The most widespread marine pollutant in the ocean is plastic and its surface is the fastest growing habitat in the ocean, according to researchers at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

The good news is they have recently discovered that there are species of fungi from Hawaii’s nearshore environment that have the ability to degrade plastic — and some of them can be conditioned to do so faster.

“Plastic in the environment today is extremely long-lived, and is nearly impossible to degrade using existing technologies,” said Ronja Steinbach in a release. Steinbach led this research as a marine biology undergraduate student in the UH Manoa College of Natural Sciences.

“Our research highlights marine fungi as a promising and largely untapped group to investigate for new ways to recycle and remove plastic from nature. Very few people study fungi in the ocean, and we estimated that fewer than 1% of marine fungi are currently described,” Steinbach said.

Rather than break the cycle of making plastic, corporations continue manufacturing it because it’s cheap, strong and useful. Plastic is a problem, however, because it does not decompose. When exposed to sunlight, heat and physical force, it breaks into smaller microplastics.

Plastics are detrimental to marine ecosystems — dangerous chemicals such as phthalates and bisphenol A concentrate in the plastic; plastic can entrap and harm animals; plastic can be ingested and lead to malnutrition and starvation in marine animals because animals feel full and don’t eat actual food.

Plastic pollution is a critical issue in the state as ocean currents continually bring plastic waste from around the world to Hawaii shores. According to the release, the equivalent of nearly 625,000 garbage trucks of plastic enters the ocean each year so finding ways to degrade the compounds is critical.

Scientists have tested various microbes, including bacteria and terrestrial fungi for their ability to break down plastics with the hope that one day biotechnology could be deployed on a scale large enough to make a difference.

A team of researchers at the UH Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology focused on their large collection of fungi isolated from sand, seaweed, corals and sponges in Hawaii’s nearshore areas.

“Fungi possess a superpower for eating things that other organisms can’t digest (like wood or chitin), so we tested the fungi in our collection for their ability to digest plastic,” said Anthony Amend, Pacific Biosciences Research Center professor, who leads the lab where Steinbach and Syrena Whitner conducted the research. Whitner is co-author on the study and a marine biology graduate student.

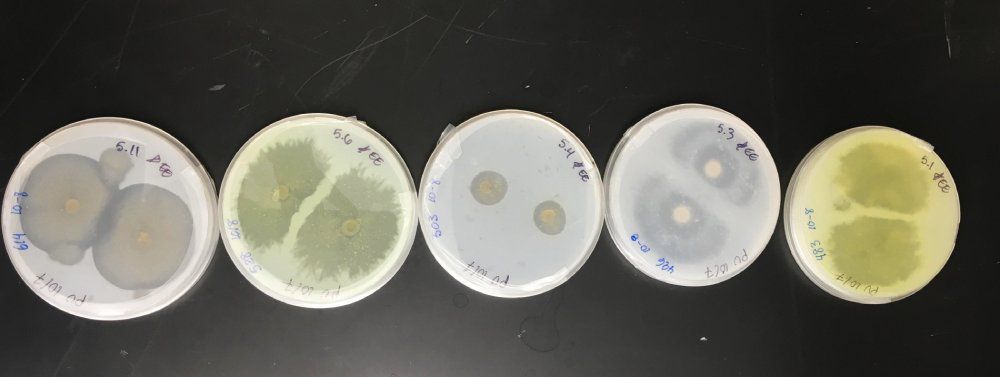

The team filled small dishes with polyurethane, a common plastic, often used in medical and industrial products such as foams, flexible materials and adhesives to measure whether — and how quickly — the fungi would consume plastic. They then took the fungi that grew the fastest and “experimentally evolved them” to see if the fungi could adapt to eating plastic faster and more efficiently over time with greater exposure to the polyurethane.

“We were shocked to find that more than 60% of the fungi we collected from the ocean had some ability to eat plastic and transform it into fungi,” said Steinbach. “We were also impressed to see how quickly fungi were able to adapt. It was very exciting to see that in just three months, a relatively short amount of time, some of the fungi were able to increase their feeding rates by as much as 15%.”

Their research is now expanding to see if these fungi and others can eat different types of plastic such as polyethylene and polyethylene terephthalate that are even harder to degrade, and even larger sources of marine pollution. In addition, the scientists are trying to understand how fungi are breaking down these compounds at cellular and molecular level.

Said Steinbach, “We hope to collaborate with engineers, chemists and oceanographers who can leverage these findings into actual solutions to clean up our beaches and oceans.”