DALLAS — The Dallas Redistricting Commission selected a final map on Tuesday to move forward for consideration.

The commission narrowed the maps down to two choices, 17B and 41B, both of which got some tweaking before map 41B was approved 10-5 for advancement.

The map chosen is relatively similar to the current city council district map, and some residents are unhappy with the decision and say it won’t lead to the city’s progression.

Here's map 41B, which was approved by the Dallas Redistricting Commission after hours of deliberation Tuesday. (The second picture shows the painted map WITH current city council districts outlined in black.) The third picture highlights what the next steps are. @SpectrumNews1TX pic.twitter.com/u9ELnMSMSb

— Stacy Rickard - Spectrum News 1 (@stacyrickardTV) May 10, 2022

As it stands now, the Dallas council districts in the 2011 map are no longer balanced because of population growth. There needed to be a new map to balance out the council districts, but resident Christine Hopkins says the one chosen is not representative of the makeup of Dallas.

“It is a status quo map,” Hopkins said. “Dallas is unfortunately a city that loves the status quo. In my opinion, it’s a city by the wealthy for the wealthy.”

Hopkins lives in Oak Cliff, specifically in the Elmwood neighborhood. Oak Cliff is a historically Mexican American community, one which Hopkins says often feels neglected by the city of Dallas.

“I think that our Latino residents are going to continue to feel that the city government does not work for them, that there’s no interest in helping them with sidewalk repairs, lighting or anything until their property becomes valuable to gentrifiers, and until it becomes valuable to developers,” Hopkins said. “Who sits at the horseshoe is going to determine whether there continues to be a divide between investment in North Dallas, which is a lot greater than investment in South Dallas.”

The Redistricting Process was something Hopkins originally had hoped would provide more equity for her and her neighbors. She says commissioners stuck with the status quo and not give black and brown communities the voting power she believes they deserve, according to the data.

“According to the Census and Voting Age population data for the city of Dallas for the 2020 Census, we should be getting nine winnable, minority districts. We should be getting five of those districts where the Hispanic and Latino population is the majority and can control the results of the election. We are not getting that,” Hopkins said. “And with the map [41B], there are basically not going to be any more winnable minority districts than there were in 2011 and that there have been for the last 10 years, which is a complete violation, in my opinion, of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.”

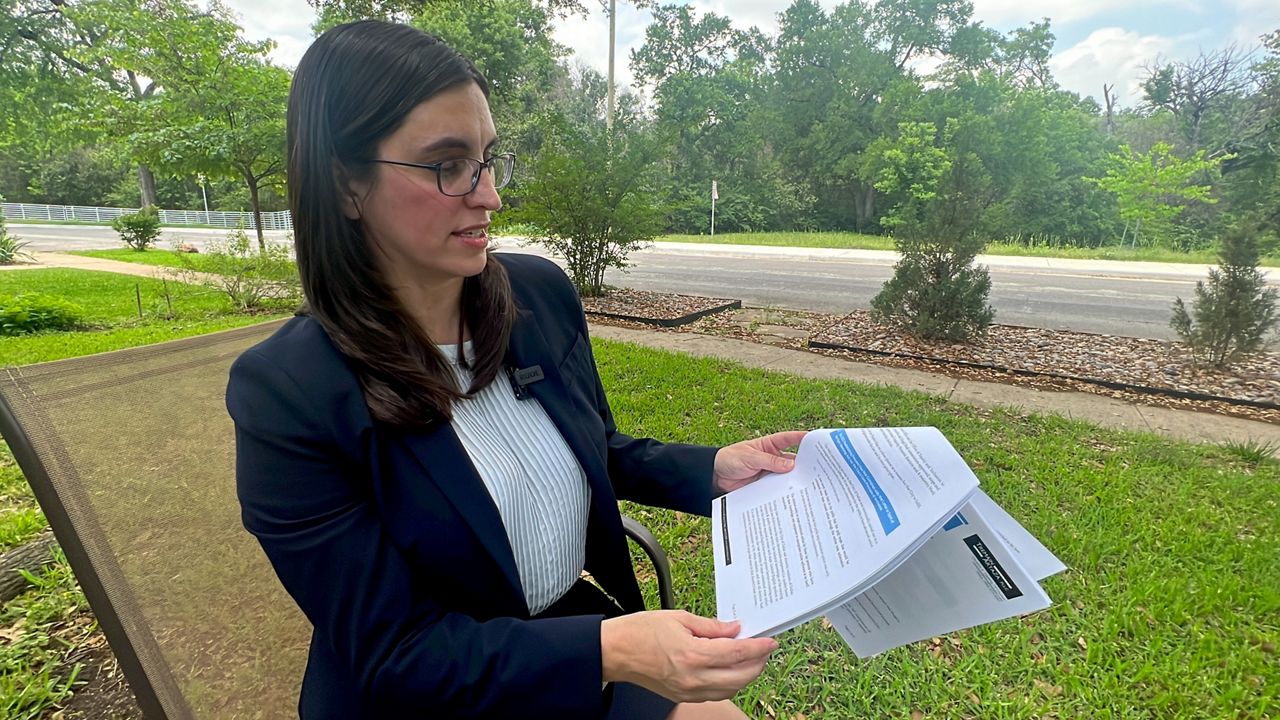

As an attorney, Hopkins now advises social justice organizations in the city to file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice. She’s already written one to the City of Dallas, City Attorney’s Office and the Office of Equity and Inclusion hoping communities of color get the voting power she says they’re entitled to. She believes there could be a lawsuit headed Dallas’s way.

“[41B] didn’t follow that letter or spirit of transparency or inclusion. If people feel like they can change an election and elect a representative that will represent them and change the historical neglect that’s gone on in their neighborhoods, they are going to get out and vote,” Hopkins said. “If they feel like it’s the status quo, and they’re going to continue to be ignored and industry is going to continue to be put in their backyard, why even bother voting? Because the city’s going to do what it’s going to do and they’re not going to get someone who represents their interests.”

Hopkins does not believe the map advanced by the commissioners helps to make Dallas a more diverse city.

“Unfortunately, the process has been completely broken and the math that will result will not give Hispanic, Latino, Black and African American communities the power, the true voting power that they deserve to have the representatives they want to represent them sitting at the horseshoe at the city of Dallas,” Hopkins said. “Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act says that you shall not deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, color or membership in a language minority group. So if you create a map that deliberately minimizes the voting strength of minority communities, then you violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.”

Hopkins also feels the Redistricting Process was done “backwards” and is advocating for change in the next one in 2031-2032.

“If you were interested enough or happened to hear about one of these public town halls — even though your neighborhood association wasn’t contacted, even though your church or school didn’t get out the word to you — if you happened to go to the meeting, all you could look at was 2020 Census results. That’s it. You didn’t see any proposed maps, you could not see what the maps would do to your neighborhood, to your district, to your voting power. That’s wrong,” Hopkins said. “Asking the public for input before the public even knows what’s going to happen with their neighborhood is wrong.”

Retired social studies teacher Bill Betzen drew several maps ahead of the narrowing down to the final few.

“I hope we have a very strong representation from the Hispanic community and the black community,” Betzen said.

He is passionate about the redistricting process in Dallas, and his goal was to create as many winnable minority districts as he says the updated Census data calls for.

“If we do [redistricting] well, we have better government and we need better government. We need a more responsive government. I’m a certified social studies teacher, you know, and so we need to be teaching more of that to our kids. We need to teach them redistricting. We need to be teaching them all of these nuances about our democracy, because that’s the only way our democracy is going to survive.”

Philip Kingston is a former city council member who, like Betzen and Hopkins, believes the new maps should enhance the power of the voters of color in Dallas.

“The big overarching reason for voting law in the United States since the 60s is to improve and enhance minority representation and that is the most important thing. It is in fact more important than anything else, geographic compactness that frankly, the Supreme Court no longer will take challenges based on geographic compactness apparently, so that’s not even an issue anymore. The issue is simply, can we have fair representation? Meaning an equal number of voters in each district, and how many how close can we get to making the council match the people that it represents?”

Kingston says where mapmakers go wrong is not understanding which communities are organized. Splitting up neighborhoods, he says, is an immediate problem if they are familiar with focusing all their power on a single council district.

“That’s the interesting thing because redistricting calls for a population balancing, assuming — as the founders assumed — that everybody would just go vote, right? And that’s not what happens,” Kingston said. “In fact, very few people vote in city elections. And the people who vote in city elections, frankly, are entitled to have their interest protected more than the people who do not.”

According to the Dallas City Code, the Redistricting Commission will now file its recommended plan with the mayor, who should present that plan to council at the next meeting. The city council should adopt the plan as submitted, or change and adopt it, within 45 days of getting it from the mayor. The code continues:

“Any modification or change to the plan must be made in open session at a city council meeting, with a written explanation of the need for the modification or change and a copy of the proposed map with the modification or change made available to the public 72 hours before a vote, and the proposed plan must be approved by a vote of three-fourths of the members of the city council. If final action is not taken by the city council within 45 days after the plan was presented to the mayor, then the recommended plan of the redistricting commission will become the final districting plan for the city,” Dallas City Code states.