Gloved and masked behind a closed curtain under hoods vented with air filters, technicians at Cornell’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center open boxes of milk samples as they work to help slow the spread of a virus infecting hundreds of cows across the country.

First discovered in March, 14 states in the U.S. have confirmed high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in livestock, and the research center has led the testing of these animals by tripling its capacity.

“We were hearing rumors that there were a high number of sick cows in the panhandle of Texas, and we knew other labs had done a lot of testing for the common diseases,” said Elisha Frye, a veterinarian and professor at Cornell University. “The veterinarian mentioned there were dead birds and cats on the farm, which made me think of HPAI.”

Frye and Diego Diel, a veterinarian and director of virology laboratory at the Animal Health Diagnostics Lab, were both authors on the study confirming mammal to mammal spread of HPAI. It has not yet been detected in New York.

Since March, the lab has tested 7,200 samples of milk from dairy cows. New York has implemented testing requirements for lactating animals going to county fairs and for cows coming into the state. The U.S. Department of Agriculture also has testing requirements for cows moving interstate.

“I think that provided some sort of barrier for introduction of the first. It seems like there’s not a lot of evidence that the virus continues to jump from birds to cattle, but it may have been a single introduction and is spreading with cattle movement,” Diel said.

Mani Lejeune, director of molecular diagnostics at the lab and co-author on the same report, said this outbreak has helped the lab expand their testing capabilities.

“Before the outbreak if you had asked how many HPAI samples can our lab handle per day, if we stretch out resources thin, we could handle a maximum of 800 samples,” Lejeune said.

Now, they can handle between 2,500 and 3,000 samples per day by automating some steps in the process.

“Although we have not reached that yet, we are well prepared to handle any surge,” he said.

The Animal Health Diagnostics Center is the veterinary diagnostics laboratory for New York and employs over 250 faculty and staff. The facility tested specimens from over 700,000 individual animals last year.

It receives funding from the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets, Department of Enviornmental Conservation and the National Animal Health Laboratory Network.

A look at the testing process

Cornell has shipped nearly 22,000 test tubes to clinics across the Northeast, and all precautions are taken when they are returned.

“We open them, we go through the samples and the paperwork. We make sure that the samples they submitted is labeled with the right IDs, after that we enter the information into the system and it generates labels for us,” receiving supervisor Esref Dogan said.

When opening up the samples, each one is treated as if it could be positive. The staff wear personal protective equipment and open the packages in a sealed room to prevent any unnecessary exposure to other employees, Dogan said.

Barcode labels are placed on the tubes in a specific location so when they go to the molecular lab, a robot can scan them.

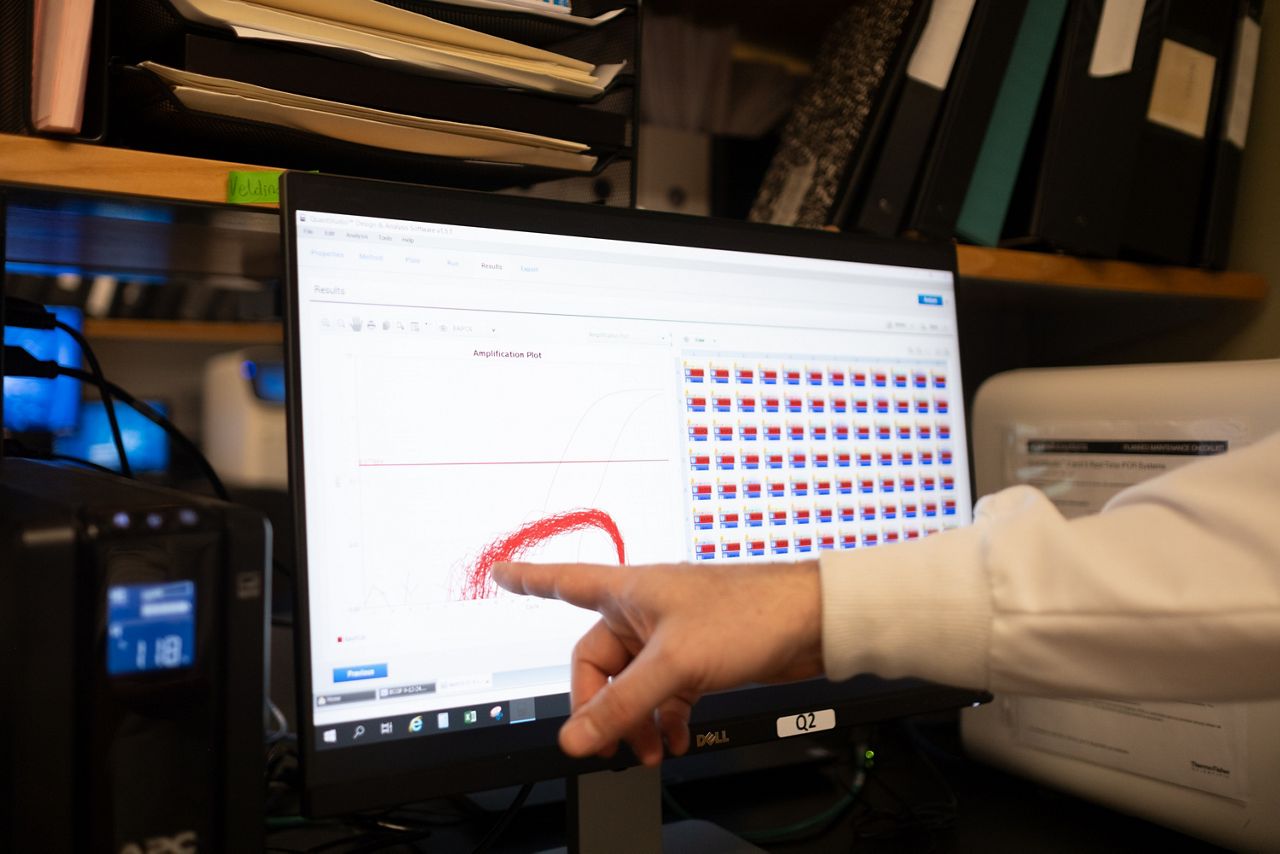

“After the barcode is read, it knows which sample is in each of these locations and so we use that same format for actually running the PCR and analyzing these samples,” laboratory manager John Beeby said.

This system helps to eliminate human errors that can occur when running hundreds of tests a week, he said. The PCR test may be familiar as it was used frequently during the coronavirus pandemic. It stands for polymerase chain reaction and is a technique used to amplify a small section of DNA.

“Polymerase chain reaction, it’s just looking for a specific DNA sequence of the pathogen of interest, so in this case, influenza,” Beeby said.

The results are then analyzed with another computer before they are interpreted by lab technicians.

Beeby said the outbreak has helped him and the laboratory staff be more prepared for larger amounts of samples.

“We wanted to be prepared for higher volumes, which is why we have these two robots that could handle maybe 2,000 probably even 3,000 samples a day. It was challenging and intense to get this up and running, but it’s definitely a much more comfortable feeling,” he said.

In the event of a ‘non-negative’ test result

New York is not among the 14 states that have seen HPAI in livestock, but just last week California reported their first positive result suggesting that the virus is still spreading.

“We cannot call an HPAI result positive. We call it a non-negative and then that sample gets referred to the National Veterinary Services laboratory in Ames, Iowa, and they would test the sample to confirm,” Olson-Damaj said.

After verifying the result, the state is notified and they implement their own procedures, she said.

For poultry that contract avian influenza, it results in rapid mortality but for dairy cattle the disease shows up first with lower milk production.

“The virus replicates mainly in the mammary gland or the udder of the affected cows resulting in severe mastitis. Mortality in dairy cows is debatable, but there is now some data coming out that indicate there is a slight increase in mortality in dairy, however, the disease is not nearly as severe as it is in poultry,” Diel said.

This means the virus is found in milk samples of cows, but consumers purchasing milk from grocery stores are not at risk.

“If consumers consume dairy products that are subjected to FDA-approved pasteurization methods, then most likely the risk is very close to zero. However, raw milk products continue to pose a risk,” Diel said.

For producers who have been impacted by HPAI, the USDA has funding available to offset the loss of that milk. Additionally, they offer funding to cover the costs of veterinary samples and improve biosecurity measures.