DURHAM, N.C. — You don't generally think about trees migrating like other species, but they do and as climate change makes some of their current habitats unsuitable, the ability to relocate is more important than ever.

What You Need To Know

- Changes in climate are forcing trees to migrate to more suitable environments

- Seed production largely determines how quickly a tree is capable of migrating

- The research has been collected from forests all across the country

A team of researchers from Duke University is looking at what factors might influence our forests' ability to keep up with warming temperatures.

Jim Clark began collecting data on seed production 30 years ago, never imagining the study that would be enabled by that longterm research.

“Because we've got such a large network of detailed plots, we've been able to look at things like how variation in climate and habitat, across the network, but also year-to-year variation, things like droughts - those are the kinds of things we couldn't have done without this type of approach,” Clark said.

Although our forests in the East are younger overall and have a higher seed production, they're not migrating as quickly as forests in the North and West. Clark attributes that to less harsh climate change happening in the Eastern region of the U.S.

“The fastest they can move is limited by how much seed they produce and how far it gets dispersed,” Clark said. “In a way, the fact that you've got this massive seed production here in the Southeast is not really the place where you need it most.”

Tree migration can be extremely complicated due to the specific environments many species need to survive. Die-backs of certain species have already happened in years past as they failed to adapt quickly enough to both human and natural changes in their ecosystem.

“If you don't know what's going to happen as the climate's changing, then you can't predict new species interactions,” Maggie Swift, a Ph.D. student at Duke said. “It might move to an area that's great for adult trees but not great for young trees, so it can't reproduce even though the adults are doing fine.”

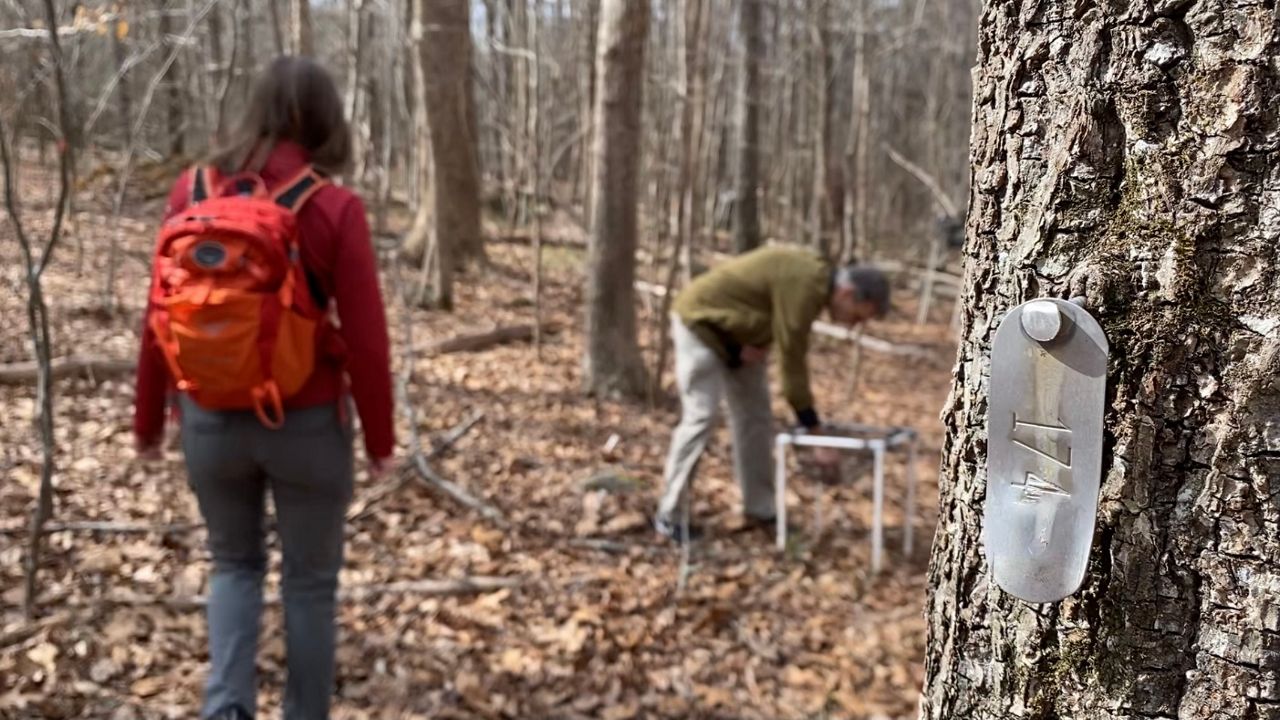

Clark and his team are using seed traps in Duke Forest to monitor seed production in various stands and compare that data to other researchers all across the country taking part in this study.

“We measure all the trees every three to four years, we empty the seed traps twice a year,” Clark said. “We're learning about which species produce a lot of seeds, which individuals within a species produce a lot of seeds. There's a huge variation.”

This project started out at Duke Forest and slowly spread across North America to allow for comparison. Their sample size includes hundreds of thousands of trees, representing more than 81 species and more than 500 longterm field research sites across the nation.

“The first thing to do is try to understand what are the changes happening now, and if we can understand that, then we can use that to try to look forward,” Clark said.

The wide range of data allows them to gain perspective on how the big picture of biodiversity is shifting as well as begin to consider whether a human solution should be used or continue to let nature run its course.

“In the past it was called assisted migration – should we be moving, planting in this case, species outside their native range to anticipate the climates that they might find suitable in the future,” Clark said.