Ten years ago, Gov. Andrew Cuomo achieved a victory that remains arguably his most wide-reaching success: the legalization of same-sex marriage in New York.

At a news conference celebrating the passage of the measure in the state Senate and signing it into law, Cuomo discussed the Rev. Martin Luther King saying the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice. It bends that way, Cuomo said, but sometimes you have to bend that arc yourself.

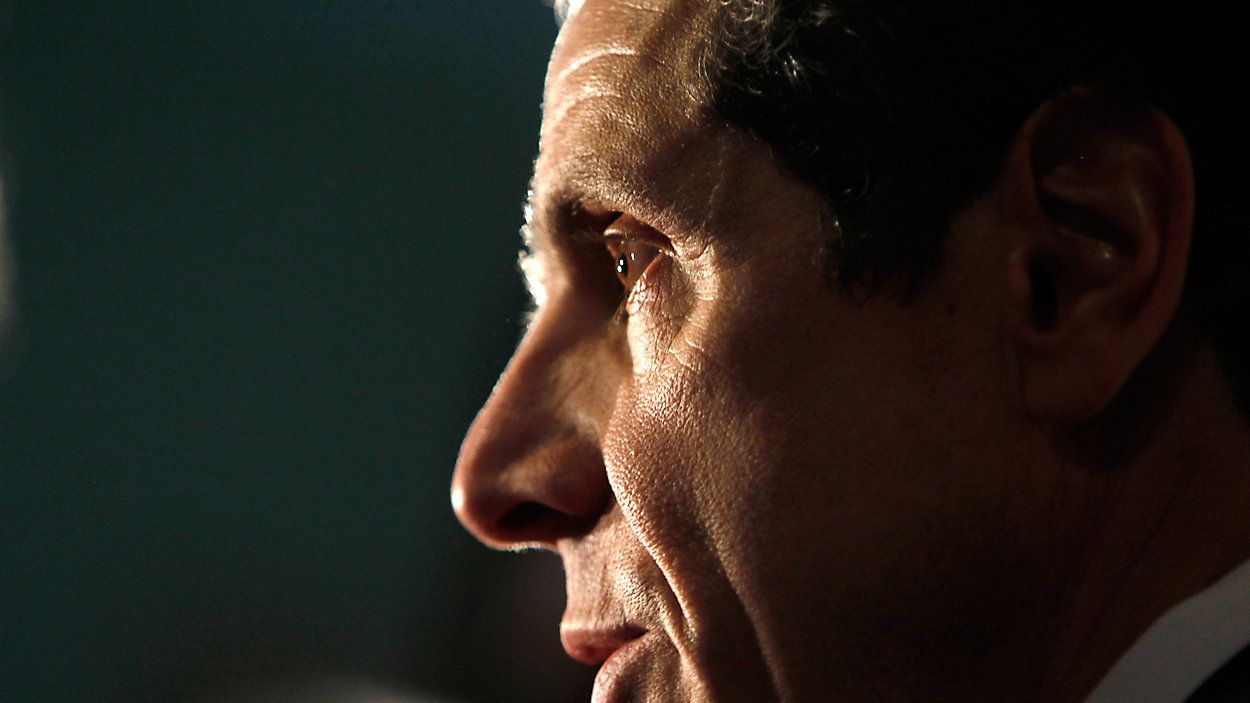

Over the 10 years Cuomo has been in office, Cuomo did plenty of bending and arm twisting as he sought to mold the state and the state's government under his direction. A student of power in an inherently powerful position, Cuomo led a fractious and factional state almost without question, marginalizing and belittling his critics along the way.

Cuomo was never someone who seemed interested in money, even as his gubernatorial salary grew during his time in office. He was more interested in a different kind of accumulation: Power.

Cuomo held power over the vast political bureaucracy of New York, held power over individual people, held power over a Legislature he would insist is not "a debating society" whenever the brakes would be pumped on his desired goals.

Now Cuomo is leaving office amid allegations he sexually harassed multiple women and that his administration hid nursing home fatality data during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The arc has finally bent back on the governor himself, reversing a power dynamic he has benefitted from for his entire adult life.

“Andrew Cuomo will go down as New York’s Richard Nixon," said Robert Bellafiore, a former reporter for the Associated Press who served as a senior aide to Gov. George Pataki. "He got things done that probably nobody else could have but, like Nixon, was brought down by an unprecedented, self-inflicted scandal. He also left a template for future governors for how to use the levers of government for political gain and public theater.”

Supporters of the governor say Cuomo at his best knows what levers to pull to things done. Indeed, Cuomo himself over the years has stacked up his state budgets approved before the April 1 deadline as a totemic metric of success. Critics allege he's a bully, a secretive and cynical wielder of backroom leverage that masked deep dysfunction.

It may be ultimately the governor is a blend of both.

Cuomo learned political and power dynamics first hand from his father, volunteering for Mario Cuomo's failed campaign for mayor of New York City in 1977, the summer of Sam and the year the Bronx burned.

He would serve as a $1-a-year advisor to his father in the governor's office and later forge his own path tackling homelessness and housing issues.

What the younger Cuomo did not learn from his father, a soaring orator, he would learn from President Bill Clinton in the hothouse politics of Washington DC in the 1990s.

During Cuomo's stint as housing secretary in the Clinton cabinet, the president would face a sex scandal of his own. At the time, power dynamics between a president and a young intern were questioned, but it would take another generation before a reckoning would occur over how society views harassment and workplace misconduct.

In 2002, Cuomo would seek to avenge the 1994 electoral loss of his father, launching an ill-fated gubernatorial campaign to take on Pataki, a Republican.

He never got the chance.

The Democratic establishment was backing Comptroller Carl McCall, New York's first Black statewide elected official, to take on the incumbent Republican. Cuomo, never so powerless, groused at a news conference it was his aides who misled him.

Cuomo ran head long into failure. Democrats found him too abrasive. He accused Pataki of holding Rudy Giuliani's coat during the Sept. 11 attacks at a time when it was still seen as taboo to politicize the event.

He dropped out of the race before the primary was held, blaming his staff for bad advice. His marriage disintegrated, with the sordid details playing out in New York City's tabloid press.

By 2006, he was launching a comeback. This Andrew was not the Andrew of 2002. He was chastened, the rough edges smoothed off. He handily won a race for attorney general, an office that had grown in stature under Eliot Spitzer. Cuomo promptly used the perch to tackle issues like student loan debt.

The attorney general years were a foreshadowing of Cuomo as governor: Taking an inherently powerful job and somehow ratcheting that power to the nth degree.

And he would investigate Spitzer, issuing a scathing report of a classically Byzantine Albany scandal that was Troopergate.

When Spitzer self-immolated in a prostitution scandal, Cuomo would also investigate David Paterson. An ally of Cuomo's, Larry Schwartz, would take over the role of secretary to the governor, giving Cuomo what amounted to a prime minister-in-waiting as he prepared to take office in 2010.

Cuomo that year faced Carl Paladino, a sort-of prototype for Donald Trump.

At the time, New York and the rest of the country was in the throes of the Great Recession. The tea party-infused Republican Party was encouraging a revolt against government spending and taxes.

Cuomo, like Bill Clinton of the 1990s, sought to take the issue from the Republicans.

He capped property tax increases. He limited new spending to less than 2% in the budget. He worked with Republicans in the state Senate who recognized a fellow deal maker.

Cuomo's popularity with Republicans in the first term was curious. The Democratic governor did little to encourage a Democratic takeover of the chamber to match the party's domination of the state Assembly.

In turn, Republicans initially did not match the culture war fights that were beginning to engulf the GOP elsewhere. They allowed successful votes to move forward first on same-sex marriage and later on a sweeping gun control measure.

Much of Cuomo's power over the first two terms was realized through a weakened Republican majority in the state Senate which needed the aid of a breakaway faction of Democrats to maintain control.

But, like many power sharing arrangements, it was all temporary.

The election Trump in 2016 solidified how untenable it would be for Cuomo to continue working Republicans, even as he sought to appeal to a new president most members of his party found ghastly.

When Cuomo first ran in 2010, he launched his campaign on the steps of the Tweed Courthouse, named for all-but forgotten figure in history associated with the backroom graft of Tammany. Albany under this governor wouldn't be a joke anymore for New Yorkers.

But nearly every powerful man in state government in the last decade has faced scandal. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver: guilty of bribery. Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos: guilty of fraud. Deputy Senate Majority Leader Tom Libous: Guilty of lying to the FBI. Sen. Jeff Klein: Lost re-election after he was accused of sexual harassment.

A commission to investigate government corruption, launched by Cuomo after lawmakers would not agree to new ethics measures, was shuttered just as lawmakers reached a deal.

Cuomo did not seem to understand the outrage. It was his commission, he argued. I could make, I can un-make it, he said.

And then there was Joe Percoco. Cuomo considered Percoco a virtual brother. He was fixer for Cuomo, a super-advance man who knew how to set up spaces for events as the governor wanted and was his eyes and ears with the Legislature.

Percoco had a reputation, that he seemed to revel in, of being the governor's personal heavy.

He was also quietly receiving bribes connected to a Hudson Valley energy project.

Percoco's corruption case was tied into a broader scandal that swallowed up prominent developers who were also donors to the governor's campaign and part of the wide-ranging Buffalo Billion economic development project.

After Cuomo's win in 2010, his administration focused heavily on reviving western New York, a region Paladino had done well in electorally.

Cuomo was never implicated. Though singed, Cuomo continued to forge ahead with the Buffalo Billion -- creating a template for how all future scandals would be handled. No mistakes would be admitted. Forge ahead.

In the months before the pandemic, Cuomo was living full-time at the mansion. He seemed unlikely to make a run for president and was likely content with surpassing his father's time in office with a fourth term in 2022.

Cuomo election campaigns took a smash mouth approach to electoral politics. The campaigns were also another display of raw Cuomo power: His campaign donations, his ability to command media attention against lesser-known opponents.

He beat back progressive challenges in 2014, first by ignoring his opponent Zephyr Teachout, and then by relentlessly campaigning in 2018 when challenged by Cynthia Nixon.

He would spend tens of millions of dollars, raised from a variety of the state's power players in the health care and real estate industries.

Cuomo would also form minor party ballot lines to boost his vote total, even going as far as to create the "Women's Equality Party" ballot line with himself the leading candidate. Seven years later, the irony is not lost on many in Albany.

Cuomo would war with the Working Families Party, a progressive ballot line that cross endorses Democrats, with every four years a minor melodrama over whether he would secure their backing. After running on their line in 2018 when the party initially endorsed Nixon, Cuomo then moved to make it harder for the WFP to retain their ballot status.

As COVID-19 spread across the state, Cuomo's prominence rose to national heights. The news conference was filled with inside jokes only devotees would have gotten, mixed in with essential updates confused and anxious New Yorkers were looking for, and not getting, from Washington.

Cuomo's hype grew to the point where he released his second book since taking office, a chronicle, mostly, of how he held press conferences.

But the news conferences were the first time the longest tenured governor in America was introduced to most of the country. He was presented as a cuddly guy, a stern dad who told people it was all for their own good.

But there was always a different man behind the oak-paneled walls in Albany.

There, Cuomo was an intense and driven manager, a governor who wielded the phone like a weapon to call and often berate lawmakers, fellow Democrats and journalists.

There was never anything too small for Cuomo to control.

He once had a top aide read a state worker's employee file on air after the worker spoke to a local reporter without clearing it first.

"Guilty, I plead guilty," Cuomo told Charlie Rose once when asked if he is a micromanager.

It is possible Cuomo never actually wanted to be president of the United States, despite the rampant speculation every four years. Being governor of New York was wrapped up in his identity.

In 2011, Cuomo was riding high in the polls. He insisted in a radio interview that it wasn't about him personally, but the pride New Yorkers feel about their state government again.

"I am the government," he said.