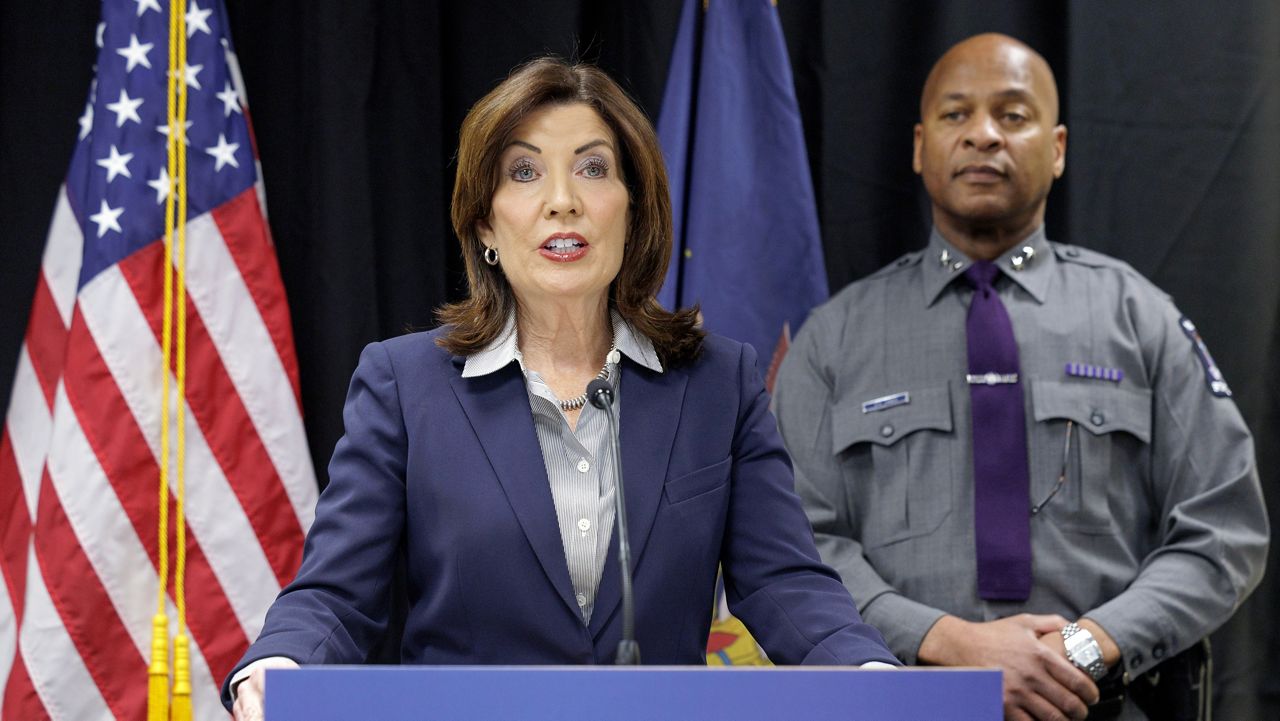

Top state court officials told lawmakers Tuesday that judges in New York don't need required training to better understand the state's bail laws as Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed further changes to the cashless bail system in the upcoming budget.

Hochul wants to change the law to end the "least restrictive" standard requirement, and has said it would end confusion for judges setting bail for serious charges and repeat offenders.

But Acting Chief Administrative Judge Tamiko Amaker says judges aren't confused by the state's bail laws that have changed several times in the last few years and decide to set bail based on the facts of an individual case. She also dismissed lawmakers' push to mandate training for judges on the topic.

"It really just depends on the circumstances of that specific case," Amaker said at the beginning of Tuesday's 10-hour hearing. "Just because you have the ability, just because it is a qualifying offense and you can set bail, doesn't mean that you will."

Republicans continue to call for a full repeal of changes to a cashless system the Legislature first made in 2019.

Representatives with Hochul's office did not respond to requests for comment.

Amaker said judges received more than three hours of training on the law at a summer conference last year.

The Office of Court Administration has offered the training several times at its annual seminars for new judges and the department's reoccurring summer sessions, OCA spokesman Lucian Chalfen said Tuesday.

The state has roughly 1,350 paid judges. Chalfen would not answer questions about how many have not had the training, but said nearly all judges with criminal jurisdiction have participated.

Amaker wouldn't answer lawmakers' repeated questions about what materials are used to educate judges about bail in New York, nor a list of which justices have completed the training.

"If judges attend, they sign in and out of every session," Amaker said. "I don't know that that information is retained. It's usually just so we can figure out who has attended, how many meals we're going to have, to make sure we have housing for those judges. ...We provide pretty clear training."

The Office of Court Administration makes the educational materials available to justices who did not attend the bail law session, she added. Each judge is given a list of bail-qualifying criminal offenses.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Brad Hoylman-Sigal questioned the efficacy of the past judicial training, citing several instances where judges made decisions to set bail or not that were not in keeping with the law.

State court system officials do not measure if the training is effective, Amaker said.

The state's Chief Administrative Judge and Chief Judge on the Court of Appeals have the power to hold training seminars and to set the agenda, Chalfen said.

Amaker also would not answer lawmakers' questions about reports former Chief Judge Janet DiFiore continued to use state-funded drivers and a security detail after she resigned amid an ethics probe last year, and without proper approval.

Deputy Senate Majority Leader Mike Gianaris says the court administration's refusal to be transparent will impact how the Legislature responds to its request for $3 billion in the next state budget.

"This is the moment where the public gets to hold them accountable for the spending of their tax dollars, and if they're not going to tell us how that's happening, I think we have to be extremely skeptical about what we give them and what they need for the courts to function," the Queens Democrat said. "...It was not only disappointing, but disturbing that an entire branch of government is stonewalling and not being very transparent about what they've done.

"This is not the way the court should be operating," he added.

A confidentiality statue in state law prohibits the Commission on Judicial Conduct from confirming if DiFiore was the subject of formal disciplinary charges.

"I can't confirm or deny if we were investigating the chief judge or if she was the subject of formal disciplinary charges," said Robert Tembeckjian, administrator and counsel with the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

New York is one of 12 U.S. states with a similar confidentiality rule protecting the judiciary.

During testimony, Tembeckjian pleaded with lawmakers to change state law that prevents transparency when it comes to judicial discipline and publicly release information about ethics probes.

New York justices who go through a formal disciplinary proceeding — which cannot be publicized under the current law — frequently resign or retire suddenly.

The commission can only proceed with charges if the result of the case is the justice's removal from office. With the judge already gone, it prevents the commission from referring formal charges and seals the details of judicial misconduct from the public for good.

"In the executive and legislative branches, you can't avoid discipline for misconduct by leaving office early, but in the judiciary, you can," Tembeckjian said. "And that seems, to me, to be something that needs to be remedied."

A New York justice under investigation leaves office abruptly about twice per year, Tembeckjian said.