On June 21, 2013, the mailbox belonging to Honolulu Police Chief Louis Kealoha and his wife, Katherine, the deputy prosecutor, disappeared. That singular event triggered a wave of legal and political ramifications that reverberate in Hawaii to this day. A family financial dispute turned into a frame job when the Kealohas accused Katherine’s uncle, Gerard Puana, of stealing the mailbox. Puana was later cleared and received a $2.85 million settlement from the City and County of Honolulu. However, the legal troubles for the Kealohas were only mounting. In 2019, the couple and two police officers were convicted of criminal conspiracy in what became one of the biggest corruption cases in Hawaii’s history. After a stunning fall from grace, the couple are now behind bars.

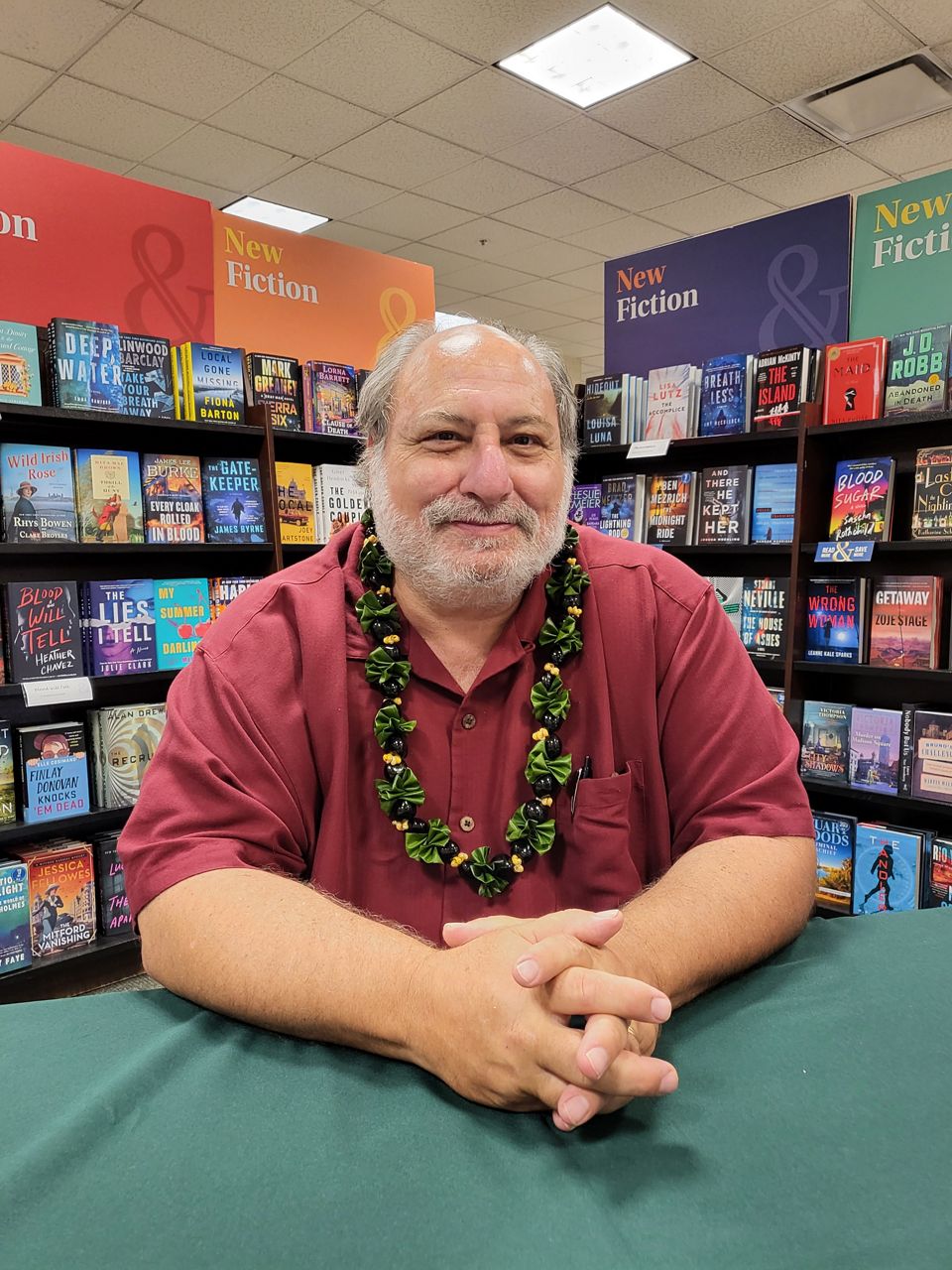

Spectrum News spoke with Alexander Silvert, a former federal public defender who represented Puana and uncovered evidence that led to a federal investigation that brought down the Kealohas. He is also the author of “The Mailbox Conspiracy,” a book that recounts this case.

Silvert: Well, there are two things really, and one’s a positive, and one’s kind of a negative. The positive is that after 10 years, this case still is having major ramifications on Hawaii politics and criminal cases. We still have two prosecutions that are still ongoing as an outgrowth of this case, and the grand jury is still going. So we might even have another indictment coming out of this. And it opened up the door. I don’t take credit for a lot of the new prosecutions of corruption that are going on with all kinds of officials, but it opened up the door to really allow that to happen and to be more acceptable. Whereas before, we really didn’t see a lot of these types of prosecution. So that’s a good thing.

But it’s also been really fascinating that 10 years later, we’re still doing this. The negative side, though, is that there hasn’t been a lot of structural change within our government, within the state or the city and county and particularly the city and county where they haven’t really changed what they were doing wrong before. They haven’t really examined what they were doing long before so they can make the changes they need to do. So there’s been this resistance still 10 years later. And part of what I see my job as the author of this book and as a lawyer who represented Gerard is to try to help force this change, to create the room for this change in our society, so we can get better.

Silvert: I do, and to do that, you have to do it two different ways. One is kind of like what the Foley Commission tried to do, which was suggest these new laws and these new regulations to control ethical behavior, campaign finance controls and so forth. Unfortunately, the minor reform measures were passed by the Legislature and the more serious ones that would have more meaningful impact didn’t get passed. But at least there was an effort, and at least we can build upon that and we can try next year. On the city and county side, there’s really been very little reform measures taken. So you know, one aspect of it is trying to create reform from within and the other aspect is we need to educate voters better.

Silvert: I think it’s done tremendous damage. And I’m really hopeful that the new Chief of Police (Joe) Logan will rectify this because he, to me, he’s the right person. He’s kind of a local person, but he’s kind of from the outside, and he’s coming from a very strong law enforcement background that isn’t from being a police officer. So I think he’s the right choice. And I’ve spoken to him several times, and I think he has the right mindset. He’s going to face stiff resistance from within the police department to this change. So I think it’s going to take a little time.

One of the things, unfortunately, that Louis Kealoha did — and a lot of people don’t understand this — is he de-professionalized the running of HPD. All police forces used to be beholden to the chief. If you're loyal to the chief, you can move up in rank, you can get a better position. This is the way it was from the 1880s to the 1940s. Then (came) this sense of a scientific approach to policing and professionalism, and you make a police force modernized. And, unfortunately, under Louis Kealoha, that just went away, and it went back to, 'If you’re loyal to me, you will get a promotion. If you’re disloyal to me, you will be sent to the nether regions of the police department.' So we’re recovering from that.

Silvert: Yes, we’ve stayed in contact. And, you know, he had that civil lawsuit against the city. So, I was going to be a witness in that, and so I was talking to him a lot about that case because he didn’t have any income. And he lost all that money. He had to sell that condo that he actually bought with his mother, and he moved into a studio apartment so he wasn’t in very good shape financially. And that created the pressure for him to settle a civil lawsuit for, I think, an amount that’s way too low. But as long as he’s happy with it, and as long as he and Florence's estate got what they felt they deserved, that’s fine. I felt it was way too low. Because part of the purpose of a civil lawsuit is not only to recoup for the victims some of the loss that they suffered, but it’s to punish the wrongdoers — in this case, the city and county so that they would put safeguards in place and won’t allow this to happen because the financial cost is too steep.

Silvert: I don’t. You know, Katherine claims in her latest filings that she told the prosecutors who the thief was. I get the impression that (she alleged) it’s not that the thief was someone she put up to it, but it was someone she’s learned while she’s in jail, who did it. And you know, I just I don’t think anybody believes that.

Silvert: Right. The Kealohas are back to 'We didn’t do anything. We didn’t set this up. We didn’t conspire to frame him.' Maybe they saw an opportunity to say it was him, and maybe they were wrong, but they weren’t doing anything nefarious. That’s where they are back to now that they’ve been convicted and punished. They can say anything they want. I really hope the public doesn’t fall for this, and I do think it re-victimizes the Puanas, this narrative. But on the national politics level, we’re learning to live with alternative facts. So I kind of know where the Kealohas are coming from. I don’t think we’ll ever learn (who was in the video). I’ve had theories of who it could be. I don’t have a name, but maybe they got a drug addict from her brother. Remember, he’s dealing with prescriptions, and maybe there’s some addict they got to do a favor for them. Maybe it’s a police officer who dressed up like this. We don’t know. And I don’t know if we’ll ever know. I’m pretty sure if the government knew, we would know. It would be front page news.

Silvert: Well, so under the law, you have the right to a direct appeal, which is you get convicted and then you appeal to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and that’s a matter of right. But the Kealohas gave that up when they pled guilty to the bank fraud. They had to sign the documents saying not only did they give up that right, but they also signed a document saying that all the facts of the mailbox conspiracy that were proven at trial were true. So they gave up all of their rights to a direct appeal. But now there’s something called indirect appeal, a claim of ineffectiveness, that your trial lawyer was ineffective, and that’s why you were convicted. It’s a very hard and high standard to meet. It’s not just a mistake was made. It has to be such a fundamental mistake that it affected the outcome of the trial. And it was so fundamental that any reasonable lawyer wouldn’t have made that mistake. So it’s a difficult threshold for any defendant to make. But you do have one year from the last action of your main case to take that appeal. So Katherine didn’t do that either. She had that right, but she didn’t do it.

So she comes back and claims that Earle Partington, her lawyer who she claims she hired to file that appeal, was himself ineffective for not filing the appeal. And if he wasn’t effective for not filing the appeal, then she should have the right to refile the ineffectiveness claim in a timely manner. That was shot down by Judge Seabright. And part of her problem is she’s making wild allegations all the time. When she’s filing her motions, I’ve had to read them sometimes three, four times to make sense out of them, because they’re rather bizarre and all over the place, which is interesting in itself, coming from a very high-level former prosecutor. They’re not legally sound. They’re misreading case law. And so they’ve been kind of bizarre for me.

Silvert: Nothing. Nothing truthful. So, first, I want to say, and very clearly, I haven’t read the book. So it’s a little unfair to criticize the book when you haven’t read it. I know that Louis Kealoha is not telling the truth now because in Puana's civil case against the city, Louis Kealoha was deposed under oath. And in that deposition, he claimed he was totally innocent. That he did nothing wrong. He didn’t frame them. And he wasn’t responsible for any crime whatsoever. He even was shown the document where he signed saying he was guilty. He even denied that he signed that document. So, he’s essentially now denying everything he was convicted of, everything he pled guilty to, and saying he’s completely innocent and wrongfully convicted. And he did this in a civil deposition under oath.

Now we have a book coming out, and from what the reporter said, he may not be claiming innocence, but he’s claiming he was essentially under the sway of his wife and he really didn’t do anything wrong. It was all her fault. God knows what else he’s saying in the book. And you know, quite honestly, I don’t think it’s truthful. I don’t think he was really confronted with the facts by the writer of the book. It’s a self-serving autobiography written by another person who’s a family friend. That’s all I can say about it at this point. I don’t think it’s going to show anything new that’s truthful. I think if people read it, they need to read it with, you know, glasses on and really ask the questions that I don’t think were asked of him. But again, I don’t think it’s fair to criticize the book until you’ve read it.

Silvert: Well, I’m hopeful. There has been some interest of late from some people, both on the television side and the movie side. It’s way too early in any of these things to know that anything’s gonna come of it. So we’ll see. I know that the public and a lot of people who have read the book are all saying that this has gotta be on Netflix, you know. And I agree. I think it would make such a great little series on Netflix, but that’s way out of my control. We’ll see if it happens. I would like to see it happen. It would be very interesting to see how the mainland people look at this.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview was edited for clarity and brevity. “The Mailbox Conspiracy: The Inside Story of the Greatest Corruption Case in Hawai’i History” was published in 2021 by Watermark Publishing. A revised, 2nd edition will be released in the coming months and will include new details on the case.