HONOLULU — Laura Beeman’s steely veneer cracked just one time on the sideline on senior night.

It came with 1 minute, 18 seconds to play, when four-year walk-on guard Hallie Birdsong scored a layup at home for the last time.

“That's what got me. I was fine until she scored and I started crying on the sidelines,” the Hawaii women’s basketball coach said with a smile after that March 8 contest against Cal State Northridge. “I don't know if I've ever cried on the sidelines during a game but that's the one that got me.”

Those sort of scoring opportunities may have been seldom for Birdsong over her career — three buckets converted, to be exact — but they were among the moments celebrated hardest by a program that has had no shortage of achievements to fete.

Big West regular-season champion UH (22-9) stumbled in the Big West tournament semifinals but plays on. It takes on host UNLV (25-7) in a Women’s National Invitation Tournament game at Cox Pavilion in Las Vegas at 3:30 p.m. Hawaii time Thursday.

UH is going for its first postseason victory in nine opportunities in the 13-year Beeman era.

Birdsong, as has been her role since she arrived out of Kalani High in 2021, helped the team prepare over the last few days by simulating opposing guards on the scout team.

“I know my role on this team, and although it might not be the most luxurious role ever, I take pride in it and making sure that my teammates are ready and that I challenge them day in and day out on the court,” the 5-foot-3 Birdsong said during senior week. “It really just is kind of the role that I've accepted here at UH and something that I enjoy — just trying to make this team and my teammates better.”

Birdsong missed her Kalani senior season of 2020-21 due to statewide shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, a perceived missed opportunity that would bring her to tears. Yet she made the Rainbow Wahine roster as a tryout, a jubilant moment for a family with strong UH ties. At that news, it was Norris Birdsong’s turn to cry.

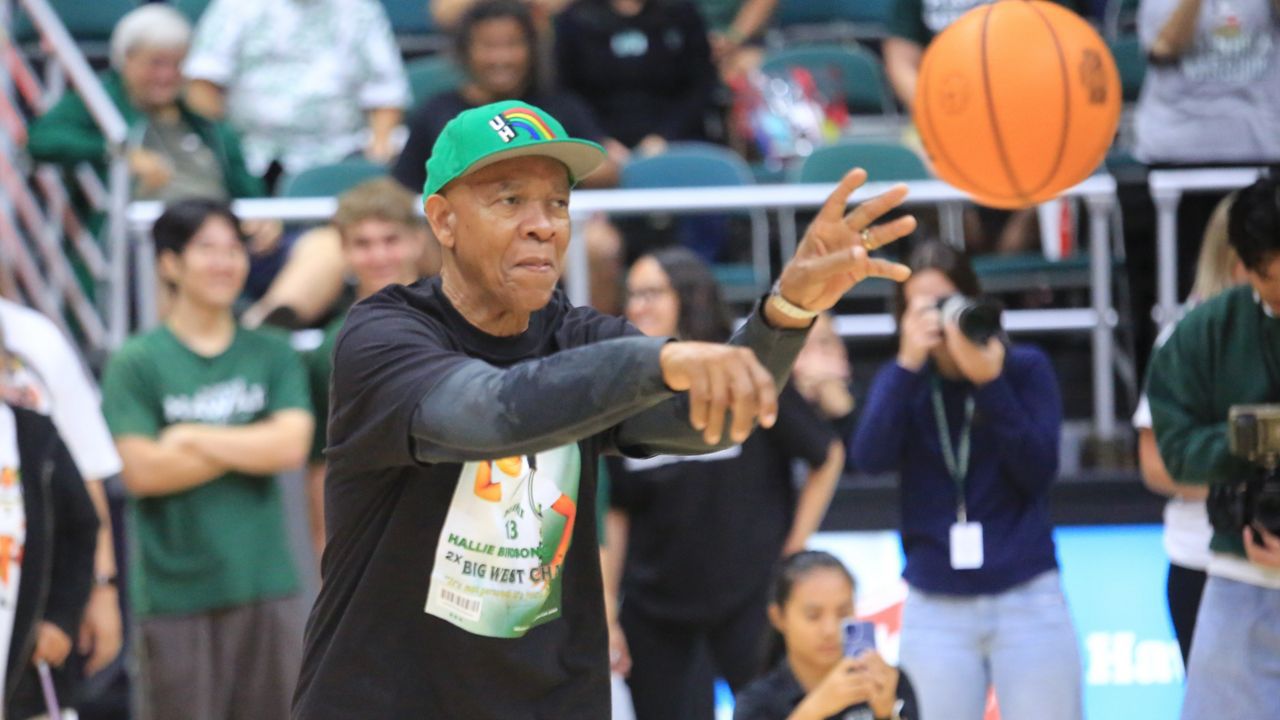

Basketball was always in Hallie Birdsong’s life — not a terribly surprising fact given that her uncle, Otis Birdsong, was a 12-year NBA veteran and four-time All-Star. She attended many of his skills camps growing up.

But her father, a former UH running back who had one of the first recorded touchdowns at Aloha Stadium when it opened in 1975, was just as involved in hoops as Otis at a young age growing up in Winter Haven, Fla.

It was Norris’ love for the game that drew her in. She began playing organized ball under his supervision with the Boys and Girls Club at Washington Middle School at age 7.

He trained his daughter as a shooting guard thinking she’d grow to 5 feet 9 or 5-10.

“I told her to shoot the drills that me and Otis did,” Birdsong said.

Otis Birdsong remains a notable veteran of the Brooklyn Nets (formerly New Jersey Nets) franchise as a 6-3 guard who scored over 12,000 points for his career at an 18.3 per-game average. He would regularly take in UH’s Big West road games in California, especially in the greater Los Angeles area, where he resides.

“Growing up, I always knew that my uncle played in the NBA, and that was always known throughout the family,” Hallie Birdsong said. It stood out to her that her uncle would focus on putting on camps in marginalized communities in their home state.

“For me, it was the way that he put on these clinics for free, and that the way that he handled himself, although he was a retired NBA player, is what stood out to me. It is kind of what I carry with myself as well, when it comes to when we do clinics and giving back to community and just seeing how important it is to other people.”

Norris Birdsong said his daughter did well at a camp for inner-city kids at West Palm Beach just before she joined UH.

“They rough man, but Hallie had to get rough with them,” he said.

“Then she came back and tried out for UH, and she brought that attitude to her tryouts. I think that really helped out, because she never, never played like that. She was playing like me and Otis, man, because we grew up in the hood. She was playing like she was on a mission, man. Even Otis told her.”

Together, the Birdsongs span a 50-year period of UH Athletics.

Norris and Otis were a year apart among a family of 12 children, but Norris ended up staying back a year in grade school to match Otis and make things easier on their widowed mother. They became inseparable.

Norris was set to go to Miami coming out of high school, he said, but didn’t have the grades. He went to Arizona Western College and prepared to enter the Division I ranks in 1975. He was about to go to Tennessee, when Larry Price swayed him at the last second with a flight out to the islands — one far longer than his young self could’ve imagined.

Birdsong led UH in rushing in 1975 with 715 yards on 165 carries (4.4 yards per carry) with six touchdowns, constantly marvels at the trappings of modern college athletics, like his daughter’s UH bobblehead.

“I say, ‘man, you doing more than me. You got rings. You got all this stuff,’” he said. “I say, Wow. You just took over. Man, I'm on the back seat.”

Birdsong was awarded financial aid during the spring semester of her junior season, a “fairy tale” moment of validation for her as she pursued her dream of playing Division I basketball in front of her family — Norris, mother Connie and younger brother Norris Jr., a guard at Kaiser High — who typically sat behind and to the right of the UH bench.

After his two-year UH career was done in 1976, Norris Birdsong went out for free-agent tryouts with a handful of NFL teams, most notably the New England Patriots. But an ill-timed, recurring leg injury repeatedly haunted him, he said, and he didn’t stick on a roster.

After that, he traveled frequently between Florida and Hawaii, and planted his flag in the islands for good in the mid-1990s, dismayed by a proliferation drugs and violence in his home neighborhood. He worked at the Navy Exchange and Home Depot, met Connie, a Kalihi native, and married her in 1999.

Connie urged him to go back and finish his UH undergraduate degree, which he attained in 2002 at age 48, in part to be an example for his four children.

Hallie Birdsong wants to be a doctor and plans to stay at UH to pursue her master’s.

“It truly is, was and continues to be a blessing for me to be able to live out my dream and play Division I basketball,” she said during senior week.

Beeman still considers the addition of Birdsong to have had great importance on the team beyond her scant career statistics.

“The sacrifice that Hallie Birdsong has given this program is probably greater than anybody I’ve coached in my life,” Beeman said.

Brian McInnis covers the state’s sports scene for Spectrum News Hawaii. He can be reached at brian.mcinnis@charter.com.

0320)