Teacher Kendrah Willey knows other educators who are living paycheck to paycheck, with many of them working second jobs to make ends meet.

When she graduated from the University of Maine last spring, she was one of only four students in the secondary education science program.

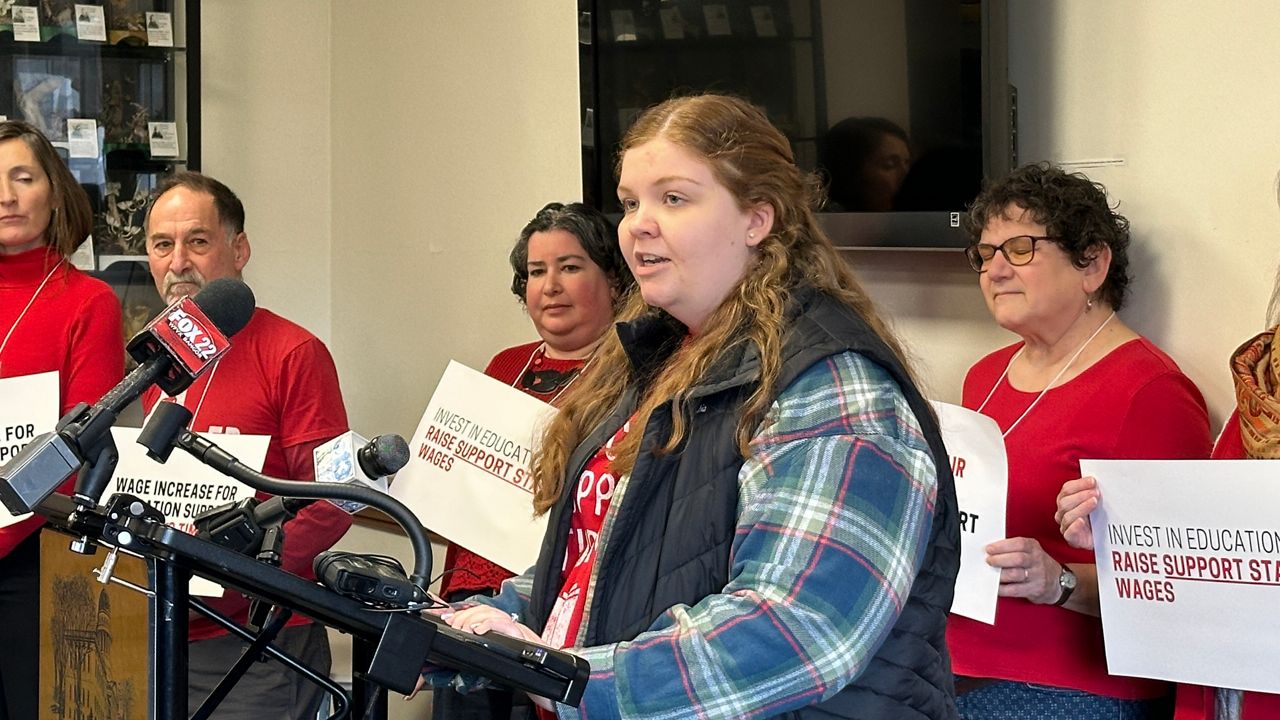

“I have classmates that are graduating with their education degrees, but choosing not to use them because they feel the amount of time, dedication and effort we put into teaching is not reflected in our pay,” she said Thursday at the State House. “I also have current colleagues that live paycheck to paycheck. They are not able to accrue any amount of savings because they are barely making enough to get by.”

Willey, who teaches in Regional School Unit 68 based in Dover-Foxcroft, was one of dozens of educators who came to the State House Thursday to lobby for two bills. One would raise the minimum starting teacher salary from $40,000 a year to $50,000 over four to five years.

That bill passed the House and Senate last year but has yet to be funded, said Rep. Michael Brennan (D-Portland), chairman of the Legislature’s Education Committee. He said he did not have a cost estimate, but that he hopes that because it would be phased in, it could be funded in the state budget.

The other bill would set pay for educational technicians at 150% of the state minimum wage, along with pay increases for other support staff such as custodians and bus drivers. That’s estimated to cost $14 million, with the state picking up about $7 million, Brennan said.

The Maine Education Association, which represents more than 23,000 teachers, support staff, and others, came to the State House armed with statistics to try to convince lawmakers to find the funds needed for both bills.

Since 2010, there’s been a 53% decline in the number of people entering educator training programs in Maine. The number of teachers who have quit has risen from 265 in the 2015-2016 school year to 533 in the 2022-2023 school year, according to the MEA.

And when it comes to pay, they argue that the state minimums have not kept up with inflation. For example, if the $30,000 minimum salary set in 2007 were tied to inflation, it would equal $43,767.

“Right now, in February, we’re more than halfway through the school year, a lot of districts still have huge numbers of vacancies they’ve been unable to fill and we need to do something about that,” said Grace Leavitt, a Spanish teacher from Cumberland on leave to serve as president of the union. “There’s a really urgent need for qualified teachers, qualified educational technicians, for all of our support professionals.”

That list includes cafeteria workers, bus drivers and custodians.

Lewiston ed tech Jim Handy said he helps students with math and writing and addresses a wide range of behavioral needs each day.

“I love my job as do my coworkers, but it’s very difficult to do this work,” he said. “The pay is low.”

He said pay for some is $20 an hour and that ed techs don’t get paid for 10 weeks over the summer. The low pay leads to difficulties with retention as well, with workers opting to leave for higher paying jobs in other districts when they get enough experience, he said.

Brennan said the bills to raise pay should be a priority for legislators this session. He and others have heard from many across the state that recruiting and retention continues to be a problem.

He also believes that fewer supports for students leave them feeling more anxious and depressed.

“There are two essential truths,” Brennan said. “One, teachers, ed techs, bus drivers, lunchroom workers, support staff, make a difference in schools. The second truth? They are not paid enough.”