HALEIWA, Hawaii — Patti Paniccia first started surfing in 1964, when she was 12 years old, after her family moved from Southern California to Waialua. In her early 20s, she started competing in amateur surf contests with the Hawaii Surfing Association.

A renaissance woman, Paniccia helped usher in women’s professional surfing in the 1970s, sued CNN for firing her for getting pregnant, wrote a book about women’s rights in the workplace and became a law professor who has taught courses on gender and employment discrimination.

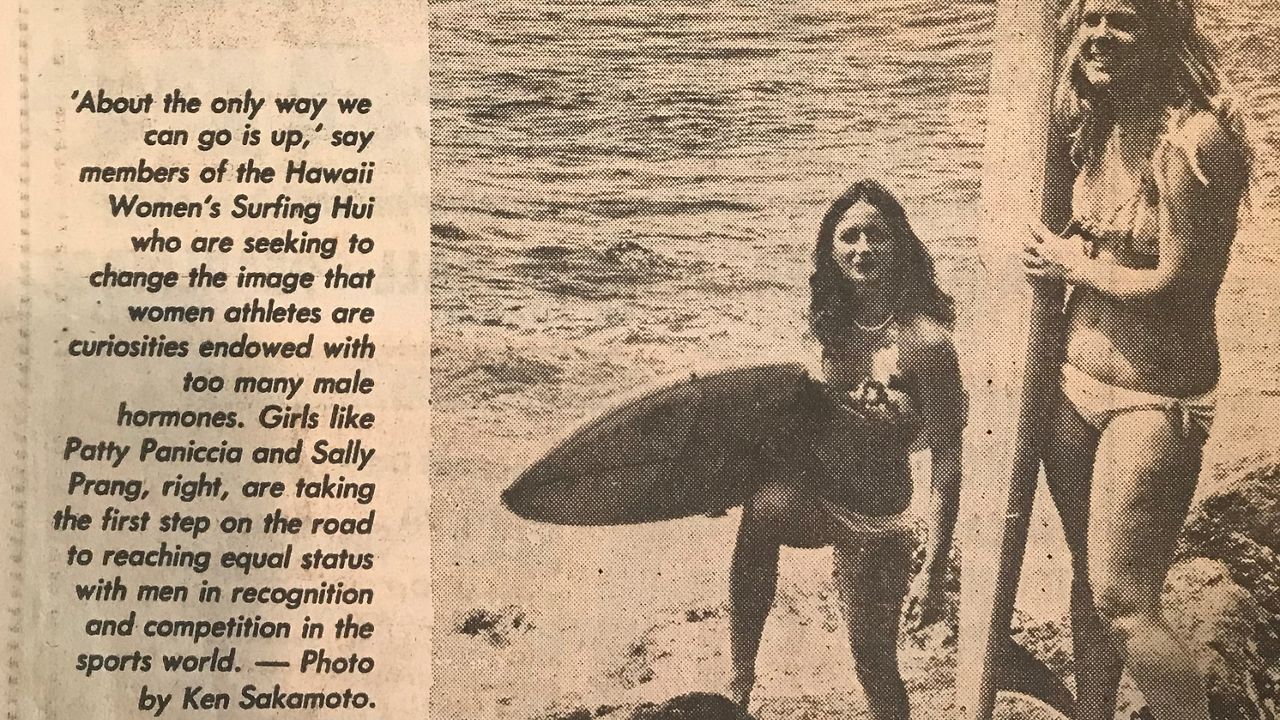

Women’s surfing in the early 1970s was radically different than it is now. Women weren’t included in surf competitions. It was challenging for women to find sponsorships. Women were rarely featured in surfing magazines. Sexist comments about women surfers were rampant.

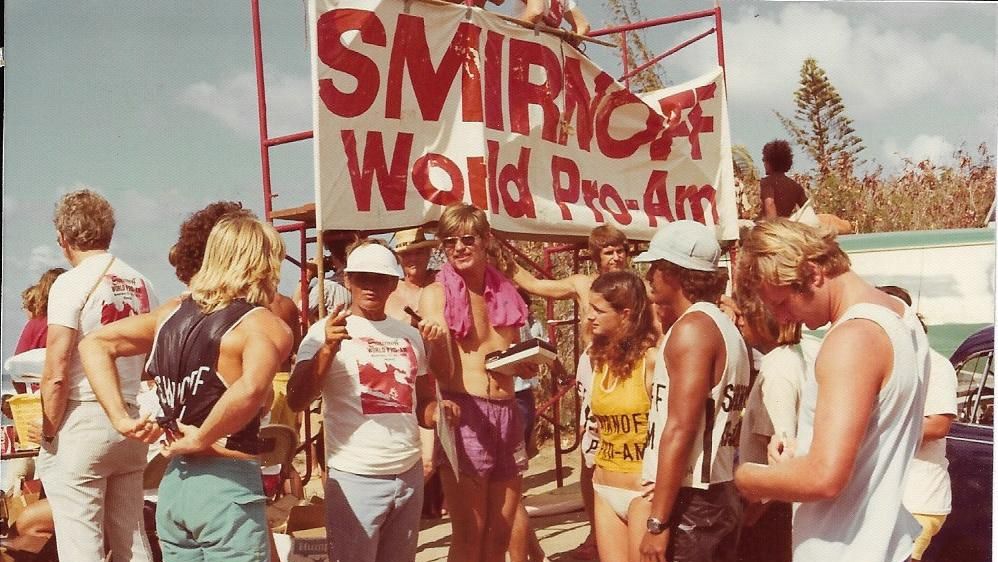

In 1975, Paniccia helped form the Hawaii Women’s Surfing Hui to support women surfers and combat the male chauvinism that pervaded the sport. The Hawaii Women’s Surfing Hui selected Paniccia to tell Fred Hemmings to include women in surf contests. She called him; they met for lunch and they argued about it and she eventually convinced him. Hemmings invited women to compete in the Smirnoff World Pro-Am Surfing Championships.

The following year, Paniccia, Hemmings and Randy Rarick started the first world surf tour, known as International Professional Surfing, which would later become the World Surf League.

Hemmings proposed the idea, which was modeled after a golf world tour. Rarick ran the men’s division. And 24-year-old Paniccia was the director of the women’s division.

“I made $100 a month, but that's because we were all broke,” said Paniccia. “Fred (Hemmings) was paying out of his pocket.”

Paniccia wrote letters to contest coordinators around the world, pitching the idea to create a tour linking surf contests in different countries.

“The first year for a women's and men's tour was 1976. And there were only six of us (women) on that tour,” said Paniccia.

They were Paniccia, Rell Sunn, Becky Benson, Lynne Boyer, Jericho Poppler and Claudia Kravitz. Paniccia said there wasn’t a stringent selection process, like the WSL’s Qualifying Series that is now in place. Instead, all the women surfers knew each other from attending contests and whoever could “muster up the sponsors and the money could go.”

Along the tour, which included six contests spread out across Hawaii, South Africa and Brazil, the women’s surf team was met with sexism from sponsors, sports journalists, spectators, contest coordinators and male surfers.

Candy Pants said they would sponsor them if the women surfers stood around in Waikiki wearing edible underwear. Reporters asked if they surfed naked. An article said they should go home to cook for their husbands — even though none of them were married. Contest coordinators planned a wet T-shirt contest, but the women declined to participate. The winning women surfers received one-tenth of the prize money that winning male surfers earned.

Despite this, Paniccia and the other women surfers on the tour stuck together and pushed forward.

“This was the time of Billie Jean King and women were just emerging and taking their rightful place in sports,” said Paniccia.

While working for the IPS and surfing, Paniccia was also slowly making her way through her undergraduate studies. After she earned a bachelor’s degree in communications from the University of Hawaii in 1977, she left Hawaii to attend Pepperdine Law School in California.

“I didn't stop surfing, but at that point, I stopped competing and I stopped running the IPS,” she said.

As for the progress made in surfing since the 1970s, Paniccia said she is extremely proud of young women surfers.

“These young women are just chargers,” said Paniccia.

However, she is surprised it took until 2019 to grant women equal pay in surfing.

“If I knew it was gonna take 50 years, I would have lost a little enthusiasm. I thought we’d fix it in a couple of years,” said Paniccia.

She also criticized the WSL, saying they also need to create equal opportunities for men and women on the Championship Tour. There are 17 women on the WSL’s Championship Tour compared with 34 men.

“So is that equal? No,” said Paniccia. “Why don’t they have the same number of openings for women than men?”

Since 1987, Paniccia has taught law at Pepperdine University, and she referenced how Title IX, a federal law, has been used to create equal opportunities for men and women to obtain sports scholarships at universities.

“The federal court said, of course, there's fewer women (in college sports) because interest and ability rarely developed in a vacuum,” said Paniccia. “They evolved from opportunity and experience. And until we start giving women the same opportunity and experience, they'll never get ahead.”

More than 50 years after Title IX was passed, Paniccia pointed out that women’s college basketball is filled with star athletes and has become extremely popular.

Spectrum News Hawaii asked WSL about the lack of gender parity in the number of competitors on the WSL’s Championship Tour.

"The WSL is committed to equality and the progression of women’s surfing,” a WSL spokesperson replied. “The WSL instituted equal prize money in 2019 and has hosted equal venues on the Championship Tour and Challenger Series since 2022, as well as introduced the first women’s CT competition at Pipe in 2021, but there is still more work to be done. Working in partnership with our athletes, we’re creating pathways to ensure continued competitive progression, and we’re committed to our goal of having an equal number of women and men competing in our events in the future."

When asked why she was so invested in fighting against gender discrimination, Paniccia said, “It came to me. I didn’t seek it out. Every time I wanted to do something, I didn’t like the way society was set up for women.”

First, she encountered barriers as a pro surfer. Then she went to law school and only 15% of her class were women. And later she became a television reporter, where she experienced a double standard with strict beauty expectations for women that don’t apply to men.

Following law school, she wasn’t sure if practicing law was what she wanted to do, so she got a job as a television reporter, starting at the bottom rung at a Santa Barbara station in 1982. She had surfed big waves at Sunset Beach and felt she could do anything — and she excelled as a reporter. In 1989, she was hired to be a news correspondent for CNN’s Los Angeles bureau.

After taking maternity leave following the birth of her second daughter, 40-year-old Paniccia returned to work at CNN and was subsequently fired.

“There was nothing set up in the system for women to be in the workplace, so getting pregnant was an unacceptable thing,” said Paniccia.

In 1994, Paniccia filed a sex discrimination lawsuit against CNN. An out-of-court settlement was reached two years later and the amount of the settlement was never disclosed.

“I didn’t want to be the poster child for pregnancy discrimination lawsuits, but I was,” said Paniccia.

Her experience inspired her to publish a book in 2000, called the “Work Smarts for Women: Essential Sex Discrimination Survival Guide,” which was designed to be the resource she needed when she was fired by CNN.

After CNN, Paniccia worked as a freelance reporter and started consulting small businesses. She also arbitrated automobile manufacturer consumer cases for 15 years.

In 2018, Paniccia became a hearing officer for the Los Angeles County Employee Relations Commission. Last year, at age 71, Paniccia was appointed to be a commissioner. Along with two other commissioners, she reviews cases brought by unions that represent LA County employees for unfair practices.

She encourages women not to be scared to reinvent themselves. Paniccia said people often have multiple interests, and they are capable of bringing a passionate level of intensity to several of their interests at once.

“You're not too old to reinvent yourself. Nobody is. I just did,” said Paniccia. “It’s a matter of wondering what do you want and how do you get there?”

Along with all the twists and turns her life has taken, she has continued to pursue her original interest: catching waves.

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii. Email her at michelle.brodervandyke@charter.com.