing a mission.

“It’s been awesome,” James Martin said. “This is probably the one activity that challenges her emotionally, mentally and physically for a sustained period of time.”“It’s been awesome,” James Martin said. “This is probably the one activity that challenges her emotionally, mentally and physically for a sustained period of time.”

James Martin is an Army veteran who has served in the theater of war in the Middle East. He said this class builds on his daughter's speech and behavioral growth outside the studio.

Looking high and low for therapeutic ways to help his daughter adapt to the world is a never ending quest for the Martins. Like many servicemen with a child on the autistic spectrum, the retired soldier is painfully aware of the limited options he has with his government funded health care, called Tricare.

With so few therapeutic outlets available, the doting father paid out of pocket for this class and believes it's worth every penny.

“She gets a full body workout. I would say it’s improved her cognitive ability,” James Martin said.

Changes to Tricare limited or eliminated many therapies. According to the Defense Health Agency’s website, “The DHA Autism Care Demonstration (ACD) manual changes were published on March 23, 2021.” Families were notified changes would take effect May 1 of last year. The biggest alteration to policies and benefits happened to applied behavior analysis, or ABA, services.

Parents interviewed by Spectrum News 1 said ABA could no longer be effectively used at school or in the community.

In the past, a statement from the DHA said the loss of medical coverage for ABA is backed by science. Last fall, a DHA spokesperson wrote, “It was never the intent to reimburse for non-clinical or educational ABA services.”

James Martin said their family qualified for a second insurance policy to cover more of the cost of ABA services that Tricare would not.

Since the Martins were left with no choice but to search for better options, they brought their youngster to the martial arts dojo.

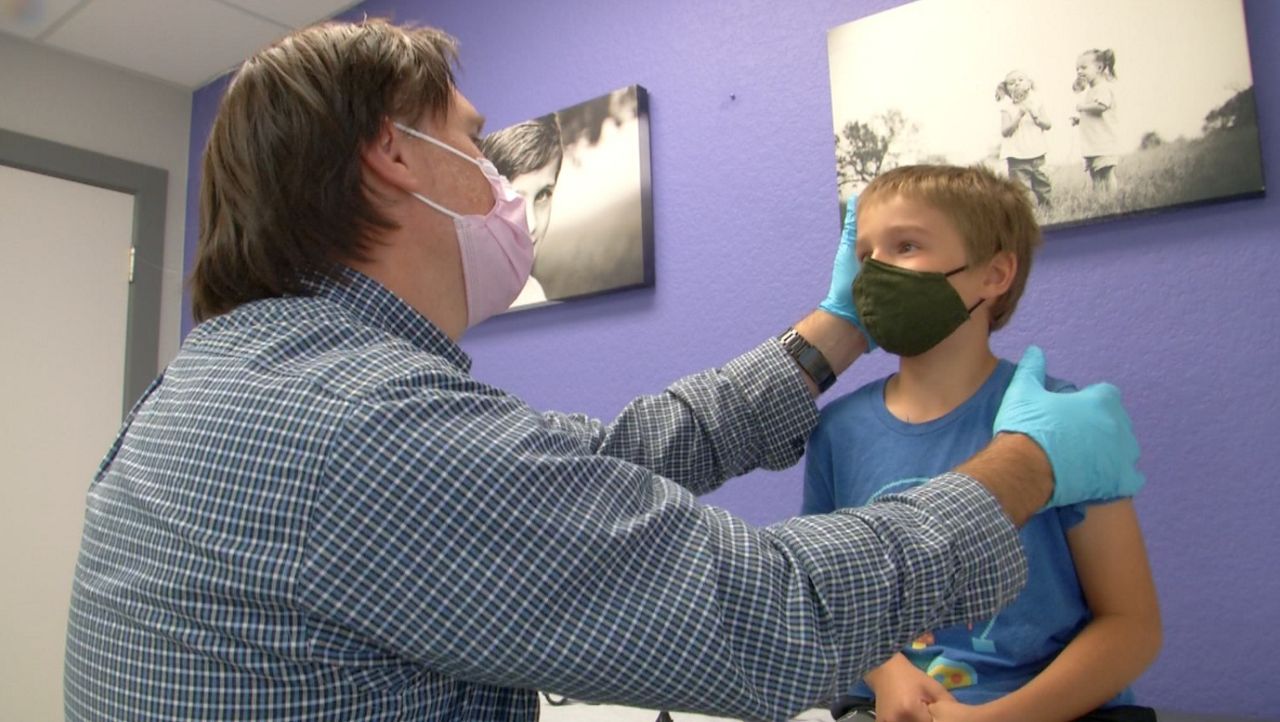

In April, when Spectrum News 1 was on-site for this story, Emma Shields was their lead instructor.

Shields, 29, has a background in recreational therapy, grew up with a brother with autism and was the gym’s full-time manager.

“When a lot of these kids first started they didn’t have that independent skill there to just know to move ahead with class. They needed one-on-one direction,” Shields said. “They needed a lot of physical prompting.”

Shields said she couldn’t run this course without Bersuada Saunders-Clarke. Clarke’s experience is in integrative sensory therapy, which complemented what Shields brought to the table.

Because children with developmental delays and those with autism may have trouble communicating their own thoughts, visual supports, in the form of pictures, comes in handy.

Their instructors pinned photos of the exercises on a board to create a starting point. There are many times when Saunders-Clarke used it.

“They kind of know the routine based on the visual,” Saunders-Clarke said. “The visual prompts really help with setting structure and routine. Sometimes you need to really have that visualization so that you can go ahead and see what it is that you are being directed to do.”

The 45-minute training sessions amplify the behavioral work and therapy students do outside of class. Instructors said it’s important for students to engage their bodies in order to use their minds.

For people with autism and certain sensory sensitivities, the brain has a hard time understanding what it sees when the body feels under attack. Shields said repetition breeds familiarity.

A weekly routine of physical activity creates an internal sense of safety for these children. When students can emotionally regulate their central nervous system, the CNS sends calming signals to the brain from the body and makes sensory processing of information by the brain easier over time.

“Now we are here and they are so successful working independently, where they can follow these directions and they can get their classwork done. It’s really awesome,” Shields said.

Several months into training, Saunders-Clarke and Shields each said these pupils are on the verge of running the drills themselves.

“Seeing how these types of things actually create a difference in your ability to focus, your ability to socialize and have just a moment when you are focusing on something that has an end goal and great outcome,” Saunders-Clarke said.

Which is the kind of independence Martin wants to see his daughter reach. “It’s definitely helped get her out of her shell, which has been super helpful,” James Martin said.