HONOLULU — Some Manoa residents are upset that an affordable housing unit for residents 55 and older might be built in the forested area that abuts the Manoa Chinese Cemetery, but the president of the cemetery’s board says they are near bankruptcy and this would save them.

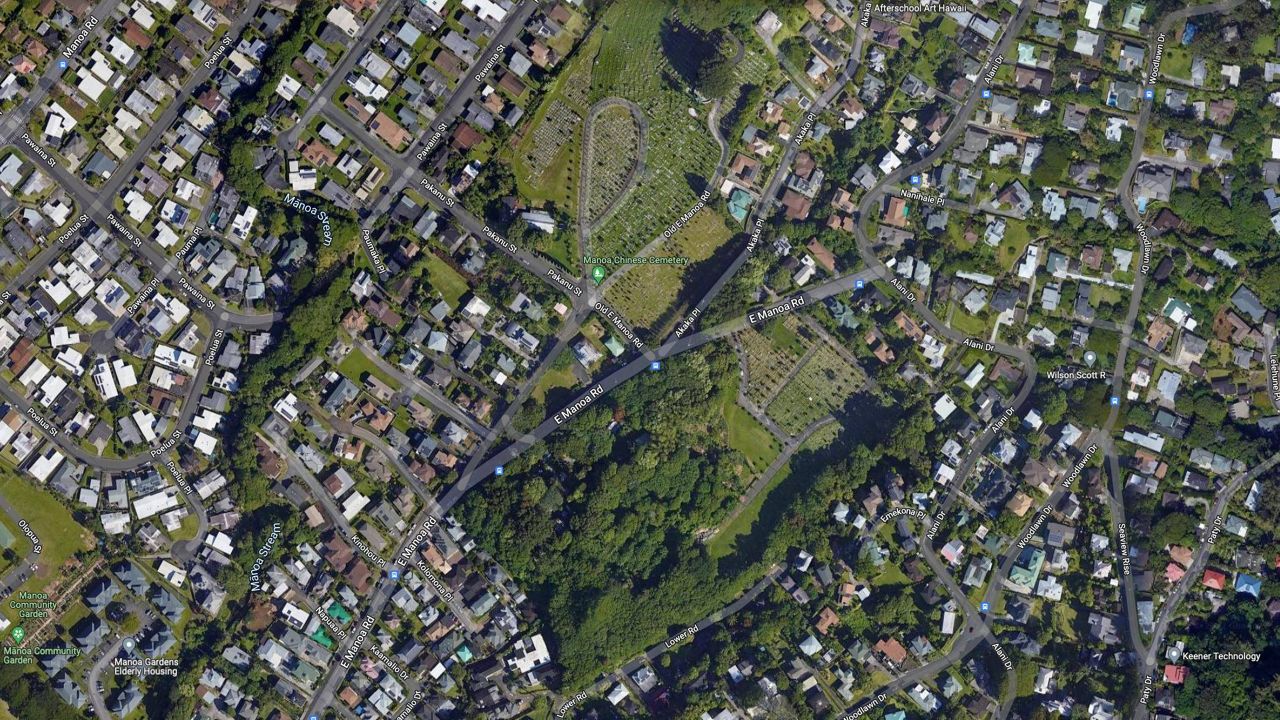

The project, called Manoa Banyan Court, would include 288 affordable housing units. It would be built on 10.5 acres of P-2 preservation land, which is owned by the nonprofit Lin Yee Chung Association, along East Manoa Road and includes four 3-story buildings, two common buildings and 185 parking stalls. In the triangle-shaped parcel at the fork of East Manoa Road and Old East Manoa Road, a community center would be constructed, which might include a wellness facility, a conference space, a heritage hall, possibly a school for traditional Chinese medicine, a cafe or store, and other buildings, according to project renderings.

The earliest LYCA would open Manoa Banyan Court would be November 2025.

The LYCA manages the Manoa Chinese Cemetery, which was established in 1851 after the original 31 members pooled their resources to buy the burial land, and now includes 27.5 acres.

“The Manoa Chinese Cemetery very much represents the history of our people in Hawaii, and that's why it needs to be protected and preserved as a historical and cultural gem,” said Charles Wong, the president of the Lin Yee Chung Association, in an interview with Spectrum News Hawaii on Thursday.

Wong said many cemeteries pay for maintenance costs through the sale of burial plots, but LYCA has very few left to sell.

“We will go bankrupt,” said Wong, who estimated that LYCA might only survive for another five years. “We have to move decisively to find a way … to save the Manoa Chinese Cemetery.”

Wong said the affordable housing project would provide a revenue stream to support the cemetery. He said it currently costs $20,000 a month to maintain the cemetery. That amount covers landscaping, property taxes, salaries, insurance and other expenses. Wong said the LYCA board of trustees are all volunteers and that professionally he is a property manager for McCully Garden Apartments.

“We're fighting for survival,” said Wong.

LYCA first started talking to Manoa community groups about the project in January. In February and March, representatives Wong and Weiland Tang, who is the chair of the development committee, attended the Manoa Neighborhood Board’s meetings.

The neighborhood board meetings have become contentious, with more than an hour of the March meeting devoted to eight community members questioning different aspects of the project. At the end of the March meeting, Manoa Neighborhood Board members decided their April meeting would mostly focus on the proposal for the affordable housing project.

Manoa Banyan Court would be built on P-2 general preservation land, which is owned by LYCA and defined by the City and County of Honolulu’s Land Use Ordinance as “lands designated urban by the state, but well-suited to the functions of providing visual relief and contrast to the city’s built environment or serving as outdoor space for the public’s use and enjoyment.” The green space currently provides contrast to the built environment, but is not accessible to the public. There are about a half dozen rental properties within the area that are tucked beneath tall trees.

By developing affordable housing under the 201H Hawaii Revised Statute, LYCA would be exempt from zoning restrictions. The 201H program is run by the Hawaii Housing Finance and Development Corporation and provides subsidized funding to developers of affordable housing projects and exemptions to certain planning and construction regulations, according to Brett Kurashige, who started an online petition to stop the housing project and spoke with Spectrum News Hawaii on Thursday. He said this was a major concern of his.

“That's how they would get around building on P-2 preservation zoned land,” said Kurashige.

“It would be potentially quite lucrative,” he added.

Wong described 201H as an important state program, because affordable housing is “critical” and “in short supply.”

“A lot of the Baby Boomer generation stands to become homeless because market rate rent keeps going up, up and up, and they're on a fixed income — pension plus Social Security,” said Wong.

He described the people who Manoa Banyan Court would serve as having too much money for government-assisted housing, but too little for the market rental rate in Hawaii.

He also stated that only half of the project would be funded by tax credits, while the rest would come from a mortgage and low-interest loans. For the first 15 years, LYCA might generate around $480,000 per year, which Wong said would help cover expenses. “We don’t have that kind of money right now.”

LYCA has not submitted paperwork for 201H approval yet. First, LYCA submitted its Draft Environmental Assessment to the Department of Permit and Planning. LYCA hopes to receive a “finding of no significant impact” in order to continue to the next steps in the process.

However, Kurashige, who lives on East Manoa Road just south of the green space that would become the Manoa Banyan Court, is troubled that LYCA was working on the Draft Environmental Assessment before they attended board meetings and he hopes LYCA will pause the project until the community has more time to provide input. The law requires that once a DEA is published by the state’s Office of Environmental Quality Control, the public has 30 days to comment.

“We oppose the way it was done under the radar to try and win approval without … broad community input and knowledge,” said Kurashige.

Kurashige said he is against the project because he thinks it will have too many units packed together for the mostly suburban Manoa community, increase traffic and decrease street parking, amplify noise, air and light pollution, remove valuable green space and exacerbate runoff during storms.

“(It is) one of the last green, forested open spaces in Manoa Valley. It’ll be bulldozed over — gone,” said Kurashige.

Kurashige is concerned that building the apartments and parking lot on top of the forested lands will make it an impermeable surface, increasing the possibility of flooding in the area, since green spaces absorb rain water.

Wong thinks these concerns are overblown and said the forested acreage is classified as Flood Zone X, which has a 0.2% chance of flooding.

As for the forest being removed, he said LYCA is working with arborists Steve and Ilana Nimz of Tree Solutions Hawaii, who will identify significant trees to preserve, and plant native Hawaiian and Chinese trees, such as lychee. He said currently, in much of the area, macaranga trees are growing, which are native to Asia and considered invasive in Hawaii.

Wong said what’s happening is a “not in my backyard” issue, also referred to as NIMBY, because many of the people who oppose the project live close to it. He said the neighborhood's opposition to the project showed a prejudice against people of a lower socio-economic group, referring to the people 55 and older that the affordable housing community would serve.

“We all agree for the need for elderly affordable rental housing — just not in my backyard,” said Wong.

Kurashige said he doesn’t want the fight to be seen as a NIMBY issue.

“It’s not fair to characterize us as NIMBY, because it implies that we’re just self-interested people,” said Kurashige. “It’s almost like we’re getting invaded. I look at what’s going on with Putin and Ukraine, and it’s like someone is invading Manoa Valley without our consent.”

Both Wong and Kurashige compared the Manoa Banyan Court project to Manoa Gardens Elderly Housing, an apartment complex for residents 62 years or older built in 1992. Although, they made the comparison from opposite perspectives. Wong said it was a project with more density, while Kurashige said Manoa Gardens was an example of a better way to do things.

According to Wong, Manoa Gardens is an 80-unit development built on 2.5 acres. He said if it was divided by acreage, then it would be about 32 units per acre, while he said Manoa Banyan Court would compromise 27.5 units per acre.

However, according to Gail Baron, a Manoa resident, Manoa Gardens is built on 4 acres, bringing the number of units/acre down to 19.2 units per acre. A search on the City & County of Honolulu Real Property Assessment Division's webpage confirmed that Manoa Gardens, located at 2721 Kaaipu Avenue, is on 4.168 acres.

Baron also sent Spectrum News Hawaii a 50-page proposal for Manoa Banyan Court that showed its four apartments would be built across 8 acres, with another 1.5 acres reserved for a community garden.

"With 288 units, Banyan Court density per acre would be 36 units per acre. That's almost double Manoa Gardens," said Baron. She added that she is "not for or against this project at this time."

Kurashige said he is not opposed to some type of affordable housing being built on the Manoa Chinese Cemetery’s property, but “in the proper scope and scale.”

“There’s probably a middle ground here. For example, Manoa has affordable senior housing. Manoa Gardens is a project that was done right,” said Kurashige. “If you look at it, it blends in with the community.”

Kurashige also suggested LYCA should pursue more lucrative cemetery options, such as building a crematorium on the property. Another idea he had was taking out caskets that were buried over 100 years ago and moving the remains to a memorial hall, freeing up space for new burials.

“Our understanding is that there's options that they have at their disposal if they choose to pursue it,” said Kurashige. “The ideal thing is … to have something that's supported by the broader community.”

Wong said alternatives have been considered, but that the LYCA is challenged because it doesn’t have much money. He also said the cemetery can’t be expanded to the 10.5-acre area where the affordable housing community is planned, because Woodland Ditch runs through the middle of it and the Department of Health prohibits burials within 200 feet of the waterway.

Rallies with about a dozen attendees were held on March 6 and March 11, and a third rally is planned for Saturday, March 26, at 10 am at the fork where East Manoa Road and Old East Manoa Road meet.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated to add in comments by Gail Baron. (March 29, 2022)

Michelle Broder Van Dyke covers the Hawaiian Islands for Spectrum News Hawaii.