HALEIWA, Hawaii — Peter Cole, who started riding big waves on Oahu’s North Shore in 1958, died at age 91. He was known for his longevity — he surfed until he was 76 years old, never using a leash despite surfing at Sunset Beach during the winter swells — and as a tireless conservation advocate.

He died on Feb. 5 in his Rocky Point home on the North Shore surrounded by his wife, Sally, and his son, also named Peter. The cause of death was heart failure. Cole is also survived by his sons Kaʻaina and Douglass and six grandchildren.

Cole grew up in Santa Monica, Calif., the son of Marie and Cornelius Cole II. He had an identical twin brother, Cornelius III (nicknamed Corny) and a younger brother, Schuyler (nicknamed Lucky). All three brothers loved surfing, and Lucky also moved to Rocky Point, where he still lives.

When he was born in 1930, Cole’s mother Marie didn’t know she was pregnant with twins. First, Corny was born, and then Peter came out, surprising his parents. Born early, the twins only weighed around three pounds. They shared a special bond growing up and even created their own secret language, according to his son, the younger Peter, who spoke with Spectrum News Hawaii.

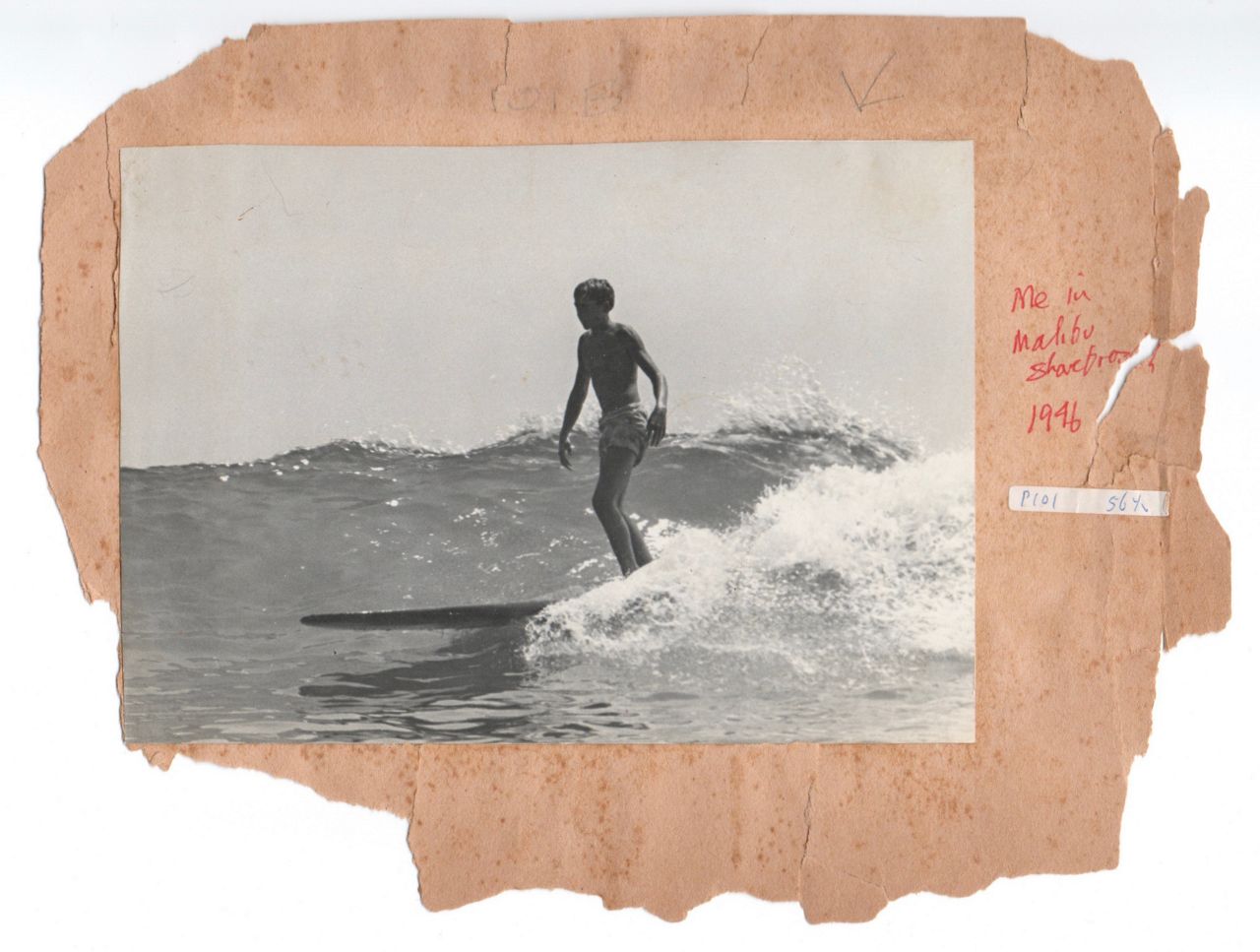

Cole started surfing when he was 15 in the summer of 1945 while living in Santa Monica. At first, he and his twin shared a redwood surfboard they found near a fence in Malibu that was left behind by a soldier who went to fight in World War II.

"The board was so heavy that Corny and I had to carry it to the water together," wrote Cole in a short essay that his son shared with Spectrum News Hawaii.

In 1953, Cole graduated from Stanford University, where he had been on the swim team.

“Swimming was a pretty big factor in his comfort in big waves … he always knew he could swim in,” the younger Peter said.

While in college, Cole spent his free time surfing at Santa Cruz, Calif.

In 1958, Cole arrived in Honolulu after getting hired at Punahou School as a math teacher. He said a major motivation for the move was Hawaii, which “had the very best surf in the world,” according to an interview he did in 1999 with Navy civilian and surf photographer Neal Miyake. He was also an assistant coach with Punahou’s swim and track team.

Cole told Miyake that in 1966 he left Punahou and got a civil service job as a systems analyst with the U.S. Pacific Command because teaching didn’t give him enough time to surf.

Still, he had a tremendous impact on many of his students. One student was Pipeline tuberider Gerry Lopez, who wrote on Instagram that Cole was his algebra teacher in 9th grade, describing him as “a great teacher.” He remembered one time when Cole arrived a few minutes late to class with wet hair and sand still on his neck, having just come back from a surf session. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, the two would surf together at Pipeline and Sunset.

“Peter was a sweet, kind, thoughtful man, always generous with his time and aloha to friends and strangers,” Lopez wrote.

His first year living on Oahu, Cole won the 1958 Makaha International Surfing Championships.

“The best surfers from all over the country — maybe the world even — would come to Hawaii for this and it was considered almost the equivalent of being a world champion, because you didn't have a world tour,” said the younger Peter.

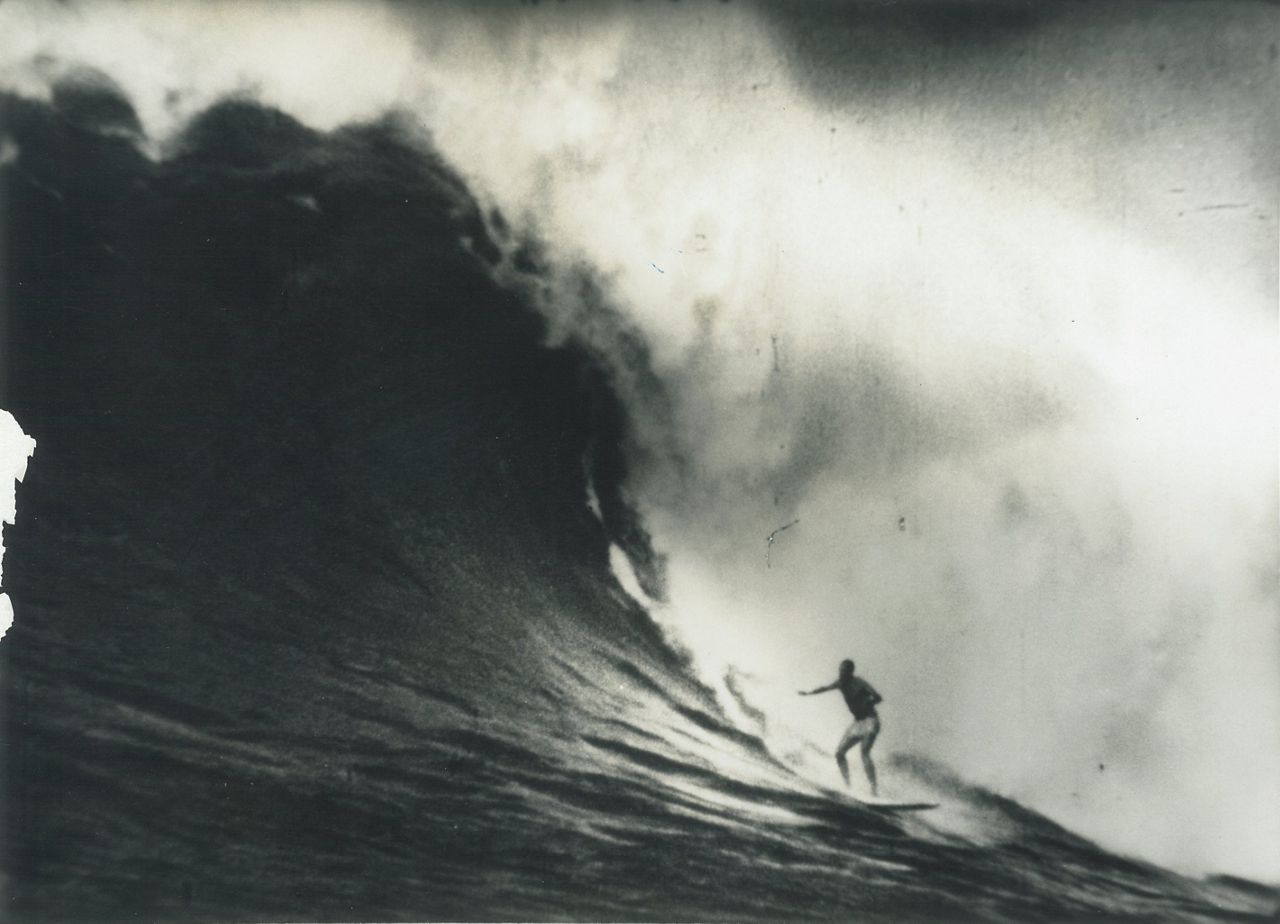

Miyake, the Navy civilian, told Spectrum News Hawaii that he was “star struck” when he interviewed Cole. “He was one of the pioneers from the North Shore and was known for his big wave bravado,” said Miyake. “When we talked surf his eyes just sparkled.”

During their interview, Cole told Miyake that Sunset was his favorite spot to surf because it was difficult, but never boring.

“It's always got variety, every wave is different from the previous one,” said Cole.

The younger Peter, who is an artist, surfer and father of two, recounted his father’s love for surfing Sunset: “It's so hard to predict what it's going to do, and there's an art to just lining up out there — picking a good one — that kept him interested the whole time.”

Cole was well-known for his conservation work on Oahu's North Shore, and he was the founding chair of the Surfrider Oahu chapter. He was determined to stop the commercialization of Shark’s Cove, the hotel expansion at Kawela and Kahuku Point, and he helped save Haleiwa Beach Park. He also worked to conserve Pupukea-Paumalu, the area that overlooks Pipeline and Sunset Beach, as developers wanted to turn it into a housing complex. Instead, community organizers raised funds in 2007 to buy it and turned it into a 1,144-acre park reserve.

“Peter’s legacy in surfing and conservation will live on through the protected coastal and ocean areas that he fought so hard to conserve, and by those who are following in his footsteps to protect Oahu’s ocean, waves and beaches,” Surfrider said in an Instagram post.

Cole also narrated and appeared in many surf films, including "Barefoot Adventure" (1960), "Cavalcade of Surf" (1962), "Locked In!" (1964), "Stop the Wave, I Want to Get Off" (1965), "Surfari" (1967) "Surfing for Life" (1999).

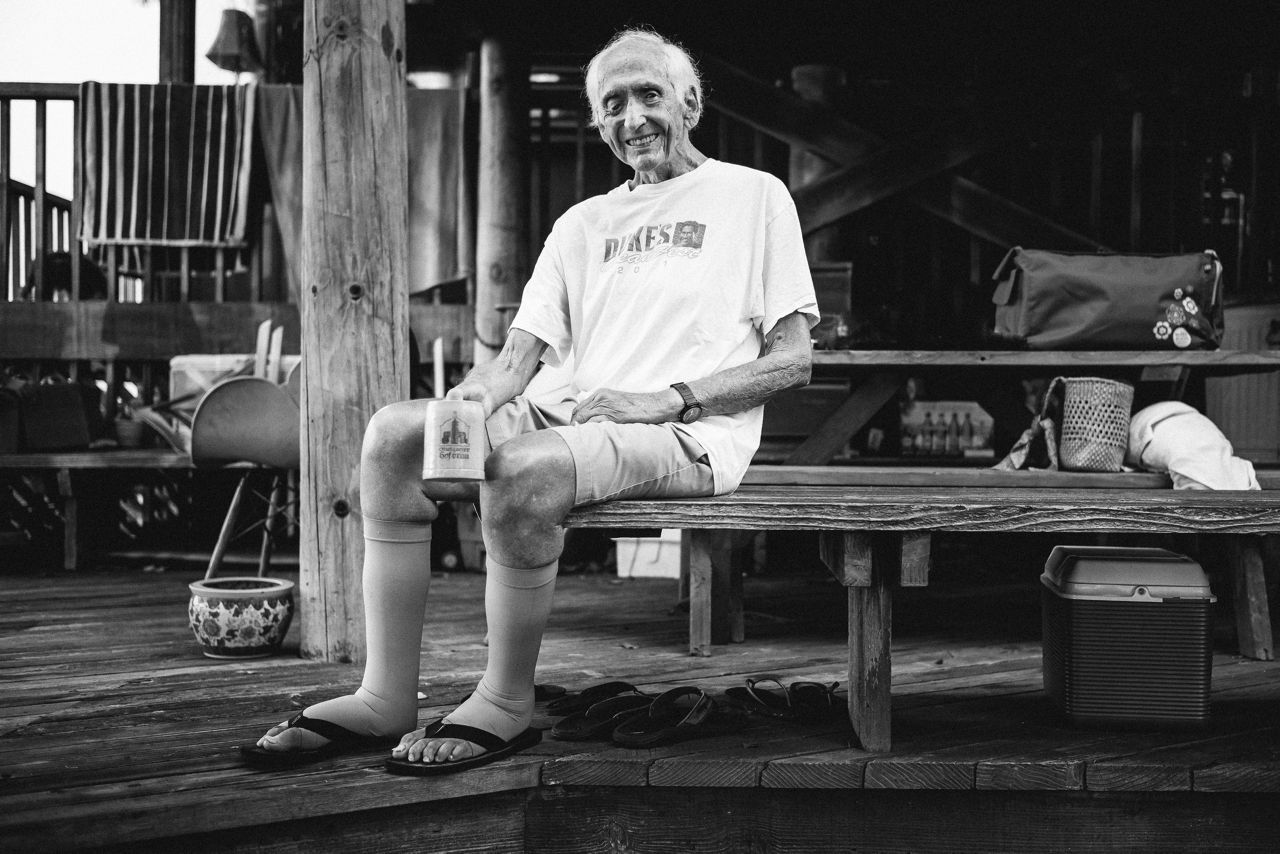

Rik Cederstrom surfed with Cole in the 1980s and 1990s, and described him in an interview with Spectrum News Hawaii as “the most stoked big wave surfer I ever met.”

He said that he first heard of Cole in the 1960s, so when he met him in the 1980s, it was like meeting a rock star. He said Cole was soft spoken and always friendly, and referred to him as a role model since he could surf great waves and be a great guy.

“The first time I saw him in the ‘80s, he was waxing up to paddle out on a day at Waimea,” said Cederstrom, who described the gigantic waves that day as making him shake with fear. “He was so casual. This was what he liked to do.”

He said Cole always wore a white t-shirt for sun protection, because “Hawaii never gets cold"; red shorts “so people could see him coming"; and used a yellow surfboard because it was “the easiest to see when you are swimming out to sea to retrieve it.”

Cederstrom remembered another time when they were both surfing at Sunset in the early 1990s, with waves as “big as houses.”

“A set is approaching, so critical that spray is blasting off the top,” said Cederstrom. “I'm paddling for the horizon as hard as I can. Quite apprehensive, you might say. Peter is paddling the opposite direction, much harder, driving to get into the place where he paddles down the face. He wanted that wave more than anything and they don't come easy. And he got it.”

Cole came up in big-wave surfing before leashes were used and became known for surfing without one even after they became commonplace.

“I refuse to use a leash. So I swim all the time,” said Cole in his interview with Miyake. He explained leashes made surfers go for quantity over quality, allowing them to catch waves that won’t work out because they don’t have to risk swimming after their boards.

“To me, it’s not how many waves you got; it’s how many good waves you got,” said Cole in the interview.

In 1972, Cole was surfing without a leash, as always, at Sunset with longtime friend Ricky Grigg, who was a big wave surfer and oceanography professor. They raced for their boards, and when Cole got to his board, he swam into the board’s fin.

“Nailed it with his eye,” said the younger Peter. As a result, he was blinded in his right eye.

In 2011, Cole was inducted into the Outrigger Duke Kahanamoku Foundation's Hawaii Waterman Hall of Fame.

He told his son, Peter, that the surfers of his time were all great watermen, knowing how to surf, swim and dive.

“The comfort in the ocean was different than … after the leash. There'll be more people getting in trouble if their leash broke that a guy like my dad would have to rescue,” said the younger Peter. “He thought it messed it up.”

“His whole life he never used a leash,” said Peter, even when he was surfing in his 70s.

Cole was respected for surfing into his later years, defying the odds of many surfers.

“I was especially intrigued by his perspective on longevity,” said Miyake. “He thought having other things in life like education and a career was essential to staying stoked on surfing. And acceptance that you will eventually get worse is important.”

In that interview with Miyake, Cole encouraged people to have families, “something that motivates you in your brain” and surfing.

“His passion and joy about surfing was so great,” said the younger Peter. “He'd be out there [at Sunset] on pretty hairy days into his 70s … waiting for the biggest set outside and people would be cheering him on when it came through because they loved him and wanted to see him get a good wave. … A lot of surfers felt like ‘I want to be doing that when I'm his age, that stoked about life and surfing.’”

The younger Peter said his father stopped surfing at age 76, after a cancer surgery that impacted his nerves and caused his arm to atrophy.

“Between my first wave in 1944 and last wave in 2006, I have witnessed many changes in the sport of surfing, and my ability as a surfer made a complete cycle,” wrote Cole in his short essay. “I started out a kook and ended up a kook.”

Until the end of his life, he kept getting in the water at Rocky Point to swim.

“He needed help just to walk down the beach. He wasn't so steady on his feet,” said the younger Peter, describing his father in his 90s. “Once he got in the water, he would get his normal stroke and swim well.”

“When I’d be helping him back up the beach, he’d be like ‘Look at this place. I'm so lucky.’” he added. “It is just that good feeling after being in the ocean.”

A paddle out this summer at Sunset is being planned to honor Peter Cole’s legacy and all are welcome to participate.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The original version of this story has been updated slightly to add more specificity to the year Cole began surfing the North Shore and to clarify which member of the family was being referred to in one sentence. (Feb. 22, 2022)