This article is an extension to our series titled “Exploring Your Health,” which breaks down the complex science, issues, and policies behind some of the most important health questions and what we can do about them. Watch the full episode on how modern culture is pushing women to delay pregnancy as science tries to catch up, here.

The egg freezing business is booming. More women are seeing it as a comforting insurance plan that may allow them to be their own egg donors in the future. In order to determine the type of medicine a woman will need to take and the dosage necessary to stimulate egg growth to retrieve the eggs for freezing, blood is drawn and the level of antimüllerian hormone (AMH) is measured. It is a snapshot of whether a woman’s ovarian reserve is high or low.

Some egg freezing services offer the test as a way to help women determine whether they should freeze their eggs. But the test is not an accurate predictor of future fertility, because what matters most is whether the majority of a woman’s egg supply is healthy.

Our National Health Reporter Erin Billups sat down with a reproductive endocrinologist, someone who specializes in fertility and fertility-related problems, from Yale Medicine to discuss the current science surrounding egg testing and options for women who may want to wait until later in life to get pregnant. The below conversation is edited for clarity and brevity.

Erin Billups: Why shouldn’t women use an AMH score to determine their egg supply for future use?

Dr. Amanda Kallen: “If I have a patient who comes into my office in her 20s or 30s and she is just thinking, ‘you know I've never tried to get pregnant I'm not planning pregnancy right now, what's my fertility like?’ I don't recommend getting an AMH. If she comes to me and she's already had her AMH checked, I will say that it doesn't necessarily mean you are going to have trouble once you try to get pregnant.”

Dr. Kallen points to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association out of UNC Chapel Hill where the AMH levels of 750 women with no history of infertility were taken. There was no association of reduced fertility between women with normal AMH levels and those with lower levels.

EB: Is there a way to test the quality of our eggs?

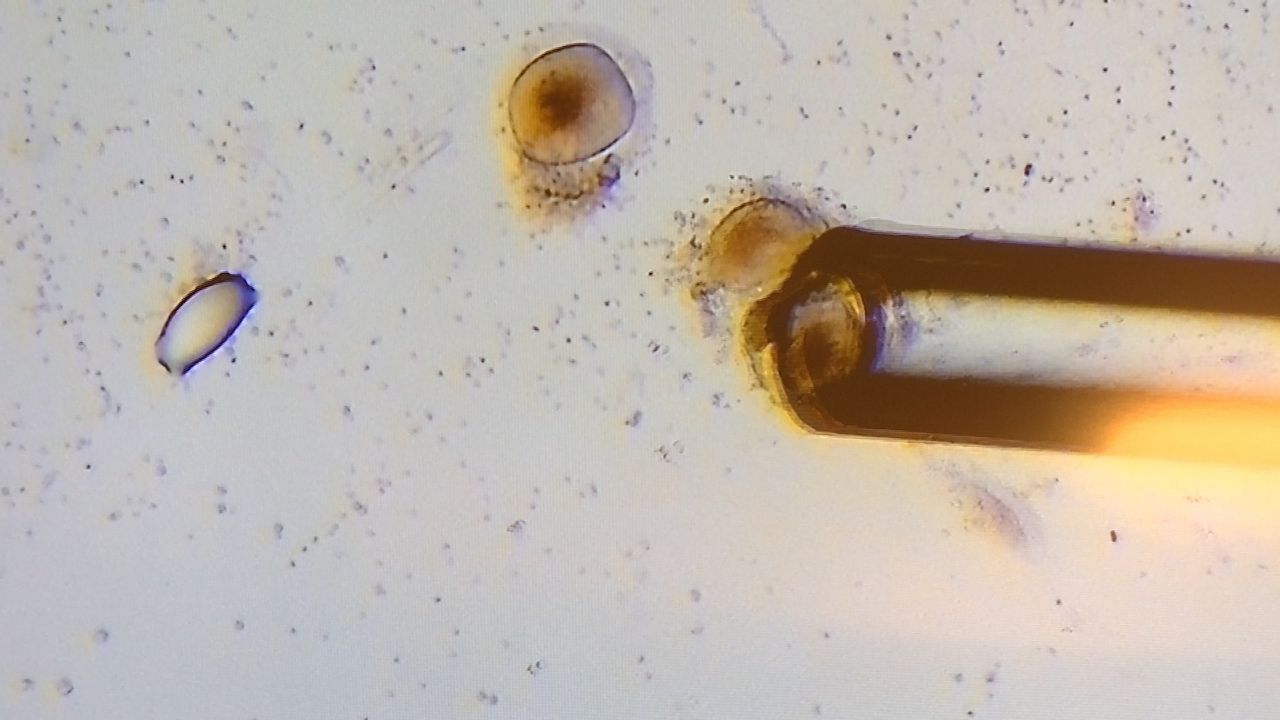

AK: “There is not. An egg is a single cell. And so we haven't figured out a way to test a single cell and figure out the quality of that cell and not destroy it in the meantime. So we could test quality, but it would ruin the egg that we're looking at.”

EB: Is there work underway to try and find a biomarker in the blood that points to egg quality?

AK:“I think we have some pretty decent tests of quantity. So, we've got AMH. There's another test called FSH, which is short for follicle stimulating hormone. It's more of an indirect marker of egg count. You can also do an ultrasound and actually count the number of eggs in the ovary. It's sort of a blunt technique, but it also works well, especially when you combine them. So, I'd say, we're better at assessing quantity than we are at quality. Age is our tool right now, but people are working on tests of quality as well. People are looking at things like how the egg looks, how the egg fertilizes, the different blood markers. There's nothing right now, but I think we'll get there someday. I would like to think so.”

EB: Women don't want to hear that... it feels as if we should be further along with technology than that.

AK: “No, it's not a nice thing to hear. But generally, age is the best test at this point. It’s frustrating for our patients and for us as clinicians that, that is the best we have to offer.”

EB: I thought it was more a genetic issue if a person has a higher percentage of egg cells with chromosomal abnormalities or, maybe, that it is due to poor diet or little exercise. What role do those factors play in preserving egg quality?

AK: “So, those are important. There are things that can make egg quality deteriorate even more rapidly. So, things like smoking and obesity. Unfortunately, we know obesity has effects on egg quality. Age as well as certain genetic conditions, certainly, can predispose you to an actual mutation in the chromosomes of an egg. But, those chromosomes will become abnormal over time anyway. If you think about what happens to your skin as you age. You've got young, healthy, non-DNA damaged skin when you're young, and then you get to your 40s or 50s or 60s, and you start to see age spots, and you start to see other things that are markers of cell aging. You see the same thing in eggs. We just can't see it like we can see things on our skin.

EB: As more women are waiting to start their families, is there anything more being done to support and help them plan?

AK: “We should be having these conversations with women earlier. We shouldn't be stopping at, ‘well, do you want children now?’ If the answer is ‘no,’ we move on.’ We should be having this conversation, which can be quite delicate and can take time, about what happens to fertility over time.”

EB: So, since the science isn’t there yet to preserve fertility, what are our options?

AK:“What I'm saying is, if fertility declines with age, you might want to think about starting a family earlier or at least keeping that in mind. The corollary is we don't make that easy for families because we don't necessarily provide paid maternity leave, time off of work, paternity leave, things like that. So, I think people wait until a point in their lives where they feel financially secure and ready, or maybe for a partner, and that, unfortunately, coincides with the time when fertility really starts to decline for some women.”

EB: Is more funding needed for research into reproductive health and fertility?

AK: “I do research and part of my research is around understanding the mechanisms that cause fertility decline and decline in egg quantity and quality. So, I will always be for more research and more funding. I think, in general, you will find that funding for women's health research is lacking compared to research in other areas. One of the ways to get at that is more conversations with legislators about the importance of these issues, more conversations in the general public, and more conversations in the media.”