CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — Children ages 5-11 can start receiving protection against COVID-19 some time this week as a CDC committee approved Pfizer vaccinations for the age group Tuesday.

UNC Children's Hospital granted access to their pediatric intensive care unit for the first time during the pandemic

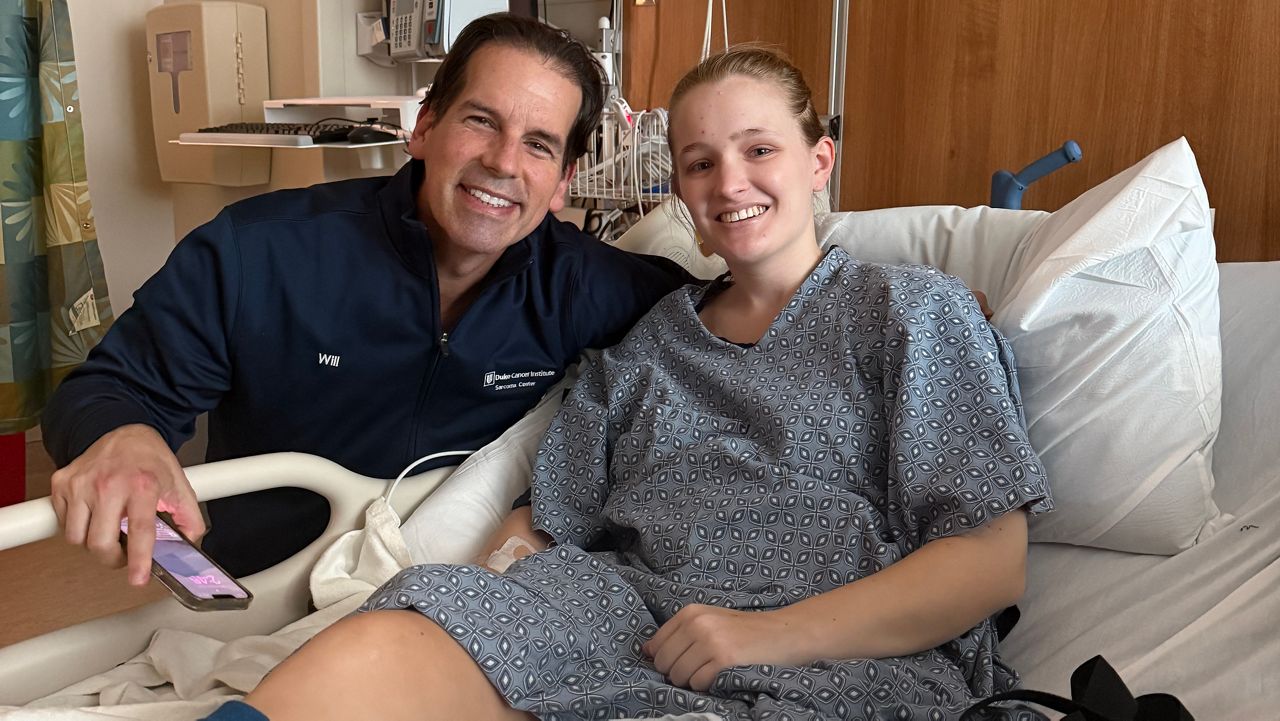

Dr. Benny Joyner is the chief of the PICU and has worked in the unit since 2009

Since the July surge, 73 pediatric patients have been treated for COVID-19 in the hospital

The unit's top doctor feels approval of the vaccine for children ages 5-11 will be a nationwide game-changer

The FDA gave its blessing last week. Pediatricians say total approval from both federal agencies is a game-changer in the fight against the novel coronavirus.

For moms and dads, it’s a chance to keep their sons and daughter safer than they were before. A doctor who runs the critical care unit at UNC Children’s Hospital in Chapel Hill wants to keep as many kids who are sick with the virus off the floor as much as possible.

Dr. Benny Joyner has been the head of operations in the pediatric intensive care unit for several years.

“I think that life in the ICU is always fairly hectic. Even pre-pandemic, it’s generally pretty busy. There’s life-and-death issues that we’re trying to understand, and trying to help families understand on a day in-and-day-out basis,” Joyner said.

The chief of the unit has seen a lot since he started working here in 2009. He admits there isn’t a real one-to-one comparison for treating children who have COVID-19.

“The kids that have come (in here), especially those with COVID that have come into the ICU, have been extremely sick,” Joyner said.“The kids that have come (in here), especially those with COVID that have come into the ICU, have been extremely sick,” Joyner said.

Their threshold for care was tested during the summer months when cases of COVID-19 surged in July.

“We have increased our utilization of life-saving therapies tremendously,” Joyner said. “We’re utilizing therapies and the volume of therapies that we have utilized that’s been in ways before the pandemic didn’t exist.”

At the peak when the delta variant of the virus spread across America in September, the lead physician said 40% of patients were on extracorporeal life support. ECLS is more commonly known as ECMO.

According to the Mayo Clinic, “In extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), blood is pumped outside of your body to a heart-lung machine that removes carbon dioxide and sends oxygen-filled blood back to tissues in the body.”

In this ICU, there are only 20 beds. Eight out of 20 children experiencing serious respiratory and/or heart failure is no small take.

“I think that’s been the biggest change is trying to account for that, trying to plan for the unknown. There’s still so much that we don’t understand about COVID and its impacts on kids. And so, we are seeing these kids coming in sicker and sicker,” Joyner said.

Data confirmed by hospital staff showed UNC Children’s Hospital has treated 73 pediatric patients with COVID-19.

The virus doesn’t have to infect every patient here for it to impact care for all of them.

“There is no other way to sugarcoat it. It’s really challenging both emotionally and intellectually,” Joyner said.

COVID-created challenges

He says serious staff shortages, nurses getting sick, the sheer amount of patients with varied illnesses and the realistic ability to care for patients who may or may not have COVID-19, creates a sophisticated challenge to the level of care the team can provide.

There are times when Joyner has felt rundown as well.

“If I’m being honest, probably, yes. There have been times when I have to take a break just like everyone else. It’s really hard to do this for 20 months, and so there’ve been times when I’ve had to take this opportunity to just disconnect and say, ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” he said.

Anyone who works the floors learned over these months the importance of self-care.

“Have I hit my limit on occasion? Yes. I think that’s where it's important to take time out to remember why you do this and spend time with family,” Joyner said. “However I do feel it’s really important, the service I provide. I do feel like it’s important that the care that we deliver here at the children’s hospital, that it go on.”

Other COVID impacts

The element of true in-person connection has often been taken away as well. Video conversations with parents, pending a reliable Wi-Fi connection, are a common way to communicate sensitive medical information. There are moments when the doctor had to deliver end-of-life news about a child when he couldn’t tell parents face-to-face.

“We’re not allowed to be as up-close and personal, that’s the human touch, the human factor, especially with families. That’s family visitation has been limited. We’ve been doing more virtual conversations. I like to look at somebody, I like to engage in a conversation and sit down and be on their level, read their body language and interact with them,” he said.

The patients who come through these doors could be here for days, weeks and even months.

He said wearing a white coat hasn’t gotten any easier since 2020. Especially when not every child makes it out alive.

“I think, independent of COVID, I think the death of any child weighs on you and impacts and changes you,” Joyner said.“I think, independent of COVID, I think the death of any child weighs on you and impacts and changes you,” Joyner said.

At any given time throughout the day, the shrill sound of a baby crying can pierce through the sounds of machines buzzing and beeping on the floor.

Fatherhood molds how he views the care he provides for his patients.

“This is pre-pandemic, but I still remember taking care of a 9-month-old, and it was at the same time my daughter was 9 months old. It was my first child and (I) just (remember) really being struck by the fact that this could have been my daughter,” he said.

Bedside manner is everything when you are the one talking to moms and dads. He says when they are emotionally teetering on the edge, he has to be confident in himself that he is doing the right thing.

“To look at you and say, ‘I am doing all that I can.’ I’ve asked all the people I’ve needed to ask, and this is what I can do for you, and if you are upset that is OK, because I would be upset too if this was my child, and they weren’t getting better,” Joyner said. “As I think about the relationships that I have formed when I have shared the joy when someone is getting better or shared the sorrow of someone who has passed away. Those are very special moments that not too many people get to share. Those are moments that you share with immediate family.”

There is also the element of constantly dealing with misinformation about COVID-19. At the time this story was published, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services listed the eligible population of people vaccinated in the state at 65%. With the possibility of children younger than 12 receiving the chance to receive the first dose soon, there are plenty who already have the opportunity who haven’t taken the jab. He shared moments like this as an example of the disconnect between the facts and pure fiction.

“We had four patients in here at one time: all adolescents, all overweight, all unvaccinated. They are all like, ‘you know my friends got vaccinated, and they didn’t get sick.’ I'm like, ‘I hear you. I hear you,’” Joyner said.

He pointed to and confirmed the rooms of at least three COVID-19 patients the day he was interviewed. At one point, he wasn’t sure the numbers would take a real dip.

“While, yes, on one hand, we’re sighing a huge sigh of relief, breathing a huge sigh of relief at the fact that we are actually coming down on our COVID numbers. We still are worried about what the winter will hold,” Joyner said.

What gives him hope is FDA approval of the Pfizer vaccine for children ages 5-11 because he is a father.

“It's always a relief to be able to say maybe there’s a light at the end of the tunnel,” he said.