TEXAS — While 16-year-old Bella Villarreal still managed to get all of her school assignments done after classes shifted online back in the spring, it doesn’t mean that she liked it.

“I didn’t enjoy it,” said Bella Villarreal. “I didn’t feel like I was getting the same level of education as I would have in school.”

Bella Villarreal, a student at San Antonio’s Independent School District’s Advanced Learning Academy at Fox Tech, said under normal circumstances she would prefer in-person instruction.

“A lot of my friends struggled with being productive because it’s harder to be motivated when you’re alone and there’s nobody to keep you accountable,” said Villarreal.

Mike Villarreal, Bella’s father and director of the Urban Education Institute at the University of Texas at San Antonio, figured there was a lot to be learned from the forced social experiment of transitioning kids from in-person learning to instruction completely online.

“Me and my team asked ourselves ‘what can we do to help our community?’” recalled Mike Villarreal.

As social scientists, their answer was to research how parents, teachers and students were all experiencing the sudden dramatic shift to distance learning.

Understanding that not all stakeholders may have access to the internet, Mike Villarreal’s team assembled more than two dozen UTSA students into a phone survey team. The team contacted students and parents in eight participating school districts across Bexar County.

“Over the course of two months they made over 20,000 phone calls,” said Mike Villarreal. “Ultimately we reached nearly 2,000 individuals asking them about their experience during this very traumatic time.”

While their study reaffirmed the existence of a digital divide, their research showed that surveyed school districts did remarkably well making sure students that didn’t have reliable internet access at home, got it.

“Nearly 95 percent of every family reached said they had some kind of computer device and they had access to internet,” said Mike Villarreal.

“We asked ‘Where did you get your computer device?’ And for some school districts, 35 percent of the families said we received our device from our school district.”

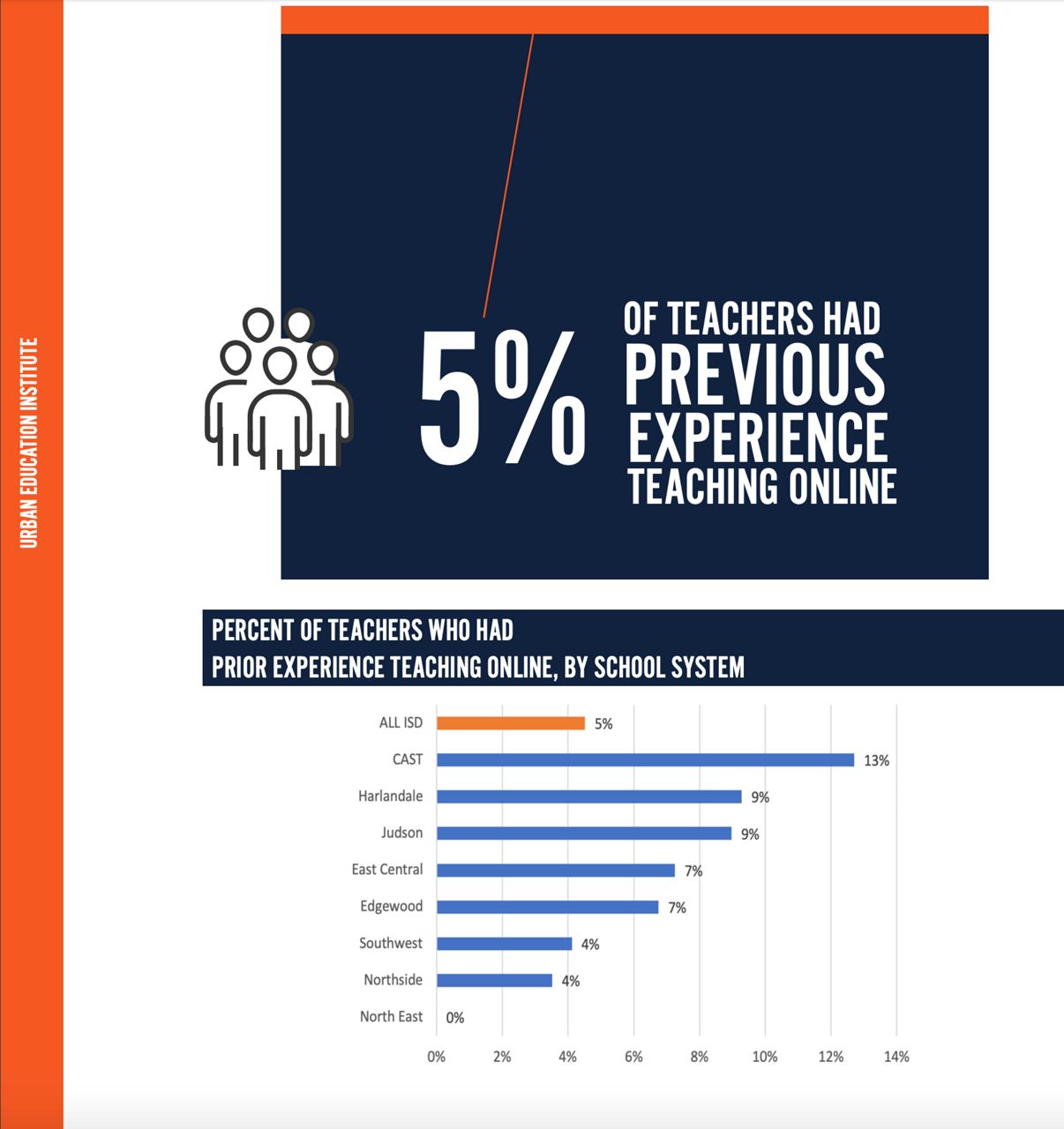

Despite teachers and students having the tools, utilizing the technology was a crash course for teachers. Only 5 percent reported having previous experience teaching online. And while the research found teachers were primarily able to adapt, and quickly, many teachers had to act not only as educators but as tech support for countless parents that didn’t know how or weren’t able to access the online interface.

While some students thrived in a remote learning setting, the study showed that most did not. 65 percent of responding teachers claimed their lessons were less engaging. 59 percent of teachers said their students were turning in assignments less often.

“Many students just didn’t show up, didn’t log in,” said Mike Villarreal. “That’s going to be something that is going to need to be addressed in the fall.”

Mike Villarreal is hopeful his team’s research will help school administrators better handle those challenges, as many plan to go back to school in just a few weeks, returning to an all-online education once again.