This profile is the first in a series on women journalists in Hawaii.

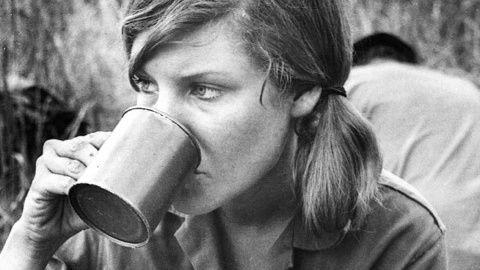

In 1966, Denby Fawcett was only 24 when she flew from Honolulu to Vietnam to report on the war. She was one of just a few women reporters who covered the Vietnam War.

“The one good thing about Vietnam, there was no censorship (for journalists) and you could go everywhere,” said Fawcett. “But then if you want to go out in a combat operation, you have to have the permission of the unit commander … And that was where I ran into trouble.”

Many commanders told her, “I can’t let you go. ‘You remind me of my daughter.’”

Finally, she got permission to join the 2nd Battalion, 4th Regiment, 3rd Marine Division.

“In the early days, it was a ceaseless struggle to be treated the same as a male reporter and when I finally was: a feeling of accomplishment,” said Fawcett.

The Marines were fighting on the border between North and South Vietnam. While with them, she witnessed the 1966 battle at the Rockpile, where at least 824 People's Army of Vietnam soldiers and 126 Marines were killed.

“It was the most intense time of my life, because every day you’d be covering a story that was so different — either frightening or exotic or fascinating,” said Fawcett.

Fawcett grew up in a house in Kahala, which was a rural beachfront community at the time. She attended Punahou School, graduating in 1959 — the same year that Hawaii became a state. She moved to New York City, graduating from Columbia University in 1964. After returning to the islands, she worked for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, the daily newspaper. She wrote for the women’s page, covering parties and gardening.

“It was a man’s world,” said Fawcett about the environment at the newspaper when she started. She said women were usually only offered “the lowest end of the paper’s jobs,” like working on the women’s page or in the mailroom.

In 1970, 46 women who worked at Newsweek in New York City brought a landmark lawsuit for sex discrimination. It set off a landslide of similar suits brought by women at Time Inc., Reader’s Digest, the New York Times, the Washington Post, NBC, and many more.

“So that helped open up things because it became illegal to put women in secondary jobs,” said Fawcett. “I was working before that, so it was not a very good atmosphere for women in news.”

Writing for the women’s page bored Fawcett, so she spent a lot of time reading the news, which fueled her desire to cover the Vietnam War.

“I think almost every young reporter wants to be on the top story of the day. You want to be where the action is,” said Fawcett.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin refused to send Fawcett to Vietnam, so she decided to go as a freelancer. Just before she left, Buck Buchwach, the managing editor for The Honolulu Advertiser, the competing daily newspaper, said he would send her.

“I think he saw that possibility, people would read about a woman reporter (in Vietnam),” said Fawcett. “So he offered me a job per article — he offered me $35 an article. And then I was only making $65 a week, so that would be a promotion. I wrote three articles (a week).”

When Fawcett first landed in Vietnam, she reported from the safe confines of Saigon, as her editor at the Honolulu Advertiser had insisted she stay there. She covered tourism in Vietnam, American missionaries who were translating the Bible into indigenous Vietnamese languages, and other feature stories. She stayed in Vietnam until Dec. 1967, during that time she joined with the Marines to cover combat battles, and she also reported on elections and the plight of Vietnamese civilians.

In 2002, Random House published a book called “War Torn: Stories of War from the Women Reporters Who Covered Vietnam,” in which Fawcett and eight other women reporters wrote about their time covering the Vietnam War.

“So many bad things happened in Vietnam. So many young lives needlessly lost. So many Vietnamese people (were) irreparably harmed. But in my own life, a small good that came of it was the fact I was there — that I saw it with my own eyes — which allowed me to be taken seriously for the rest of my life,” said Fawcett.

Over her long career, Fawcett has worked in print, television and digital journalism. Now 81, she is still reporting for a weekly column published by the Honolulu Civil Beat. For her column, she has written about the late Princess Abigail Kawananakoa, an African American man who settled in Waikiki after escaping enslavement in the early 19th century, the racist Massie case from 1931, homeless encampments on Diamond Head, the rise and fall in popularity of double red carnation leis, and most recently why school tracks are being closed to the public.

She said what ties all of her work together is a desire to share with readers stories they don’t know about and to open readers up to different perspectives.

Because she grew up and worked in Hawaii, she connects with a wide breadth of people on the islands who enjoy sharing their treasured memories with her. Fawcett also shares her own memories in her column, which range from how the princess kept horses in the old stables at Kapiolani Park to eating at Alex Drive In when carhops served the teriyaki burgers.

In 1970, Fawcett married a fellow journalist, the late Bob Jones, in Honolulu. The couple returned to Vietnam in 1972, with Jones covering the war as a NBC foreign correspondent and Fawcett freelancing. While in Saigon, she gave birth to their daughter, Brett Jones, in 1973. Fawcett took time off to focus on raising her daughter, but went back to work in 1987 as a reporter for KITV.

Tv reporting made her a better writer, forcing her to be more succinct and use active verbs.

“Verbs propel a story when it’s short,” said Fawcett.

While she loved TV reporting, she didn’t like that women reporters faced double standards, as they “have to dress nicely,” said Fawcett. She said viewers would call the TV station to complain about what women reporters and anchors wore.

“They’re not going to focus on a man’s Aloha shirt, if they didn’t like the print,” said Fawcett.

One of her favorite stories from this time was when she covered an art theft at the Honolulu Academy of Arts (now the Honolulu Museum of Art). In 2006, a homeless man snatched $500,000 worth of Indian jewelry and mailed them to his mother for a Mother’s Day present.

“The cops couldn’t crack that case, so the museum hired a private detective who (disguised himself as) homeless and found the man,” said Fawcett.

Fawcett said a docent at the museum tipped her off to the story. Initially, museum officials didn’t want to tell her what happened because they were embarrassed by how easy it had been for the theft to take place, but she kept making phone calls, getting more information confirmed, and eventually they talked to her. However, they didn’t want her to photograph the stolen jewelry after it was recovered, so she snuck into the museum and got images before security chased her out.

She stopped working at the TV station in 2010, wanting to work on a book about Diamond Head.

“I thought if I didn't quit, I'd never write it. And I'd be sad when I was dying,” said Fawcett. “I thought (Hawaii) needed a serious book about Diamond Head, because it’s the center of everything.”

Her book — “Secrets of Diamond Head: A History and Trail Guide” — explores geology, flora and fauna, the Hawaiian people, tourism, the military and development.

“In the '60s… they wanted to build hotels right around it,” said Fawcett.

She continues to report because she loves learning, and she loves being able to ask people questions and being able to hear their fascinating stories.

“It’s very good if you're an adventurous person, because it can also take you places that other people can't go,” said Fawcett. “It’s a great privilege, what we're allowed to do and then to think that you can help too.…; as a reporter, you can change things.”

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii. Email her at michelle.brodervandyke@charter.com.