Anne Van Herynen is an Appleton resident who grew up in Zevenaar, Holland, near the German border. World War II broke out during her formative years, and following is the second of a three-part series of how a young, teenage girl lived through the tragedies and triumphs of one of the most significant periods in our history. Read the first part here.

APPLETON, Wis.— When most of us turn 16, we look forward to securing our driver’s license and exploring the world.

When Anne Van Herwynen turned 16 in 1943, she graduated high school in Holland and, because of the war, went to look for work. She landed a job at Turmac, the large cigarette factory in town.

As for her ride? It was a bike, with wooden wheels.

Now cigarettes were a valuable commodity during WWII and there came a time when several high-ranking Nazis were coming to town and the president of the company, a Jewish man who was prominent in the Underground, went to several of his female employees seeking help. Because of the war, all the restaurants in town were closed, and he asked them if they would prepare and serve them lunch.

“I said to him, ‘It’s a lot to ask but for you, we’ll do it,’’’ said Van Herwynen.

During the lunch, one of the Nazis approached Van Herwynen. “He was looking me over,’’ she said, “and he asked my name, and then says, ‘I have the right son for you.’ And I told him, ‘No, I prefer Dutch quality.’ I looked at my boss and he nearly split.

“Later he said, ‘Anne, Anne, Anne; that was dangerous.’ I said, ‘I know it was dangerous, but I didn’t want anything to do with him.'’’

There were many young men working at the cigarette factory, but once they turned 21 they were required to go to work for Germany, so many went into the Underground. Van Herwynen was determined to help, so she began to smuggle cigarettes out of the factory and bring them to Amsterdam, where they were hiding. Even though food and other necessities had become scarce, “if you had cigarettes,’’ she said, “You could get anything.

“The only way to keep them alive was to get cigarettes to Amsterdam.”“The only way to keep them alive was to get cigarettes to Amsterdam.”

So she would fill the bottom of her bag with cigarettes, nonchalantly walk past the German soldiers at the train station, board the train, and go.

“Only one time a German told me to open my bag,’’ she said. “I had all of my Kotex and underwear on top of the cigarettes. He opened the bag and said, ‘Well, all right.’’’

But it wasn’t long after when the Germans discovered the president of the cigarette company was not only involved in the Underground but was a Jew.

“The Germans killed him,’’ she said. “They shot him.’’

The Germans soon depleted the factory of all of its cigarettes and shut it down. Out of a job, Van Herwynen went to help the lady who ran the bakery in town. She was working there with a young Jewish man when one day the Germans came, blocked off the streets and went door-to-door looking for age-eligible men to come work for them.

Van Herwynen and the baker’s wife quickly put the man in the oven and filled the front of it with wood, to make it look as if it was merely preparation for the next day’s work.

“That was scary,’’ she said. “That was scary. But luckily they didn’t find him. They would have shot him or taken him to a concentration camp, no two ways about it. And we would have got the same treatment. But that’s when you’re young; you don’t think about all that.”

There was another day when Van Herwynen was taking care of the baker’s children. She was alone with them when the bombing started. The English were targeting the railroad station down the street, which the Germans were using to bring in supplies. Van Herwynen quickly took the kids into the basement, but realized she left a pot of beans on the stove. So she went up to grab it and began to head back downstairs.

“I just made it into the basement and the front of the house was blown off,’’ she said.“I just made it into the basement and the front of the house was blown off,’’ she said. “They mis-bombed (the railroad station). They bombed the intersection. The neighbors across from the bakery, the family was gone. Only the husband was left.”

You ask her about her fears, and how she managed to live from day to day.

“You know what happens to you? You kind of get used to it,’’ she said. “It was hard, but what are you going to do?”

And then she continues …

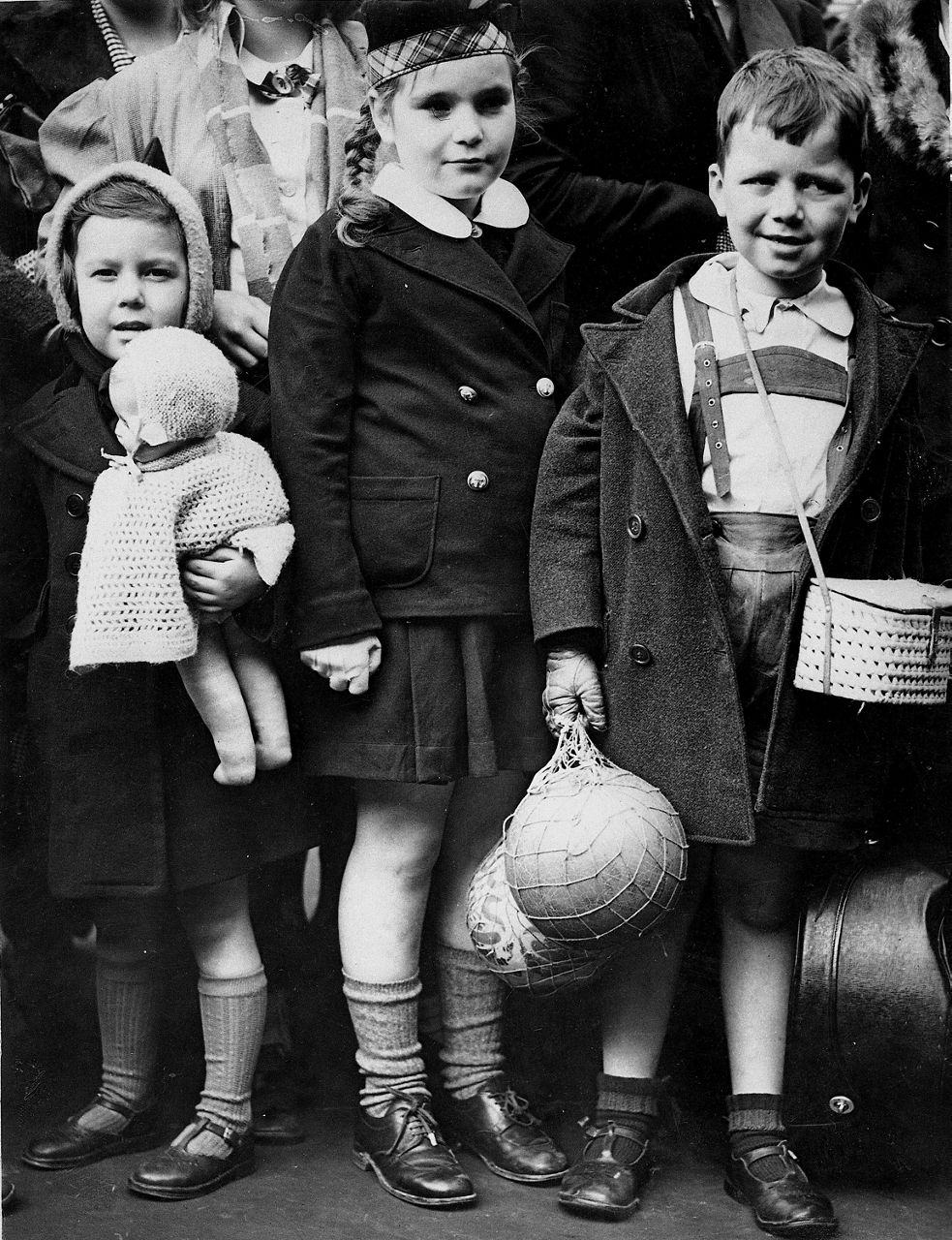

“The kids couldn’t even be outside because, you know, the Americans are over there, they’re over here, the Germans, and they’re trying to shoot at the Americans,’’ she said. “We were caught in the middle.

“I saw a little girl, our little neighbor girl — you know how kids are.’’

And now, Van Herwynen begins to pound on the table in front of her.

“We told the kids, ‘You cannot be outside. Stay in the house,'" she said. “She was little, little. She was outside again and I was just about to run over there to get her, grab her and take her to my house, and she got hit. She got hit by a shell that split her face down the middle. She was dead. That was awful. So my neighbor lady came out and she said, ‘Anne, what are we going to do?’ I said, ‘We have to cover this little girl up before the worms come out of the house.’ You know? Cover her up and tip her back so she could show decently. So we did that. Isn’t that awful? Just a little girl.’’

Van Herwynen then pauses, and there is silence for several seconds before she lifts her head and looks her company in the eye.

“That,’’ she said, “was a tough five years.’’

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at: michael.t.woods1@charter.com

Read part one, here.

Read part three, here.