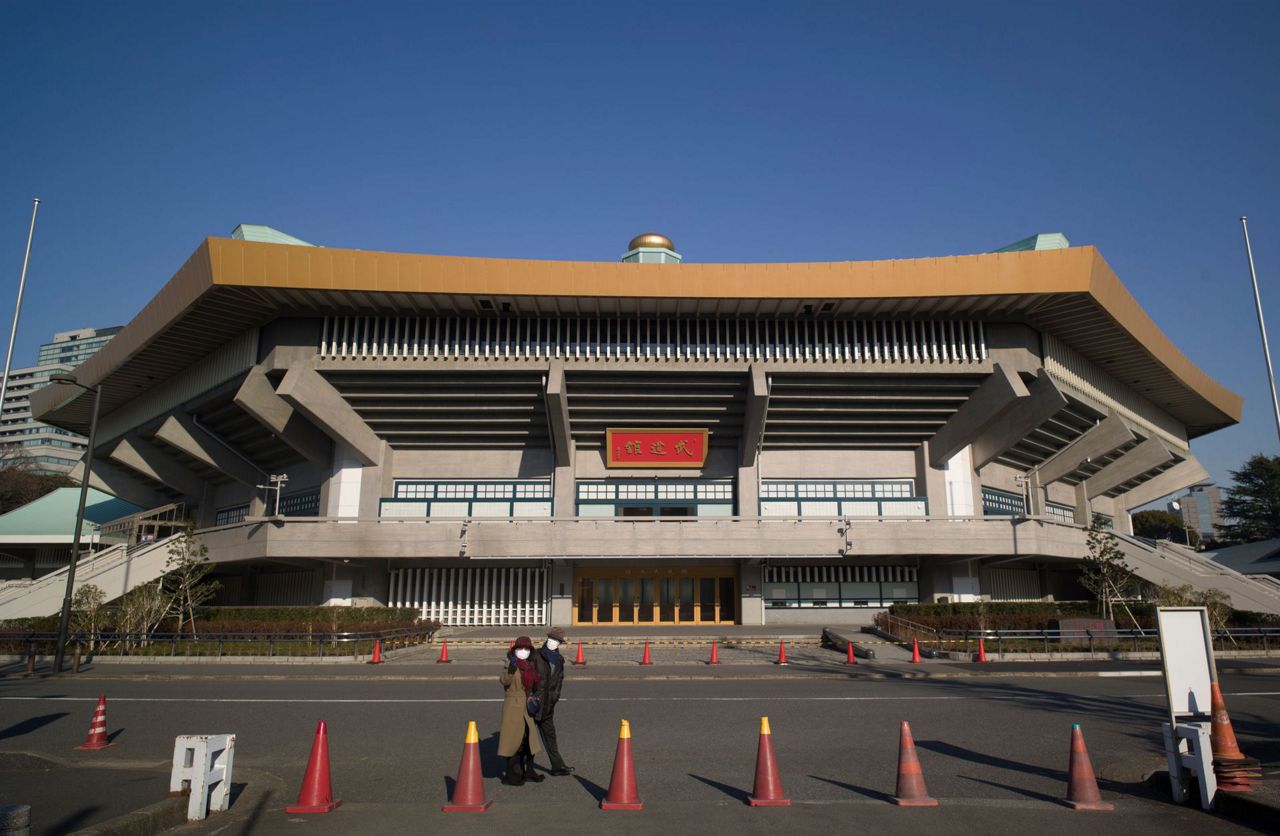

TOKYO (AP) — The Nippon Budokan sits serenely nestled in a verdant park at the heart of Tokyo. Visitors admire the elegant lines of its Buddhist temple-based design before they step into the graceful reverence of the arena, where countless martial arts champions have been crowned since it opened in 1964 with the first Olympic judo tournament.

The Budokan simply feels like a special place, even to those who don’t understand the astounding amount of sports and music history that has occurred under the flowing roof meant to evoke Mount Fuji.

Although no fans will be in attendance when the Budokan hosts judo and the Olympic debut of karate in the second Tokyo Games, this is so much more than a martial arts hall — the literal translation of its name.

“This is where it all began,” said Neil Adams, a two-time Olympic judo silver medalist for Britain who competed at the Budokan in 1978. “The Budokan encompasses all of the qualities that our sport is about in Japan and beyond.”

Widely hailed as the spiritual home of modern martial arts, the Budokan has become a shrine to the greatest achievements of the Japanese sporting spirit — particularly in judo, the homegrown discipline that resonates deeply in Japan. It has even hosted important sporting events of more dubious purity, such as Muhammad Ali’s bizarre fight against Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki in June 1976 under special rules now considered a forerunner to mixed martial arts.

The Budokan also has thrived as a live music venue, hosting nearly all of the greatest talents of the past half-century.

The Beatles were the first rock band to play it in 1966 over five landmark shows. Icons ranging from Bob Dylan and ABBA to Frank Sinatra and Led Zeppelin subsequently held landmark concerts inside. Dylan, Cheap Trick, Ozzy Osbourne and Blur are among many artists to record well-regarded live albums there because of its combination of excellent acoustics and enthusiastic, well-behaved Japanese fans.

This weekend, the Budokan also just might be where the beleaguered Japanese public starts to feel better about the agonizing process of hosting these Olympic Games, which have been battered by scandals and rendered unrecognizable by the coronavirus pandemic because of their inaccessibility to fans.

But nearly 57 years after the Budokan hosted judo's Olympic debut, the mostly empty arena hosts Japan's homegrown sport again in some of the first competitions of the games. The stage is even set in a way that particularly pleases judo traditionalists like Adams: The Budokan’s tatami are on a raised platform with a surrounding safety area, just as in 1964.

Naohisa Takato (men's 60 kg) and Funa Tonaki (women's 48 kg) will attempt to lift their nation's spirits Saturday by claiming Japan's first gold medals of these games. Japanese media are highly focused on the opening-day judokas, suggesting two golds could alter the public's highly ambivalent perception of these games.

Takato and Tonaki also hope to set off an avalanche of success for the powerhouse Japanese judo team, which could contend for every gold medal. The pressure is undeniably enormous, but Takato is prepared for what he'll face in the Budokan after claiming a disappointing bronze in Rio de Janeiro.

“Last time, I was too much focused on the leadoff role to give a boost to the team, which made me nervous,” Takato said. "So this time I won’t think too much about it. I’ll think about my victory and just hope to cheer the team up as a result of it. I believe Tonaki must grab the first gold medal for Japan, and I’ll follow her to be the first male medalist.”

Less than a week after the eight-day judo tournament concludes with the first Olympic mixed team competition, the Budokan will host the Olympic debut of karate, another beloved Japanese martial art finally getting its opportunity to shine on greatest stage.

The fighters who grace the Budokan floor will remember it forever — just ask Adams.

He ranks his victories over his Japanese opponents 43 years ago among the greatest achievements of his sporting life. The Japanese crowds were always respectful, but ardently partisan — and when Adams won, the haunting silence that fell over the Budokan was unforgettable to him.

Like everyone who loves judo, Adams is crushed by the absence of fans over the next week. The Budokan’s importance is inextricably tied to its Japanese crowds, whose combination of enthusiasm and respectfulness have helped to set apart this unique institution.

“The atmosphere is what makes the Budokan such a different place to be, so I feel for all of these athletes,” Adams said. “The Olympic title is the most important thing. That’s what they’ll remember in the end. But it is a shame.”

___

Associated Press writer Kantaro Komiya in Tokyo contributed to this report.

___

More AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2020-tokyo-olympics and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.