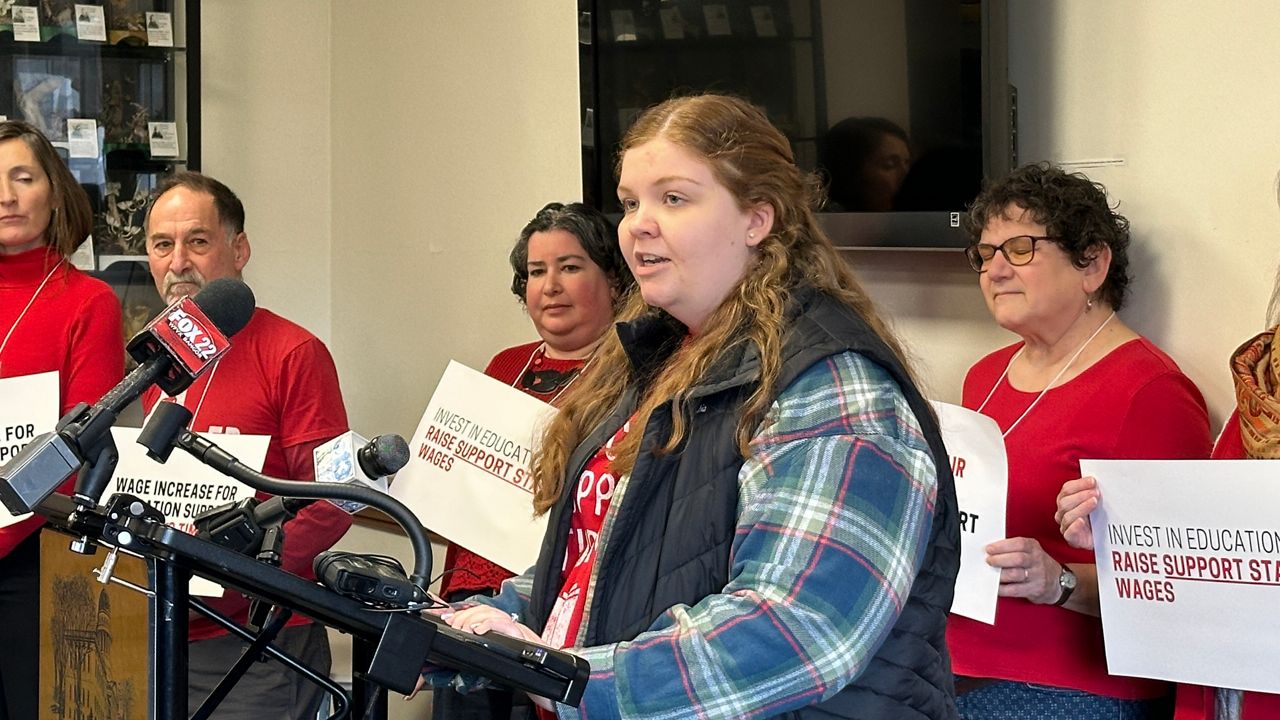

Maine is moving forward with a new testing system that it believes will best serve students, but might not meet all federal requirements, the state’s education chief told lawmakers Wednesday.

This spring, students in grades 3-8 and in one high school year will take math and reading tests so the state can continue to qualify for $55 million in federal funds, Education Commissioner Pender Makin said.

The state is expanding an existing test that has been used for years in Maine with the hope that it will meet federal requirements.

“We made a decision that essentially created less disruption, more class time, more information for teachers and we knew we would probably get our hand slapped on the other end,” she told members of the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee.

In February, the U.S. Department of Education threatened to pull $117,000 in federal funds from Maine because it does not believe its testing system meets standards.

Makin said she’s received assurances that the state will not lose funding and if it did, it would come from funds used to pay for administration, not monies that go to local schools.

Following the February notice, Makin said the state is working with its testing vendor to “bulk up” the system in a bid to meet federal requirements.

In a March letter to the federal education department, Makin said the state has made a “good faith” effort to meet requirements and that the proposed sanctions are “unreasonable.”

On Wednesday, she said tests used prior to the COVID-19 pandemic also did not meet federal guidelines. Nationally, fewer than one-third of states meet the standards.

DECLINING TEST SCORES AND ‘A CRISIS OF DISENGAGEMENT’

Committee members asked about declining test scores in Maine. In October, a national report card showed that the pandemic led to drops in reading scores for fourth and eighth graders in Maine and that eighth-grade math scores dropped to their lowest point since 1992.

Makin said the stress of the pandemic and a lack of school routine challenged many students — and continues to do so.

“We have a crisis of disengagement,” she said. “Students are not showing up. Students are showing up and are fully disengaged. Also, there’s so much now pulling on these kids.”

She said anxiety is high and many families are dealing with the housing crisis, substance use disorder and mental health issues. To address those needs, schools are trying to provide support services, such as free meals and behavior coaching, she said.

She also challenged the premise that test scores should be the primary metric on which student achievement is judged.

“At the end of the day, do we value high test scores above all else?” she said. “And if we do, there’s a guaranteed way I could get our test scores moving forward. What we do is we teach to the test. We guide the schools to use canned curriculum materials. We have them teach to the test and you will see those test scores skyrocket.”

She said in her conversations with parents, they are interested in creating students with a different skill set.

“Are you looking for sparking curiosity and having kids engaged in complex critical thinking around big projects?” she said. “There are many states where they are all out just like ‘get those scores.’ In general, when I have these conversations, people want a lot more for their kids here in our state.”