FORT WORTH, Texas —The city of Fort Worth, like many cities in the south, has a history of hate.

Just two miles from city hall stands a four-story building at 1012 N. Main St. that serves as a reminder the city was once home to one of the strongest Klu Klux Klan communities in the country. The building used to be an auditorium and headquarters for the Fort Worth Klan, also known as Klavern (lodge) no. 101. The structure is believed to be the last standing building purposely built for the KKK in the country.

In 1922, Klavern 101 boasted they were 6,000 strong, city records show Fort Worth’s population in 1920 was 106,482.

When new members were initiated into the KKK they would take an oath of allegiance to the “Invisible Empire,” a name the clan went by, however across Texas they were very much seen. In 1923 when Fort Worth’s finance commissioner W. B. Townsend died, an article in Dallas Morning News said his funeral included the “first Ku Klux Klan funeral parade ever held.”

“In a sense two Ku Klux Klans existed in Fort Worth during the organization’s heyday in the 1920s—two Klans that were as different as, well, day and night.” said Fort Worth journalist Mike Nichols in his article Good Deeds by Day, Dark Deeds by Night: The Ku Klux Klan in Fort Worth. “The daytime Klan gave money to charities and churches and helped needy widows. The nighttime Klan intimidated, tarred and feathered, and lynched those people whom it deemed deserving of its vigilante justice.” In his article published on hometownbyhandlebar.com Nichols gives a detailed history of the Klan in Fort Worth through newspaper clippings.

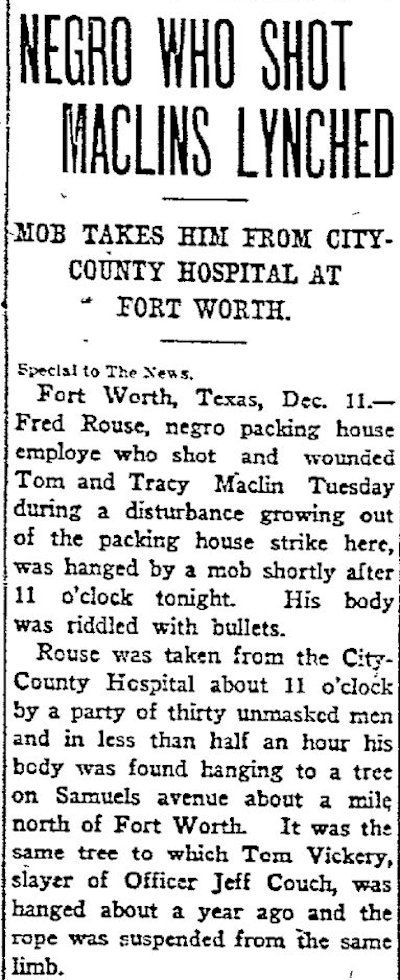

One person who felt victim of Klan 101’s violence was Fred Rouse. The 53-year-old was just getting off work at Swift & Co., a butcher and meat-packing company based in the Fort Worth Stockyards. The year was 1921, and the national packing house workers union had been on strike since December. Black Americans and immigrants, desperate for work, were hired as strike-busters and reviled by the union members.

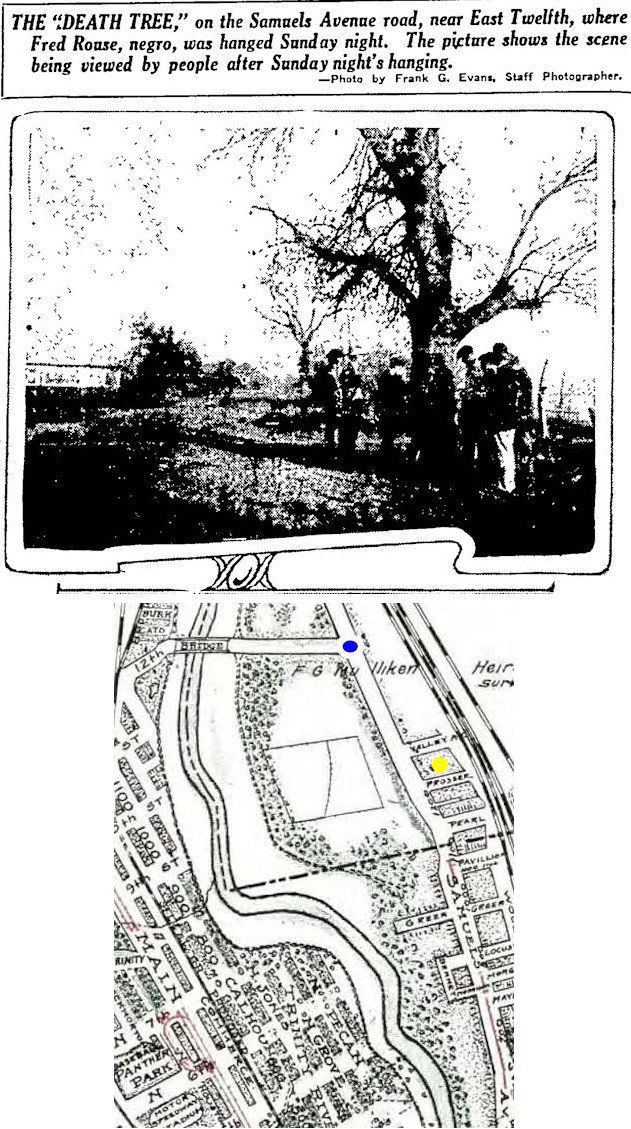

Rouse was threatened by white butchers and subsequently pulled his pistol in self-defense. An angry mob chased the man down East Exchange Avenue, where he was beaten, stomped, stabbed, and then later abducted from his county hospital bed — after which he was shot and hanged from a hackberry tree on Samuels Avenue north of downtown. At the time it was rumored area police officers were responsible for organizing the lynching.

A year prior another Fort Worth man Tom Vickery, a white man, was hung from the same tree known by Klan members as the “death tree,” proving race was just one reason the Klan would attack. Vickery, like Rouse, was abducted. He was being held in a jail cell after allegedly shooting and killing a police officer. Two grand juries failed to indict anyone for Vickery’s lynching, and no one was ever convicted for Rouse’s either.

These grisly murders are just a few in a long line of Texas lynchings, many of which are believed to have had no news coverage. Though the Jim Crow era has since passed, long-simmering racial tension in Fort Worth has bubbled over recently in the wake of a spate of violent encounters between police and Black residents, including the highly publicized murder of Atatiana Jefferson in October 2019.

Healing the people who have suffered at the hands of systematic racism is at the heart of Transform 1012’s mission. The group is a coalition of seven local organizations that have come together to convert the Fort Worth building into the Fred Rouse Center and Museum for Arts and Community Healing.

The building sold after a few years, but it has stood as a monument to Fort Worth’s uncomfortable racist past for almost a century. The building’s current owners, Sugarplum Holdings, L.P., applied for a certificate that would allow them to demolish the historic structure in June 2019.

The Historic and Cultural Landmark Commission of Fort Worth stepped in, and power-couple Daniel Banks and Adam McKinney began the movement to transform the long-abandoned building. The pair are co-directors of DNAWORKS, a service organization that promotes cultural expression through the performing arts, and they have spearheaded the effort to create the Rouse Center.

Other groups involved in the project include Opal Lee's Juneteenth Museum, Sol Ballet Folklorico, the Tarrant County Coalition for Peace and Justice, The Welman Project, Window to Your World, and LGBTQ Saves.

“We’re all from different cultures, different races, different religions,” said Freddy Cantú, co-founder of Sol Ballet Folklorico, an award-winning multi-cultural dance group in Fort Worth. “It’s about coming together and sharing an idea giving back to the community.” A proud gay Latino he feels especially close to the project representing Mexican-Americans and LGBT people who were also victims of the Klan.

“I feel honored to be a part of this coalition comprised of leaders in communities who were once targets of hate crimes by the KKK.” said Cantú.

He hopes to one day see his dancers perform and celebrate their Mexican culture in the very building created with racist ideals.

“It will be a type of cleansing of the space,” he said.

Civil rights activist and recent recipient of the prestigious Hospitality Award from Visit Fort Worth Opal Lee is also a member of the coalition.

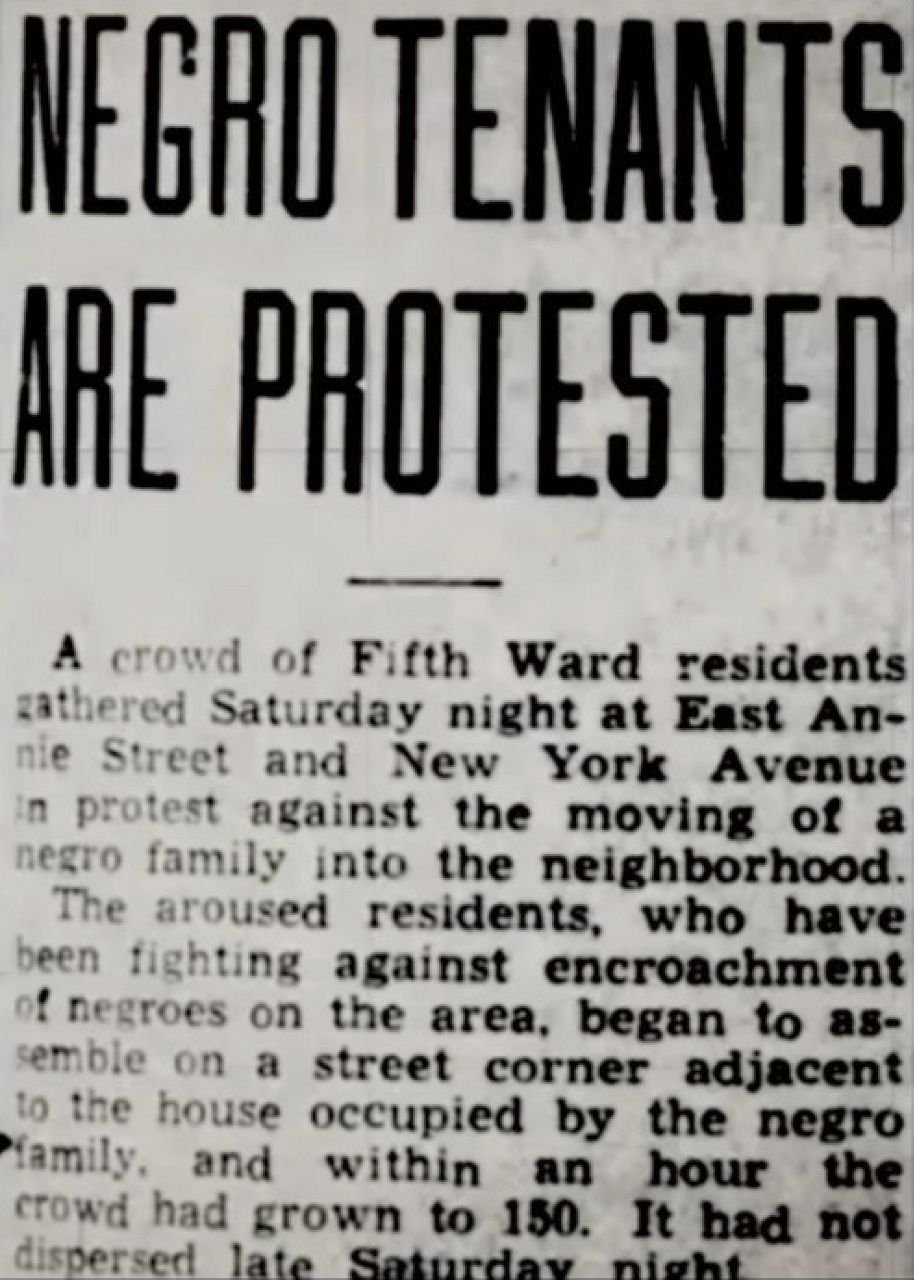

The 94-year-old says she knows first-hand the pain caused by the KKK in Fort Worth. On June 19, 1939 an angry mob of Klan members forced her family out of a mostly white neighborhood by burning their home to the ground. Lee was just 12-years-old but remembers the night vividly.

“When my father came from work with a shotgun the police told him that if he busted a cap, they would let that mob have us,” said Lee. “The mob was five-hundred strong, and the police could not control them. They simply didn’t want any black people in their neighborhood, just off the wall prejudice.”

Also known as the “Grandmother of Juneteenth” Lee recently realized a longtime dream in 2020 by collecting 1.5 million signatures on a petition to create a national holiday for Juneteenth, the day the Civil War-era Emancipation Proclamation was announced in Texas. She hopes the building will one day be home to a private collection she’s curated commemorating Juneteenth’s history.

INSERT PICTURE 9: Pictured is 94-year-old Civil Rights Activist Opal Lee. Credit, DON Photography.

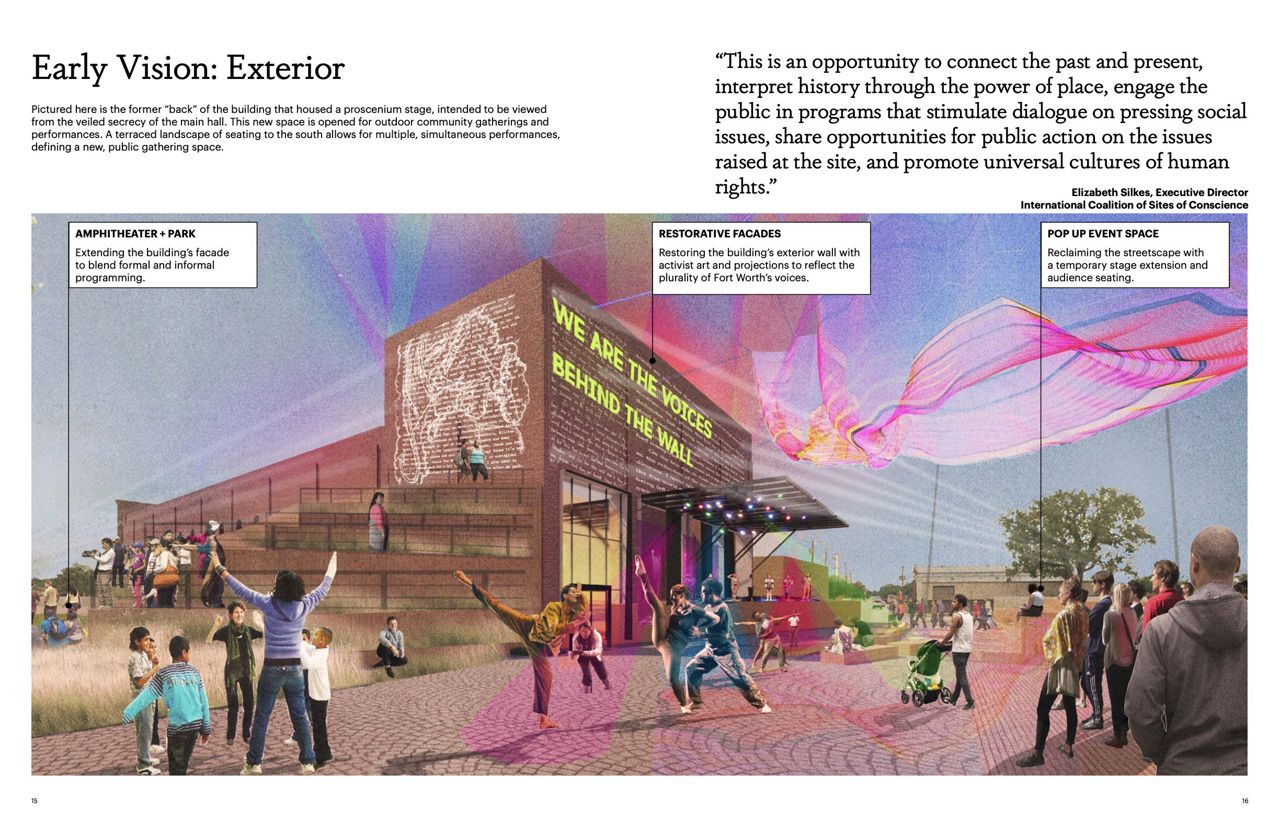

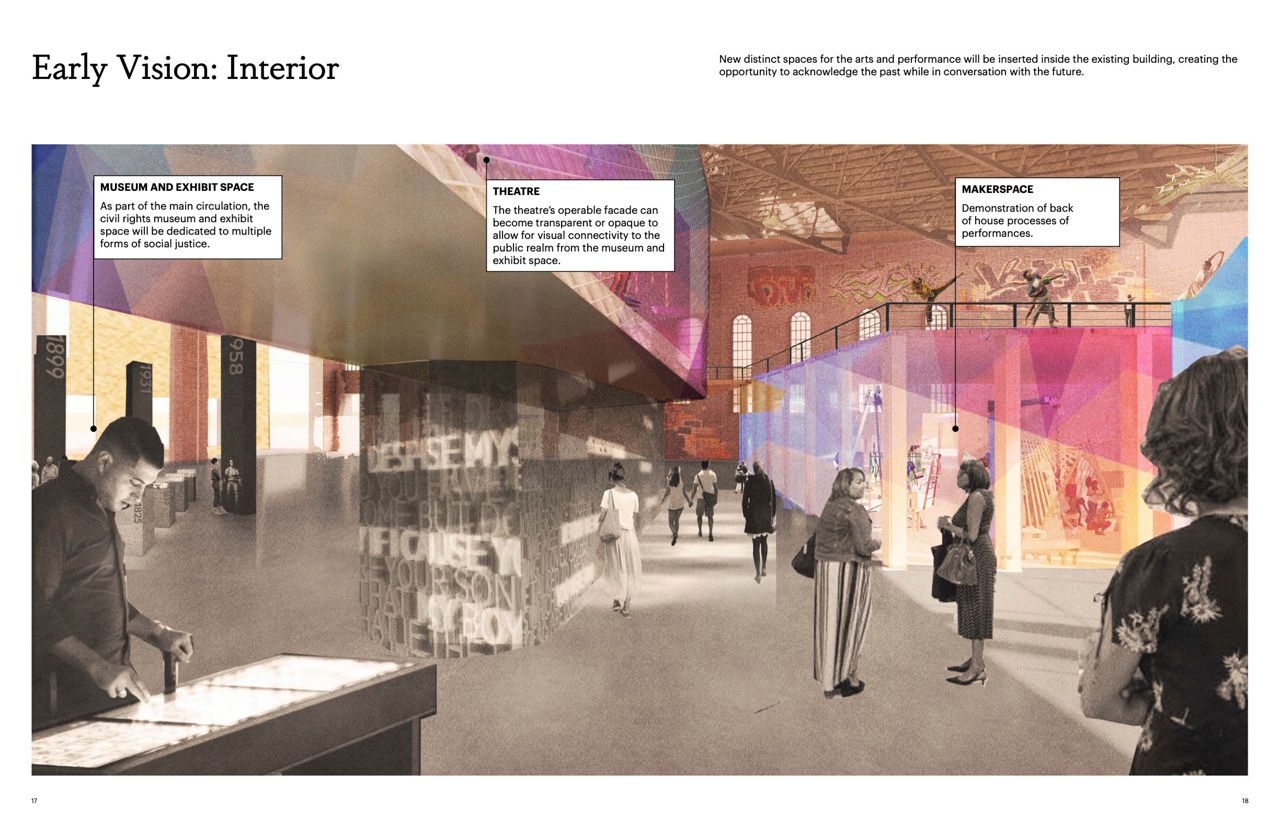

In 2020 the project was awarded a grant by Boston-based MASS Design Group, which has worked on nationally prominent projects such as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. The group created a brochure for the coalition, which depicts some ideas the group has for the space. “We see so much potential here,” said McKinney.

When McKinney looks at the cracked bricks and broken glass, he dreams of an amphitheater, a park with a spot for pop-up events, a museum, a theater, a makerspace, and so much more.

“Now that we have this brochure, we are starting to circulate it to potential funders and donors,” said Banks. “We're still in phase 1, which is about generating community support, generating a business model, and generating some paperwork.”

The group has made several advances in its two-year odyssey to transform the property, including getting estimates from engineering firms and construction companies and reaching out to the owners about purchasing the building. Though Banks said he couldn’t go into much detail, he did confirm his group has been in contact with a representative of the owners about buying the building, and the conversation was “amicable.”

“We’ve been in direct contact with the owner’s representative, and we are in continued conversations about the potential purchase of the building,” he said.

Though COVID-19 has slowed progress somewhat, Banks said the project has never stalled. Quoting author Adrienne Maree Brown, he said it’s “moving at the speed of trust.”

“That's very much how we've been approaching this project — really making sure there's community buy-in and a lot of community conversation,” he continued. “Everything is being done very transparently. We've had conversations with the city. We've had conversations with donors. We've had conversations with stakeholders. We've had conversations with community members.”

At this stage in the process, the coalition is seeking mission-aligned sponsors interested in partnering with the group to acquire the land and make this a reality.

While many in the community have expressed a desire to see the building destroyed the coalitions youngest member 20-year-old Jacora Johnson believes it will serve as a living memorial to anti-racism.

“For me at first, locations like this radiated this sort of malice and hate,” she said. “But, as we’ve gone deeper into this work, and as we’ve taken our time to put our labor of love into it. I can’t help but look at this building and see everything that it’s going to become and I am more than excited for it.”

If you have an interesting story or an issue you’d like to see covered, let us know about it. Share your ideas with DFW Reporter Lupe Zapata: Lupe.Zapata@Charter.com.