DALLAS — Dallas City Council has made it easier for residents to request stop signs as traffic control measures in their neighborhoods.

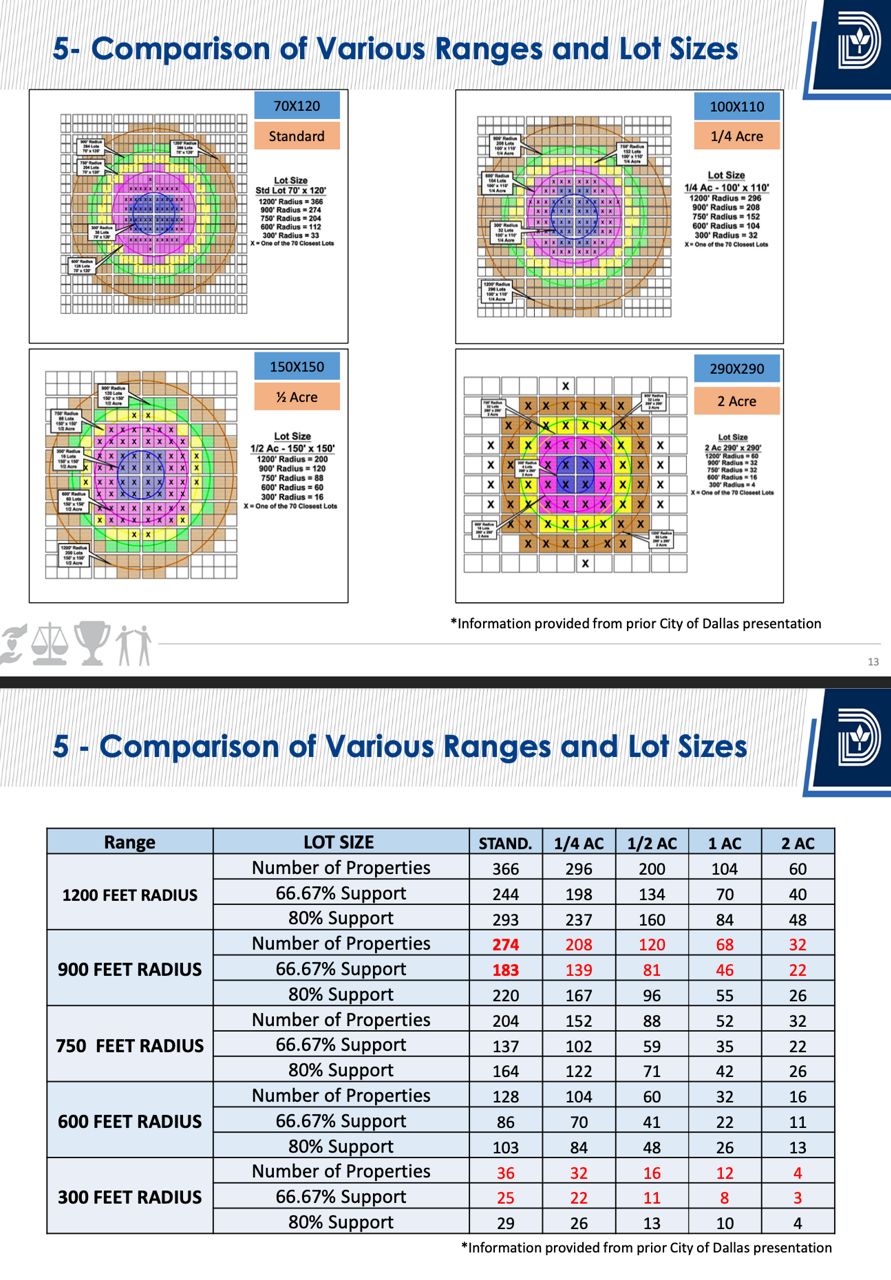

The council approved a policy change reducing the geographic boundaries for neighborhood petitions, meaning residents who want to see a stop sign at a certain intersection only have to collect signatures from two-thirds of the residents living within 600 feet of it. This means that neighborhoods with standard lot sizes would need 86 signatures out of 128 homes. This only applies whenever city staff makes the determination that a stop sign is not warranted.

Under the old ordinance, residents have been able to request a stop sign once staff determines it’s not warranted; however, the geographic boundary requirements for signatures was 900 feet. Mayor Pro Tem Chad West, who initiated this policy change to encourage safer streets for pedestrians and cyclists, advocated to reduce that requirement to 300 feet, but staff and the council committee supported 600 feet instead — still a big reduction of required signatures.

Dallas resident Lori Charles lives in the Winnetka Heights neighborhood in North Oak Cliff. She frequently sees heavy traffic and speeders using her street as a thoroughfare to bypass red lights and other streets with stop signs.

“We have kids running around and I have another kid on the way and I don't want to worry about cars speeding down our street,” Charles said. "We had a cat who was killed by someone speeding the other day, and so whenever those things happen, I always get a lot of calls. One of our neighbors bought a bunch of 'slow down' signs to put up on the street. But unfortunately, I think some people take that as a challenge to go faster. So it's just, I mean, it's hard. It's a great cut-through, I get it but, you know, this is our home and this is our family and these are our kids and we want to keep them safe."

In 2020, Charles decided to take on the task of requesting stop signs from the city. At that time, she faced the daunting task of acquiring signatures from neighbors living 900 feet from the two intersections she was wanting signs at.

"I would say 70 to 100 houses are on our street. And so 900 feet, you had to get two-thirds of the entire street because 900 feet is such a broad amount of signatures. So, at first I thought, 'maybe we can just get one stop sign,' and then I just decided go for it and I go for two and got two-thirds of our entire street. I would go every afternoon and knock on doors and not a lot of people want to answer the door whenever you're sitting with a clipboard. So I would take my 2-year-old and we would try and get five signatures each afternoon.”

Charles got to know many of her neighbors during this signature-collecting process, hearing stories of side-swiped cars, collisions, and overall disdain for the street’s lack of stop signs. She’s got all the signatures in and is awaiting the day the city installs the two stop signs down Winnetka Avenue.

“One woman said, 'I couldn't even teach my kid how to ride a bike on our street' because there were so many cars and so many speeders,” Charles said. "I feel like sometimes the city makes it a little bit harder than it should to get a stop sign. But the whole the neighborhood is really in favor of it and we're really hoping it happens soon. Little bit frustrated it’s taken well over a year. But hopefully, now that we've done our due diligence, the city will make this happen and we'll see it sooner than later and we'll see less activity hopefully. I'm sure people will still run stop signs, but hopefully that’ll at least be a deterrent and we will get slower drivers.”

Charles says she’s now known as the “stop sign lady” to the people in her neighborhood who see her around. She encourages people who wish to see change in the form of a stop sign to follow in her footsteps. While it was a doozy for her to get as many signatures as she did, she doesn’t regret it.

“There's just a lot of red tape when it comes to those things and I get it. I understand that they don't want to just put stop signs up and have people then protest and get angry. But this is a very supported effort in the neighborhood,” Charles said. "I was ready to die on whatever hill I needed to tie on to get these stop signs."

Neighbor Lee Ruiz lives one street over from Charles and frequently sees speeders misusing the roads near them. He says now that the new policy reducing the signature requirement was voted in, he’s sure at the next neighborhood association meeting, traffic-calming measures like stop signs will likely be a hot topic.

“[Getting signatures] has been so hard that no one was willing to do the signatures with a 900-foot radius. Lori did it, to her credit. It was an amazing amount of work and a terrific accomplishment for her. When we next meet with our neighbors and talk through the new process, which is a little bit easier with only 86 signatures required, I expect that more neighbors are going to petition the city for the all way stops.”

Ruiz says a generation ago, Dallas used neighborhood streets to move cars as quickly as possible. He’s a past president of the Winnetka Heights Neighborhood Association, and is one of the people focused on making the streets safer. One of the streets causing the most safety issues is Jefferson Boulevard, along with the Jefferson Twelfth Connector. The connector was installed back in the late 1960s, and it’s a road neighbors want removed.

"Jefferson Boulevard, that is one of the main arteries in Oak Cliff. And it's a perfect example of how a generation ago, Dallas treated neighborhood streets as ways to move traffic as quickly through and out of these historic neighborhoods as possible without regard to safety and without regard to quality of life issues for the people that actually live here,” Ruiz said. "It's three lanes in each direction through the neighborhood. And what's odd about that is when you get to the commercial district, it's only one lane in each direction. And so this was built specifically to create high-speed traffic through our neighborhoods and send cars through as quickly as possible and and it's unnecessary.”

Ruiz said says thankfully, Dallas has the Jefferson/Twelfth Connector Lane Diet/Removal project on the books for completion in May 2024. The project will include future park space, making Winnetka Heights feel like a neighborhood again. Ruiz is also grateful Dallas is working toward its Vision 2030 plan to eliminate traffic fatalities and cut severe injury crashes in half by 2030. He says unfortunately, his neighborhood of Winnetka Heights experienced its own traffic fatality over the summer when a man on a lawnmower was struck and killed by someone speeding down Jefferson Boulevard.

"We have been working to eliminate that lane for many years and we have some momentum now, sadly, resulting from a very tragic death that happened last fall one block from here, where a car from that stoplight found the extra lane on the right, and got to almost 70 miles an hour in this neighborhood street by the time it got to here. And that caused a collision that tragically ended the life of someone that that many of us knew,” Ruiz said. "It's about quality of life and from the city's perspective, it's also economic. I mean, this neighborhood, for instance, is an economic powerhouse for the city of Dallas as as neighbors move in, fix up houses and get them on the tax rolls. And you know, that's not really why it should be done. It's really about quality of life and safety but it all works together."

As Charles and Ruiz await the stop sign installations down Winnetka Avenue, they encourage residents wanting to see traffic calming measures in their neighborhood to not be afraid to advocate for their own safety.

“Because at the end of the day, your home should be safe, your street should be safe,” Charles said. “Don't let the the big obstacle of trying to get signatures deter you from the end goal because it will be worth it.”