HALIFAX COUNTY, N.C. — Principal Steve Hunter checks the news often, feeling mixed emotions after learning a judge has decided the state should invest hundreds of millions of dollars more into public education but didn't say how.

A newly-appointed judge has ruled on a decades-long education funding case

The judge says the state owes North Carolina education funding more than $785 million

Some education leaders are anticipating the long-awaited funds

It's the latest ruling in a decades-long education funding case called "Leandro," which could allow his school district to receive between $15 million and $20 million.

“It’s been over 30 years, so I’m not going to hold my breath. But, we have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst," Hunter said.“It’s been over 30 years, so I’m not going to hold my breath. But, we have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst," Hunter said.

The Leandro case started in 1994 when a group of families sued North Carolina, saying it was not providing their kids the same opportunities as other higher income school districts.

In a landmark ruling last year, a judge said the state was not holding up the previous Leandro ruling to provide adequate education for everyone and, therefore, the state needed to invest $1.75 billion in schools.

The Republican chief justice of the state Supreme Court then decided to replace the judge who made that landmark ruling with Superior Court Judge Michael Robinson.

On Tuesday, Robinson ruled the state owes North Carolina more than $785 million in education funding.

However, unlike the previous controversial ruling demanding immediate funding, this decision does not lay out how the money will be made available.

Hunter grew up in Halifax County, graduating from Northwest Halifax High School in 1987.

“It’s a humbling experience to walk around a campus where I used to walk around as a student 30-something years ago," he said.

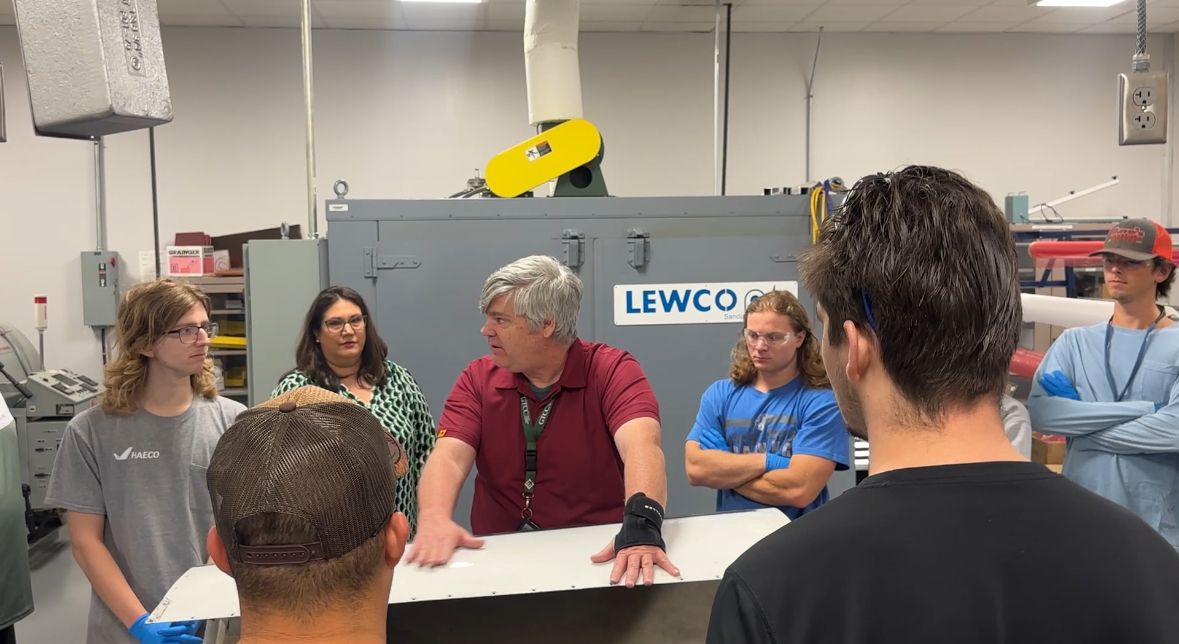

Three decades later, Hunter never imagined students here would still be faced with a severe lack of resources. For instance, the school offers only five CTE, or career technical education, classes.

Hunter says other districts in more affluent areas can offer 25 classes or more.

“We would like to move into the direction of offering students an HVAC program, heating, air conditioning and so forth. We want to offer our kids a skill to serve as a plumber, how to become licensed electricians, but those programs require money," Hunter said.

What also requires money, Hunter says, is a lab for science classes and updated equipment.

“The microscopes [used in the class] were here before 2000, so they are at least 22 years old," he said.

At the elementary school down the road, Hunter says students can take a foreign language. At the high school, the only instructor you’ll find is virtual.

“It’s difficult to learn a foreign language, but it makes it more difficult to learn a foreign language with a teacher who could be 50, 60, 200 miles away," he said.

For all these reasons and many more, Hunter is praying politicians understand the future of students is what's at stake. He says money means opportunities, opportunities all students should have access to.

“I would like for the politicians in our state and for the judge in our state to think about our kids. Put our students first. Because the more our kids are able to achieve, the better our state will become and our nation, and throughout the world," he said.