SAN ANTONIO — Tejano artist Veronique Medrano appreciates the people that paved the way for her.

The Rio Grande Valley native took a trip to the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University and admired the suit of legendary country star Freddy Fender (born Baldemar Garza Huerta).

“Look at the condition of that, you still see the sweat stains,” Medrano says.

Fender was born in San Benito, Texas, and used to work in the fields when he was 10 years old.

He sang the timeless hits “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” and “Before the Next Tear Drop Falls.” He’s had major success on the Billboard charts with four number-one country songs, two number-one country albums, and eight top-10 country songs. He then produced more classics with the Texas Tornados.

“He was literally the person for everyone and that’s why his music was so impactful,” Medrano says.

During this time, Fender was one of the very few Mexican-American musicians to reach mainstream success, so Medrano posed an important question: why isn’t Freddy Fender in the Country Music Hall of Fame?

“You start to notice how much of our history isn’t being told in a national sense,” Medrano says.

She recently started a petition to get him inducted, but she’s not stopping there. She’s working on her master’s degree in information sciences with a focus on conservation and archiving.

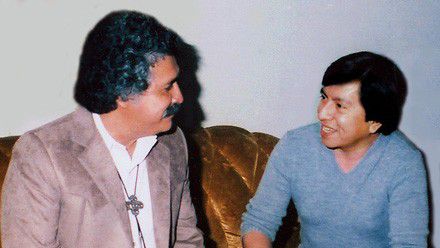

She’s essentially wanting to continue the work that 81-year-old historian Ramón Hernández has done for 40-plus years. Hernández currently runs Street Talk Magazine, where he continues to highlight culture, both past and present. He met up with Medrano and Spectrum News 1 at the Wittliff collections to be interviewed.

“He (Hernández) was the one that taught me about preservation and this is just from his own personal experience. I didn’t learn it from my masters school before. This is literally from someone who does it,” Medrano said.

Hernández responded to her.

“Well, my education only goes as high as high school,” Hernández says.

Hernández has an exhibit named after him in the Wittliff collections, where his photos, memorabilia, and costumes are being preserved.

This passion for preserving his gentes cultura started in the 80s when he was a freelance writer for the San Antonio Express-News and the first artist he ever interviewed — Freddie Fender.

“The reason why I chose Freddy Fender was because he was Chicano, and like Johnny Rodriguez, he was in the national spotlight as a country singer,” Hernández says.

Hernández developed such a strong relationship with the country music star that he was given one of Fender’s suits — the same suit that Medrano was admiring.

“That’s what I want to leave our gente, our raza,” Hernández says.

Hernández glanced at Medrano and praised her for the work she is doing.

“What you are doing for Freddy Fender is highly commendable. I applaud you for it,” Hernández says.

Medrano’s eyes became glossy as Hernández showered her with kind words.

Fender’s music has inspired Dolly Parton, who was inducted into the hall of fame in 1999 and even performed it with him. Country music star Tim McGraw is another who has covered Fender’s music. Medrano believes it’s long overdue to enshrine Fender.

Medrano says enshrining Fender into the Country music hall of fame will allow the next generation of artists that look like her to feel like they belong in spaces like these.

“Freddy Fender is just the start of the door we want to open and have equity in history,” Medrano says.