"How much snow am I going to get?"

If you see grey hairs on the heads of your favorite TV meteorologists, chances are that simple question created at least some of them.

Considering some of the intense complexities of severe weather and tropical forecasting, you might be surprised to know that most meteorologists point to snow as nature's biggest mystery.

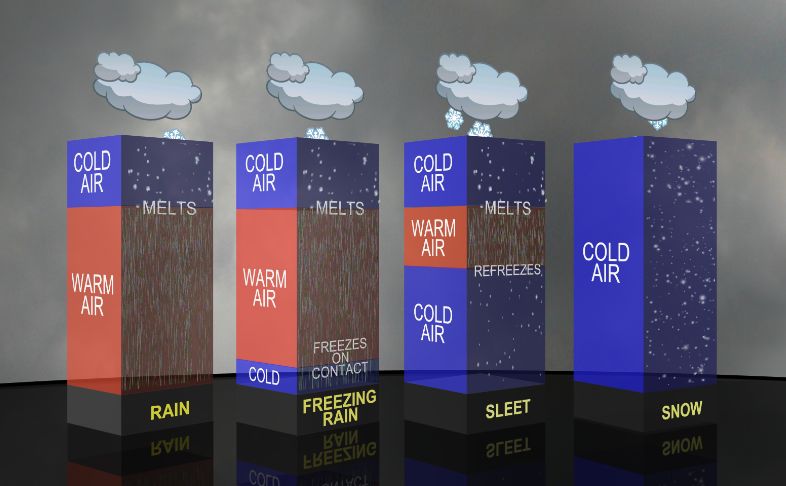

In order to accurately predict snowfall amounts, you need to correctly determine the temperature at the surface, along with temperatures several thousand feet above your head.

Oh, and you need to nail the precipitation forecast down to the nearest hundredth of an inch.

And don't forget to correctly predict the exact direction of the wind, especially for lake-effect snow.

"I would say that for most meteorologists, forecasting snowfall amounts is the hardest thing we do," said Spectrum News Chief Meteorologist JD Rudd, based in Wisconsin. "Forecasting snow amounts is very, very tough. The slightest change in a storm's track or intensity can be the difference between three and nine inches of snow."

Let's start with the basics of snow forecasting. If you're looking to figure out how much it might snow in your neighborhood, you probably need to figure out if it's going to snow in the first place.

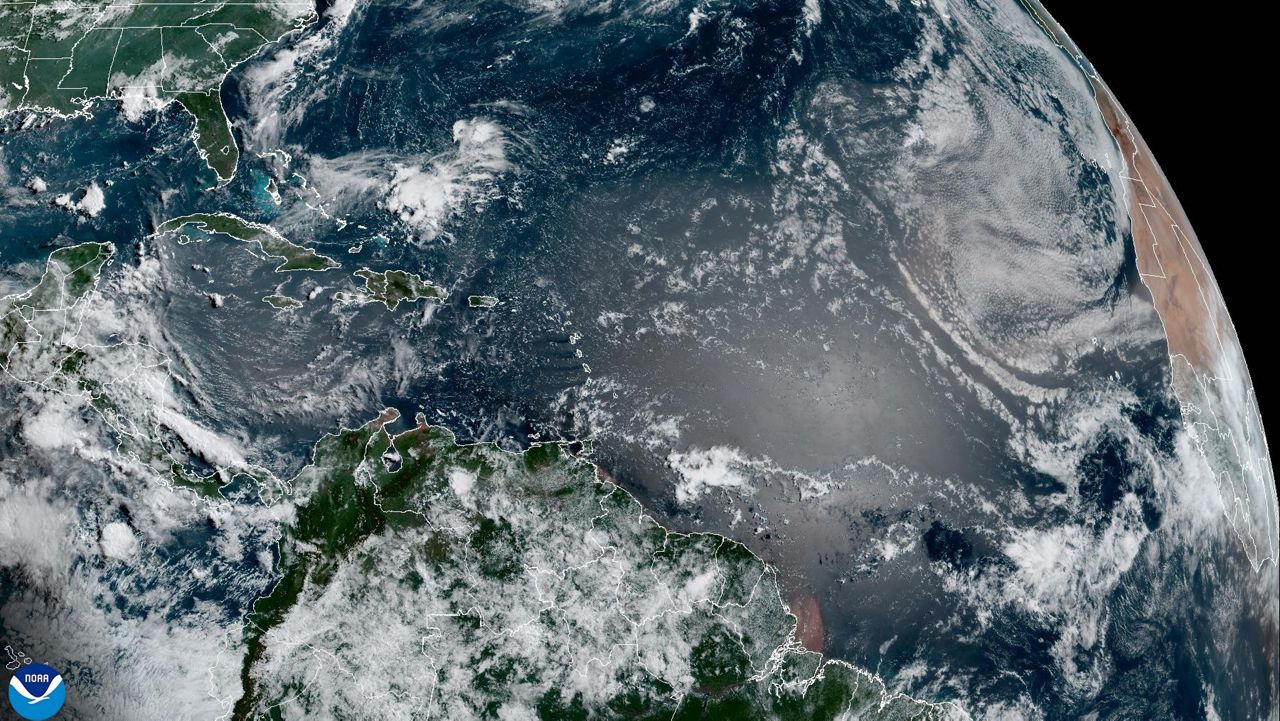

In order to get snow, you need two obvious starting points: cold temperatures and moisture.

Simple enough, right?

However, many times temperatures during a snow event hover right around the freezing mark of 32 degrees. If the temperature is 33 degrees, it can still snow (temperatures just above the surface are often below freezing, allowing snow to still fall), but it may only stick to colder surfaces like car tops or grass.

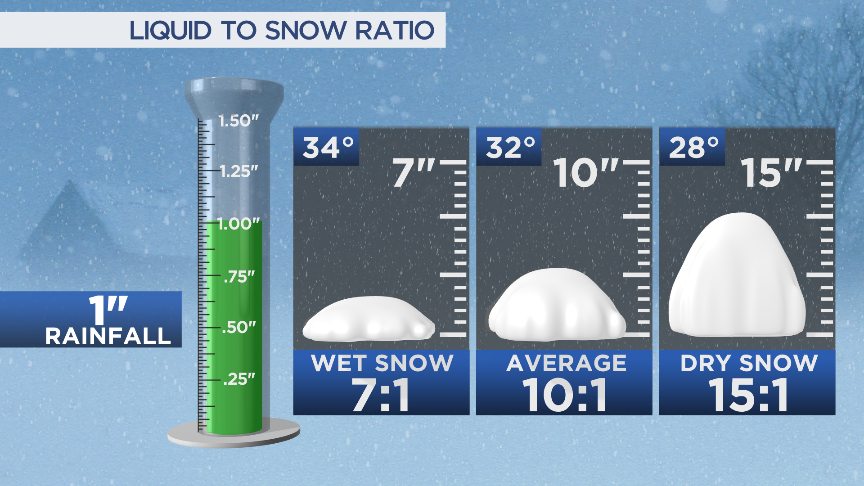

The closer the temperature is to 32 degrees, the higher the moisture content there'll be in the snow that falls. That's because higher temperatures can hold more moisture - and snow in temperatures closer to 32 degrees creates a stickier and wetter snow (perfect for making snowballs).

Usually, when it's 32 degrees and you get snow, it'll accumulate at a rate of about eight-to-ten inches of snow per inch of liquid rainfall. In other words, if you got an inch of rain and converted that into snow, you'd get about eight or nine inches of snowfall out of that inch of rain.

But let's say it's really cold and the temperature is, say, 10 degrees. In that case, the drier, fluffier snow in those colder temperatures accumulates at a completely different rate.

Sometimes, snow can accumulate at 25 or 30 inches per a single inch of rainfall liquid.

So when you're forecasting rain and the temperature is 60 or 65 degrees, it'll have basically no impact on your forecast. But if you're forecasting 25 degrees and you get 20 degrees instead, that could significantly affect how much snow you get.

Tired yet?

"While the surface temperature (matters), what is more important is the temperature throughout different layers of the atmosphere," said Spectrum News Chief Meteorologist Eric Elwell, based in Ohio. "For that, you need good data and good forecast models that understand the situation. You also must know the biases of each model."

All of that is not even factoring in other aspects of how snow might accumulate, like the sun angle, lake-effect snow bands, the sharp cutoff of a nor'easter's rain-snow line, and the middle and upper-level wind direction and temperatures.

Oh, and lake-effect snow depends on the exact angle and timing of the wind, in addition to everything else.

"The hardest part of forecasting (lake-effect snow) is not so much that snow is coming or going. It is which direction the wind will come from and how long it will stay that way," said Spectrum News Meteorologist Kaylee Wendt, based in Buffalo. "One shift and your forecast could be a total bust."

Once you think you've got the forecast pinned down, that's when the communication gets extra tricky.

I've seen them, you've seen them, and they probably fill up your Facebook feed.

When there's even the slightest chance of a snow event in a few days - or even in a few weeks - you might see on social media some color-laden maps filled with caps lock and wild snow total proclamations.

"COMPUTER FORECASTS AGREE, FEET OF SNOW WILL BURY NEW YORK NEXT SATURDAY," might be the hyped headline you'll see on Twitter or Facebook from an official-sounding page like "Cleveland's Weather Center" or "New York Weather Page."

These forecasts are usually wrong, but in the age of social media, they create an avalanche of shares, likes, and hype that's difficult for even the most skilled and sober-minded meteorologists to push back on.

"There are the social 'media-rologists' that immediately post models many days out and start internet rumors," Elwell said. "These people typically don't understand the nuances and biases of the models, especially beyond a couple of days."

Here's the thing: Computer forecast models are free and easy for anyone to use. It's also free and easy to create a social media account.

Because snow forecasts are so important and closely watched, a wild forecast promising huge amounts of snow–no matter how inaccurate it might be–can generate plenty of shares and attention.

That combination often leads to a lot of social media-driven misinformation.

While this problem isn't necessarily exclusive to winter weather forecasting, so-called "social media-rologists" seem to have extra love for spreading disinformation around potential upcoming snowstorms. Any meteorologist reading this is probably nodding their head, and for good reason.

If you're reading this, though, you're already accessing the most accurate and hype-free forecast that you can get. And that's extra important when discussing a forecast–and its communication–considering how difficult it is for meteorologists to forecast exact snowfall amounts.

If the public isn't fully grasping or understanding the uncertainty of an upcoming snowfall forecast, it's probably on the communicators who provide the forecasts, as well.

That means we, as meteorologists, clearly have work to do in how we effectively communicate forecast snow totals and winter weather hazards to the public.

"I think when it comes to forecasting snow amounts, you have to be honest with people," Rudd said. "Tell them what you know and what you don't know. If the amounts could really change, say that."

Of course, predicting even what kinds of shifts to the forecast could take place is difficult, simply because there's so much that goes into one.

"A wind direction shift and someone you said would get a foot of snow gets an inch and you HEAR about it from viewers," Wendt said. "No matter how much experience, I feel as though meteorologists in (the Buffalo) area are kept on their toes."

But hopefully now at least you understand part of why forecasting snowfall amounts, and accurately delivering that message to you, is such a challenge.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.