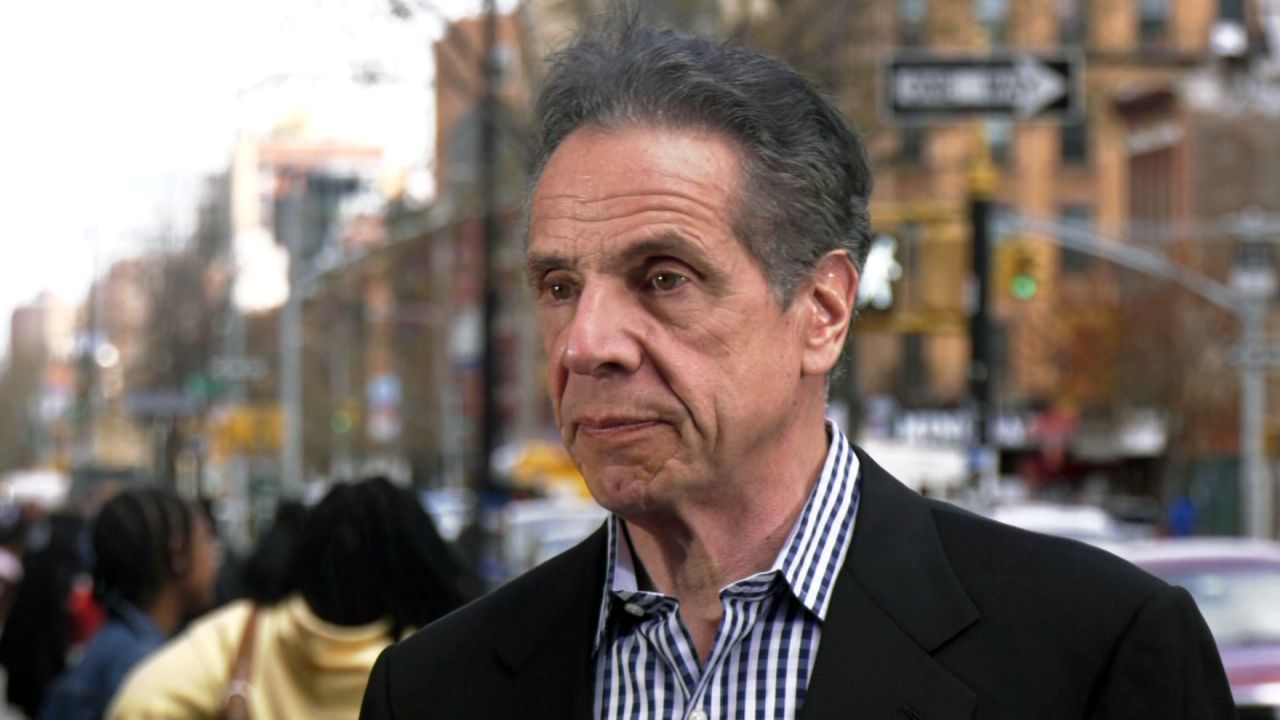

This week, a court ordered Gov. Andrew Cuomo's administration to release reams of additional data for nursing home deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It's being called a victory for open government and transparency surrounding a gut-wrenching aspect of the ongoing crisis. But it's also a victory for a soft-spoken journalist and health policy researcher behind the Freedom of Information Law request initially made in August.

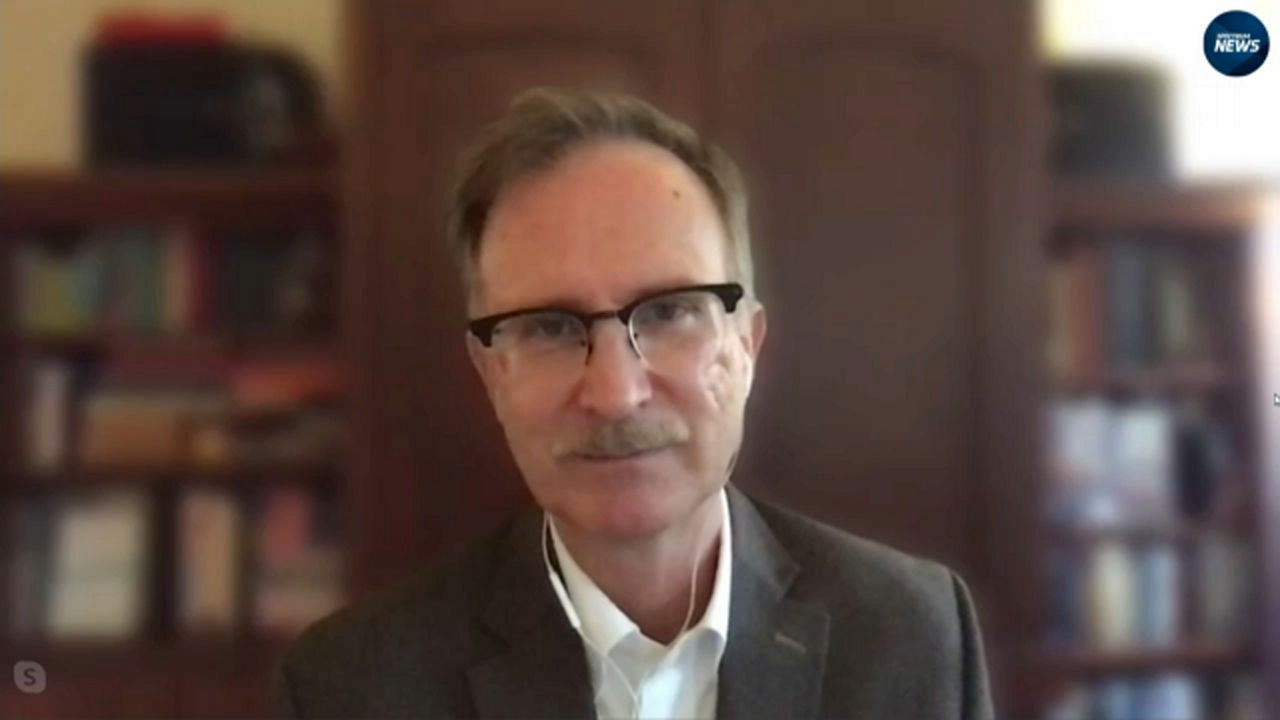

The Empire Center's Bill Hammond was the driving force behind the right-leaning think tank's lawsuit to drag the data into the sunlight.

Hammond, a former columnist in Albany for The New York Daily News, is not a rhetorical bomb thrower, though he does maintain a dry wit on his Twitter account. Instead, he buries people with facts.

"His fair and objective, dogged, journalistic approach to getting the answers is a big part of what makes him so valuable to our work at the Empire Center and to every New Yorker who cares about the future of this great state. That approach is what leads to better outcomes — as it did in the case of extracting taxpayers’ data from the Department of Health," said Tim Hoefer, the Empire Center's president and CEO.

"Success, in this instance, is giving New Yorker’s access to data and analysis that explains what happened, that informs better questions, and that will help prevent future bad outcomes. Bill, more than most people I know, works tirelessly for that."

The Empire Center this week successfully sued to get more information from state health officials on nursing home deaths during the pandemic -- days after Attorney General Letitia James in a report found the state undercounted where those deaths occurred.

The issue has been part of a larger political fight.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has framed the issue as an attack from the right wing, the Trump administration and conservative media -- a contention undercut by Democratic lawmakers who have sought the information as well.

"It’s an important victory for all of us," said Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, the longtime Democratic chairman of the Assembly Health Committee, a lawmaker who otherwise would have deep disagreements with the Empire Center on health policy matters like single-payer health care.

"This is important data that we in the Legislature and countless New Yorkers have been demanding for months. The Health Department says it is already complying with the FOIL demand, and it should also announce it will not appeal this court decision. The Empire Center has performed an important public service."

Hammond began the push for the data on Aug. 3. At the time, he was technically supposed to be on vacation in the Adirondacks. His request was quickly stonewalled and the Empire Center would follow up with a lawsuit after weeks of delay.

The request sought data for each facility on each day, helping researchers and the public track how the pandemic over real time in different parts of the state.

The Department of Health, the largest cabinet-level department under the governor, receives FOIL requests that likely number in the tons (Hammond would blanch at this imprecision) each year. Records requests to the department have been known to languish.

"The importance of detail was illustrated by that quasi-scientific report the Health Department put out in July," Hammond wrote in an email. "Its whole thesis was based on precisely when nursing home deaths peaked in April, and comparing that to when staff infections peaked and when the March 25 memo was issued."

That study, which blamed asymptomatic visitors and staff for spreading the virus, did not review all of the known deaths in nursing homes. Meanwhile, requests by lawmakers to have more data on nursing home deaths, yet to be formalized by a subpoena, had been stymied.

New York's open records law is one of the earliest to pass in the wake of the Watergate scandal which led to a burst of good-government legislation. It's most often associated with being used by journalists, but it can be used by any member of the public. Often that will mean academics or gadflies or market researchers trying to get access to free data.

"The FOIL law has its weaknesses, which is why we still don’t have the data six months later," Hammond said. "But it forced the department to go on the record with estimated deadlines and reasons for the delay — which was revealing in itself. The fact that the deadlines kept slipping, and that the reasons given were so weak, made clear that DOH was stonewalling and had no intention of sharing the numbers any time soon."

The delays kept the story humming along, Hammond said.

"That in turn helped keep the issue in the news and put pressure on lawmakers who had publicly demanded answers," he said. "The FOIL law needs strengthening, but the ritual of publicly seeking records and being turned down has a power of its own."