TEXAS — Giving birth in Texas has become increasingly dangerous, according to a new report.

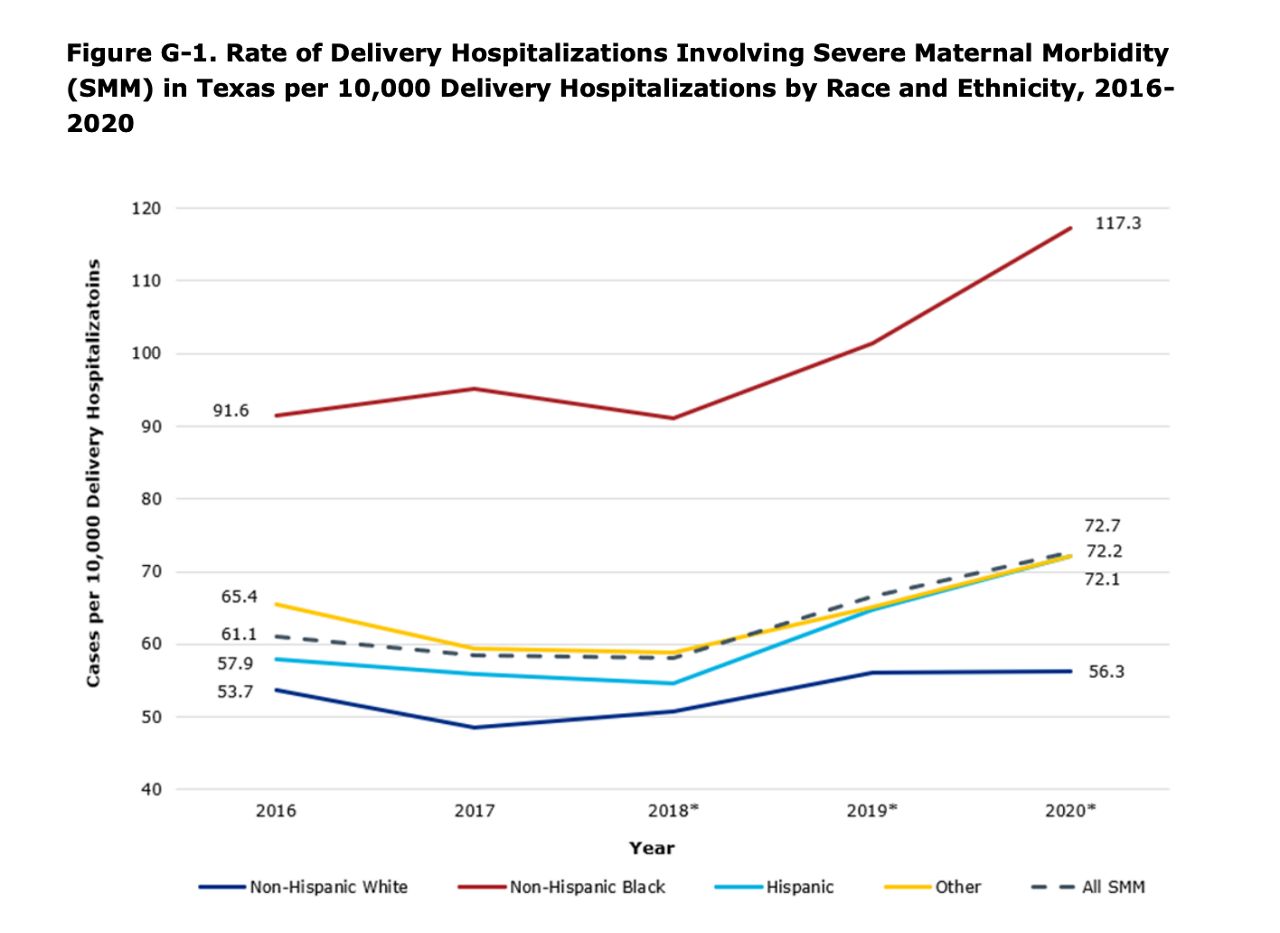

The CDC reports the national maternal morbidity rate in 2020 was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 deliveries. The 2020 rate in Texas was 72.7, and for Black women it's much higher.

What You Need To Know

- A preliminary report found an increase in maternal morbidity rates in Texas from 2016 to 2020

- The maternal morbidity rate for Black women was more than double that of white women

- Discrimination accounted for more than 12% of pregnancy-related deaths in Texas

- Out of all maternal morbidity cases in the report reviewed, 90% were preventable

The Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee preliminary data shows severe complications and deaths from pregnancy and childbirth have increased since 2016, especially for Black women. The maternal morbidity rate for Black women is more than double that of white women and far exceeds any other race.

Virginia Baldwin says her children are a miracle.

“It’s medically and scientifically impossible for these two to be here,” she said.

Before her 3-year-old daughter and 5-month-old son were born, she suffered two ruptured fallopian tubes. The second was so bad she needed surgery to remove it.

“I had been bleeding for weeks and I was in pain beyond describable,” Baldwin said.

She says she was repeatedly dismissed when she complained of severe pain. Doctors and nurses turned her away many times until the problem was too severe to ignore.

“If I hadn’t stayed on top of it, I would have died, both times because nobody listened to me, nobody believed me,” she said.

Baldwin’s story is not unique to Black women in Texas. Preliminary data from MMMRC shows disparities have not only persisted, they have gotten worse.

The maternal morbidity rates in Black women increased in 2016 to 2020, from 91.6 cases to 117.3 per 1000,000 deliveries. The overall 2020 average rate is 72.7 and the rate for white women, 56.3.

Nakenya Wilson is on the MMMRC and is a maternal health advocate.

“Black women were twice as likely to experience hemorrhage related issues, preeclampsia and sepsis,” Wilson said.

The Austin mother had three high-risk pregnancies, but she almost died from hemorrhaging after her second birth.

“I hemorrhaged, and they gave me mediation that could have killed me and my son was born not breathing,” she said.

While the report found the 2020 obstetric hemorrhage maternal morbidity rate was the lowest since 2017, it increased in Black women.

Studies show implicit bias in medicine leads to the belief Black people have a higher tolerance for pain. The review committee also found the data lack of diversity in health care, equity training, access to medical resources, healthy food options, and mental health services also contribute to these disparities.

“All of these different systems that were created in this country, the beginnings of them, the foundation of them, were not built in a way that was meant to equally care for Black Americans,” Wilson said.

Discrimination contributed to 12% of pregnancy-related deaths. Obesity and mental health were the top two factors. In all cases, the report found 90% were preventable.

The top recommendations from the MMMRC preliminary report include increasing access to comprehensive health services during and a year after pregnancy and engage Black communities and those that support them.

“I think overall, it seems oversimplified. For some, we have to value women’s life,” Wilson said.

Baldwin says she had to learn to advocate for herself, but she shouldn’t have to fight so hard to be heard.

“I advocated for myself because I didn’t want to ever experience anything like that again and I don’t want any other women to experience that again,” she said.

The MMMRC is still looking over the remaining data. One finding the committee will take a closer look at is the disproportionate impact of maternal morbidity associated with COVID-19 in Hispanic women.

From April to Dec. 2020: “Hispanic women represented only 48.3% of delivery hospitalizations during this time, but 70.1% of all delivery hospitalizations involving COVID-19-associated maternal morbidity.”

The final report has yet to be released, which legislators say is vital in order to create bills and policies to address the issue.