Though Mary Therese Hattori’s educational path, career, and family life have taken many twists and turns, one constant is that she has always used technology to empower Indigenous communities. Since 2020, Hattori has worked as the Director of the East-West Center’s Pacific Island Development Program.

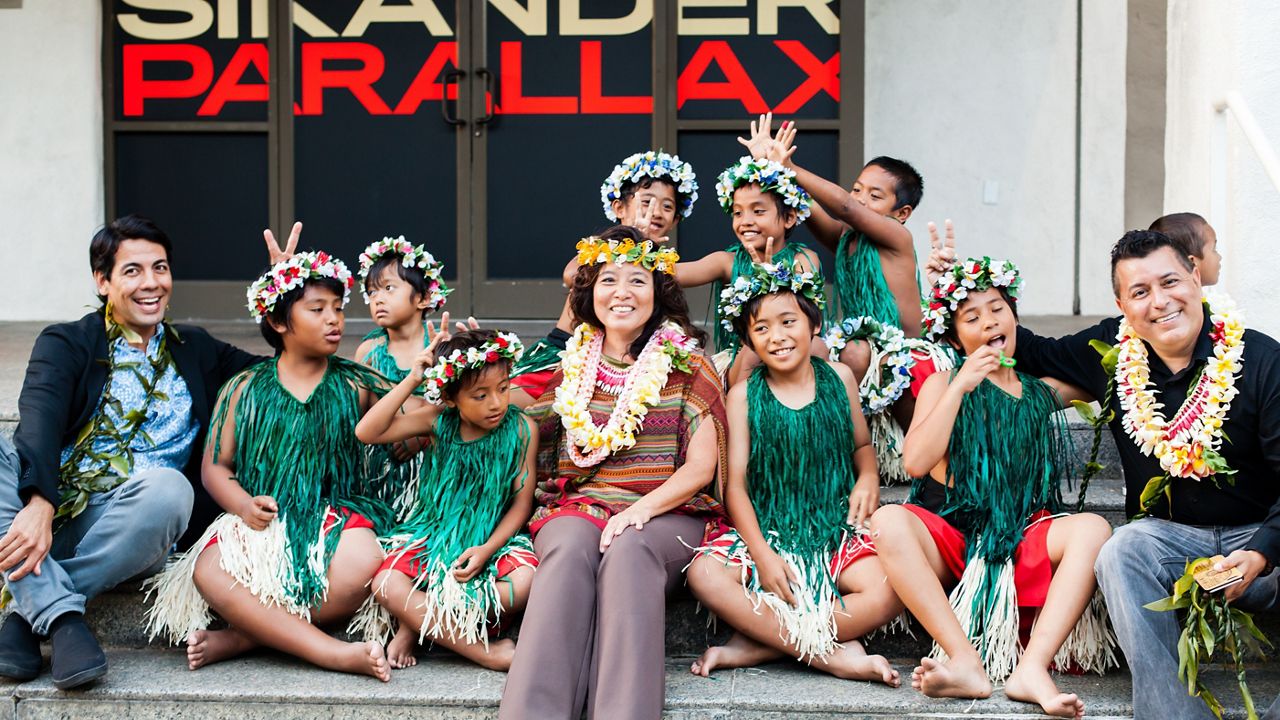

The Celebrate Micronesia Festival at the Bishop Museum is one of the major events that Hattori helps run as part of her EWC position. A diverse region in the Pacific Ocean, Micronesia includes the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas, and Guam. The festival, which began in 2014, celebrates the people and cultures from these island nations and territories.

As the pandemic was starting, the 57-year-old played an integral role in turning the Celebrate Micronesia Festival 2020 into a virtual event. The 7-hour event included virtual demonstrations, online discussions and more, and it can still be viewed on YouTube.

Hattori focused on creating an experience that upheld Micronesian values. At the opening of the festival, she compared a waʻa (canoe) to a computer.

“Just as waʻa carry life and carry us across the ocean, the computer carries us, our life, our spirit, our energy across the internet and connects us,” said Hattori.

In the following years, Hattori has transformed the festival into a hybrid event. This has given people in Micronesia, or Micronesians living on the U.S. mainland, the opportunity to speak on virtual panels or view the festival from afar.

“Communities are embracing technologies in ways that really empower Indigenous voices. Too often, we assume that Western technologies are bad for our people. But if you look at the way Indigenous peoples are using technology, they're actually using it to promote their own culture and sustain their own culture,” said Hattori.

Roots in Guam

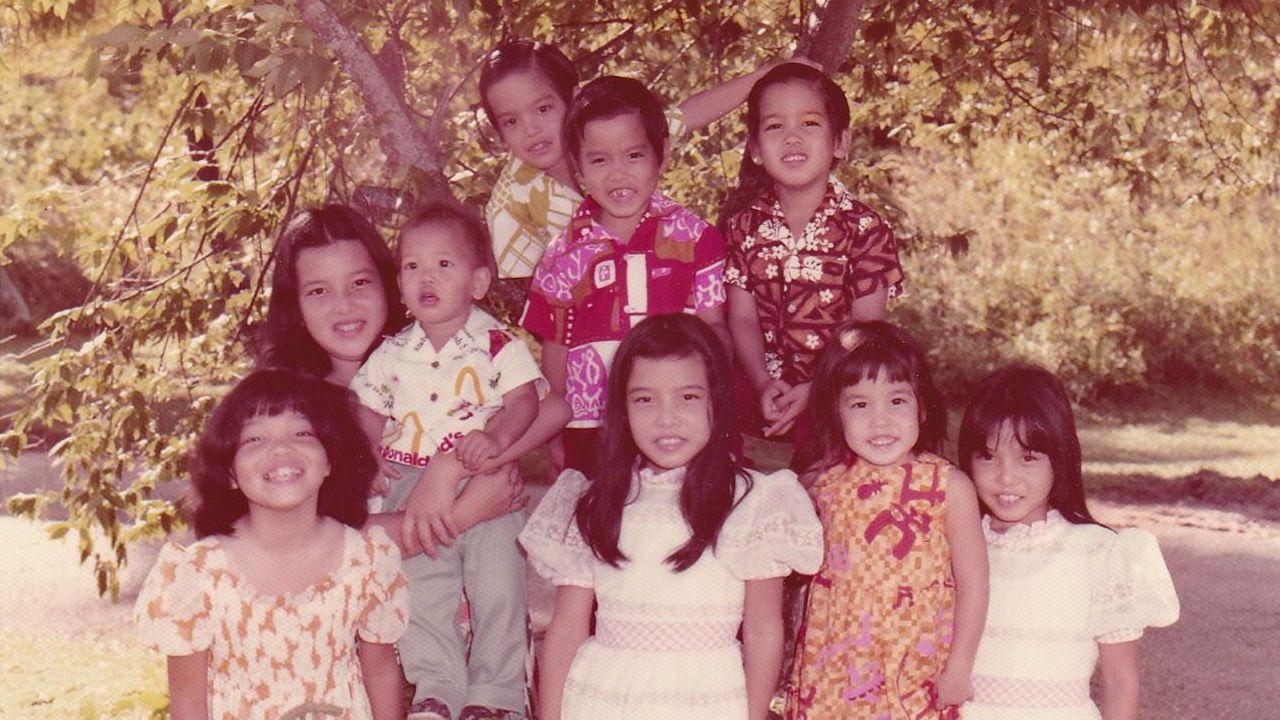

Hattori grew up on Guam, a U.S. territory in the Pacific Ocean. Her mother, Fermina Perez, is Chamoru from Guam and her father, Paul Hattori, is a Japanese American from Oahu. She is one of nine children and an identical twin.

“For Chamorus, it always starts with home and family,” said Hattori. “We always identify our clan, and my clan is Titang.”

A clan delineates village, relationships, and heritage, according to Hattori.

“Because my mother's Chamoru and Guam is a matrilineal society, it's important to place myself with her family. … Our roots are really based on her clan,” said Hattori.

When she was in high school, she fell in love with technology and was determined to pursue computer science. Her geophysicist father inspired her. He ran the Guam Magnetic Observatory, which is part of the Department of Interior’s U.S. Geological Survey. The Guam Magnetic Observatory sits on property owned by the U.S. Air Force and has two staff homes surrounded by the jungle. With little to do in the area, Hattori and her siblings spent hours in their father’s office, where there were many tools to monitor seismic activity.

“He was always into technology, and also was an early adopter of personal computers,” said Hattori.

While Hattori was in high school in the early 1980s, her father encouraged Hattori’s interest in computer programming. He helped establish a computer coding class at her all-girls school.

“I grew up with a Chamoru mother and then my father who is this nerd (and) scientist, but through his science, he really showed me my mother's beliefs: the land is animate,” said Hattori. “It was an interesting collection of both the Western science and Indigenous beliefs.”

Moving to Hawaii

In 1983, Hattori and her twin sister, Margaret Hattori-Uchima, moved to Oahu to attend the University of Hawaii at Manoa. They both chose UH Manoa because their parents said if they went to a college in the U.S. mainland that they wouldn’t be able to afford to fly home for the summer.

While Hattori had planned to become a computer science teacher, UH didn’t have a program that certified computer science teachers to work with high school students. In the end, she earned a bachelor’s of education in social studies, with a concentration in Pacific Islands history. While earning her degree, she also took engineering and computer science courses.

“By the time I graduated, there was a glut of social science teachers, so I couldn’t even get a (high school teaching) job,” said Hattori.

She wound up working at UH Manoa as a computer specialist in the early 1990s, while continuing her education. In 2014, Hattori earned a doctorate in education, writing her dissertation on culturally responsive educational technology.

While studying and starting her career, Hattori also became a wife and mother. In 1987, Hattori married her first husband, David Sasaki, a Japanese American from Hawaii. Ten years later, she gave birth to her son, Timothy Hattori Sasaki. The couple divorced in 2004, and Hattori married her current husband, William Talley, in 2007.

Starting a family grounded Hattori in Hawaii. She also stayed because she saw discrimination against Micronesians increasing and a need for educators who could help people in Hawaii understand Micronesians.

“Hawaii is not a harmonious melting pot. It's not a place where aloha exists for new migrants,” said Hattori.

From 2002 to 2015, Hattori was a professor at Kapiolani Community College. While there, she taught other teachers about how to support the Micronesian community and use technologies. She continued this work as the Outreach Director for UH Manoa’s Center for Pacific Island Studies and later as the Director of Chaminade University’s Center For Teaching and Learning.

“I've always had this connection between using technology to support Pacific Islanders, but also using technology to sustain our cultural practices,” said Hattori.

Facing discrimination

When Hattori arrived in Hawaii, she realized there were very few women in technology. Guam is a matrilineal society, and she grew up being taught women could do whatever they wanted.

“I never experienced sexism until I came to Hawaii. I never experienced racism until I came to Hawaii. So I was completely ignorant to the fact that when I walked into a meeting with technology people that I would be treated differently as a woman,” said Hattori.

She also experienced discrimination for being a Pacific Islander. In Guam, she spoke both English and Chamoru. When she arrived in Hawaii, she spoke with a Chamoru accent.

“I was unprepared for being bullied when I was in college … because of my accent.… I was told ‘this is America, speak English,’” said Hattori.

While navigating these prejudices was a challenge, she uses her experience to mentor young women in technology, educate professors on how to support multilingual learners and empower Pacific Islanders in all fields.

“In the United States, even in Hawaii, Pacific Islanders are underrepresented in leadership, … business ownership, (and) home ownership,” said Hattori. “One of the things I'm proud of is being in a position like this (at the East-West Center) and in other jobs that I've had to make spaces and opportunities for other Pacific Islanders to come forward.”

Hattori faced discrimination as a Chamoru, especially in the 1980s when she first arrived in Hawaii and the Micronesian community was small. She said other Micronesians, especially people from the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, now face even worse treatment. Social media, she said, allows hate speech to thrive and spread.

“I don't always feel safe if I go out in public in a Micronesian skirt,” said Hattori, referring to the colorful skirts often worn by Micronesian women.

However, at the annual Celebrate Micronesia Festival, almost everyone is wearing a Micronesian skirt. Hattori is proud to create this safe space and empower other Pacific Islanders.

Bringing her whole self into her work

Hattori is multifaceted: She is a computer scientist, educator, poet, community builder, daughter, twin, mom, wife, caregiver and Chamoru. While Hattori has many titles and roles, she always brings her whole self into everything she does.

“The Pacific way is to be holistic,” said Hattori. “There's a tendency to have silos or to be pigeonholed. And for us, it's not that way. … I love the ability to be who I am as a Pacific Islander and bring all of that into this job.”

Hattori spoke to Spectrum News Hawaii while at her office at the East-West Center, which is filled with books, art and crafts from Micronesia. She wore a necklace from the Pacific Islands Development Program's collection and a hair piece woven by a Native Hawaiian artist. She also wore a black sweater and dress as she is in a year-long mourning period, following the death of her twin sister.

In December, Hattori’s identical twin died suddenly while she was paddle boarding in Guam and got caught in a riptide. For the past seven years, she has been a caregiver for her husband following his diagnosis of early-onset dementia when he was 59.

“People see the successful side but don’t always understand the personal challenges,” Hattori said while tearing up.

Since becoming a caregiver and losing her identical twin sister, Hattori has been forced to redefine herself. She is still a wife but no longer lives with her husband, as he is in an assisted living facility. She is a twin but no longer has a twin.

“I think people need to understand that these challenges are not signs of weakness. They’re not things to be ashamed of. My staff is aware of all of this because I want them to see there are times when I need to lean on them more,” she said.

Hattori describes her success as not giving in to the many moments when she wants to give up and finding joy in the everyday things that bring her meaning.

“This whole work-life balance thing is irrelevant for Pacific Islanders. We shouldn’t be made to feel bad about bringing so much of our life into the work or feeling like we have to separate life from work,” said Hattori. “We should use our personal relationships as strengths.”

She hopes other Micronesians will see her as both successful in her career and someone with personal struggles and know they can thrive too.

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii. Email her at michelle.brodervandyke@charter.com.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was updated to reflect accurate information about the necklace Hattori was wearing while speaking to Spectrum News Hawaii. (June 6, 2023)