WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court is preparing to hear a gun rights case that could lead to more guns on the streets of New York and Los Angeles and threaten restrictions on guns in subways, airports, bars, churches, schools and other places where people gather.

The case the justices will hear Wednesday comes as gun violence has surged, and it could dramatically increase the number of people eligible to carry firearms as they go about their daily lives. The case centers on New York’s restrictive gun permit law and whether challengers to the law have a right to carry a firearm in public for self-defense.

Gun control groups say if a high court ruling requires states to drop restrictions, the result will be more violence. Gun rights groups, meanwhile, say the risk of a confrontation is precisely why they have a right to be armed for self-defense.

Gun rights advocates hope that the court with a 6-3 conservative majority is poised to side with them. They want the court to say the New York law is too restrictive, as are similar laws in other states. Gun control advocates acknowledge the court’s composition has them concerned about the outcome.

“The stakes really could not be higher,” said Jonathan Lowy, chief counsel at the gun control group Brady.

The court last issued major gun rights decisions in 2008 and 2010. Those decisions established a nationwide right to keep a gun at home for self-defense. The question for the court now is whether there’s a similar Second Amendment right to carry a firearm in public.

The question isn’t an issue in most of the country, where gun owners have little difficulty legally carrying their weapons when they go out. But about half a dozen states, including populous California and several Eastern states, restrict the carrying of guns to those who can demonstrate a particular need for doing so. The justices could decide whether those laws, “may issue” laws, can stand.

The fact that the high court is hearing a gun rights case at all is a change after years in which it routinely turned them away. One gun case the justices did agree to hear ended anticlimactically in 2020 when the justices threw out the case.

But following the death of liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg last year and her replacement by conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the court agreed to wade into the gun debate again.

Eric Tirschwell, the legal director at Everytown for Gun Safety, said there’s “reason to be concerned” for groups like his that “a type of law that the court was not interested in or willing to review in the past, they now are.”

The New York law the court is reviewing has been in place since 1913 and says that to carry a concealed handgun in public for self-defense, a person applying for a license has to demonstrate “proper cause,” an actual need to carry the weapon. When local officials issue a gun license, it’s either unrestricted — allowing the person to carry a gun anywhere not otherwise prohibited by law — or restricted, allowing the person to carry a gun in certain circumstances. That could include carrying a gun for hunting or target shooting, when traveling for work or when in backcountry areas.

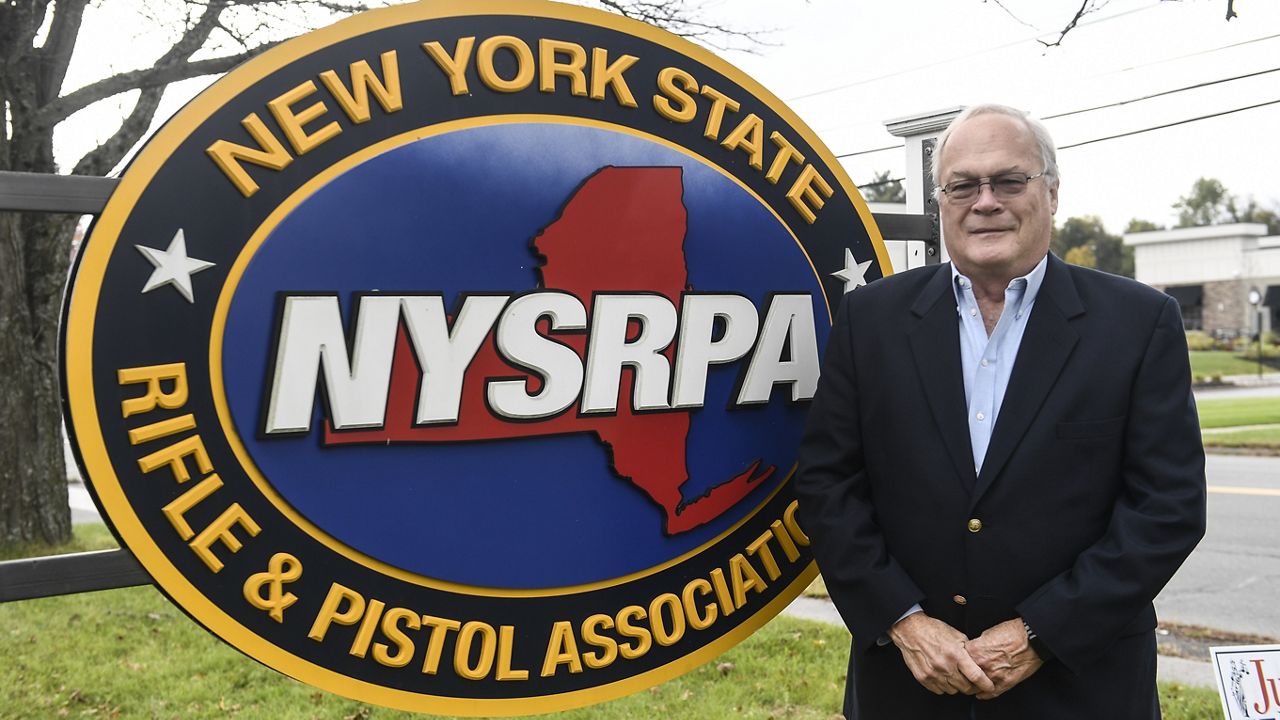

The New York State Rifle & Pistol Association and two private citizens challenging the law have told the Supreme Court that it “makes it effectively impossible for an ordinary, law-abiding citizen to obtain a license to carry a handgun for self-defense.”

Lawyers for the group say the text of the Second Amendment, along with history and tradition, supports their argument that there’s a right to carry a gun outside the home. The group also says that New York’s law has discriminatory origins, that it was originally intended to give officials wide latitude to keep guns out of the hands of newly arrived immigrants from Europe, particularly Italians.

New York, for its part, denies that and says that the Second Amendment allows states to restrict the carrying of guns in public. It, too, points to history, tradition and the text of the Second Amendment. The state says its restrictions promote public safety, pointing to research that says that places that restrict the public carry of guns have lower rates of gun-related homicides and other violent crimes. New York says its law isn’t a flat ban on carrying guns but a more moderate restriction.

Tom King, president of the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, said in an interview that part of the problem with New York’s law is that the chances a person will get an unrestricted permit depend on whether he or she is in a rural or more urban area of the state.

Both gun rights and gun control advocates say that it’s unclear how broadly the court might be willing to rule and that they will be closely watching arguments for clues, particularly from the court’s three newest members.

The three appointees of former President Donald Trump — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett — are conservatives but were not on the court when the justices last issued major gun rights rulings. Their actions so far have given gun rights advocates reasons to be hopeful, however.

In 2011, as an appeals court judge, Kavanaugh argued in a dissent that the District of Columbia’s ban on semi-automatic rifles and its gun registration requirement were unconstitutional. Last year, he urged the court to take up another guns case soon, saying he was concerned that lower courts were not following Supreme Court precedent.

Gorsuch, for his part, would have decided the 2020 gun case his colleagues threw out. And Barrett, as an appeals court judge, wrote in a dissent that a conviction for a nonviolent felony shouldn’t automatically disqualify someone from owning a gun; she said her colleagues were treating the Second Amendment as a “second-class right.”

Gun control groups hope, however, that conservatives might still vote to uphold New York’s law. A group of prominent conservatives, including former federal appeals court judge J. Michael Luttig, has urged the court to do so in a brief to the court. And earlier this year, in a 7-4 decision, judges on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a challenge to Hawaii’s permit regulations. Conservative judge Jay Bybee wrote that a “review of more than 700 years of English and American legal history reveals a strong theme: government has the power to regulate arms in the public square.”

The court’s three liberal justices are widely expected to side with New York.

Depending on what the justices ultimately say, other states’ laws could also be affected. The Biden administration, which is urging the justices to uphold New York’s law, says California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Rhode Island all have similar laws. Connecticut and Delaware also have “may issue” laws, though they are somewhat different.