New York farmers have been working with state agencies to improve efficiency and safety to reduce the need for overtime hours amid changes to the threshold.

Introducing a lean management style on farms was one way that the New York Center for Agricultural Medicine and Health is using to improve efficiency.

“It relates to wanting to get things done efficiently so you’re reducing waste. Examples of waste might be transporting things too many times, or you’re having people waiting around to do work,” said Christina Day, a farm services navigator at the New York Center for Agricultural Medicine and Health.

Accuracy is another component of the training.

“You want to make sure you have as few defects in the system as possible, and you still want to maintain a good product at the end,” Day said.

In January, New York reduced the overtime threshold for agricultural workers from 60 hours to 56 hours, and this number will continue to go down over the next 10 years until it reaches 40 hours.

“I think farmers get asked a lot to do the same amount or less, one of the more recent things is like cutting the overtime threshold down, and so how do we improve employee efficiency?” Day said.

Hannah Worden, a partner at Will-O-Crest Dairy in Clifton Springs, said this has been a concern for their workers.

“Talking to our guys about it, it feels like a lot of pressure on them to do more in the same amount of time but we’re trying to help figure out how to make your job more efficient,” Worden said.

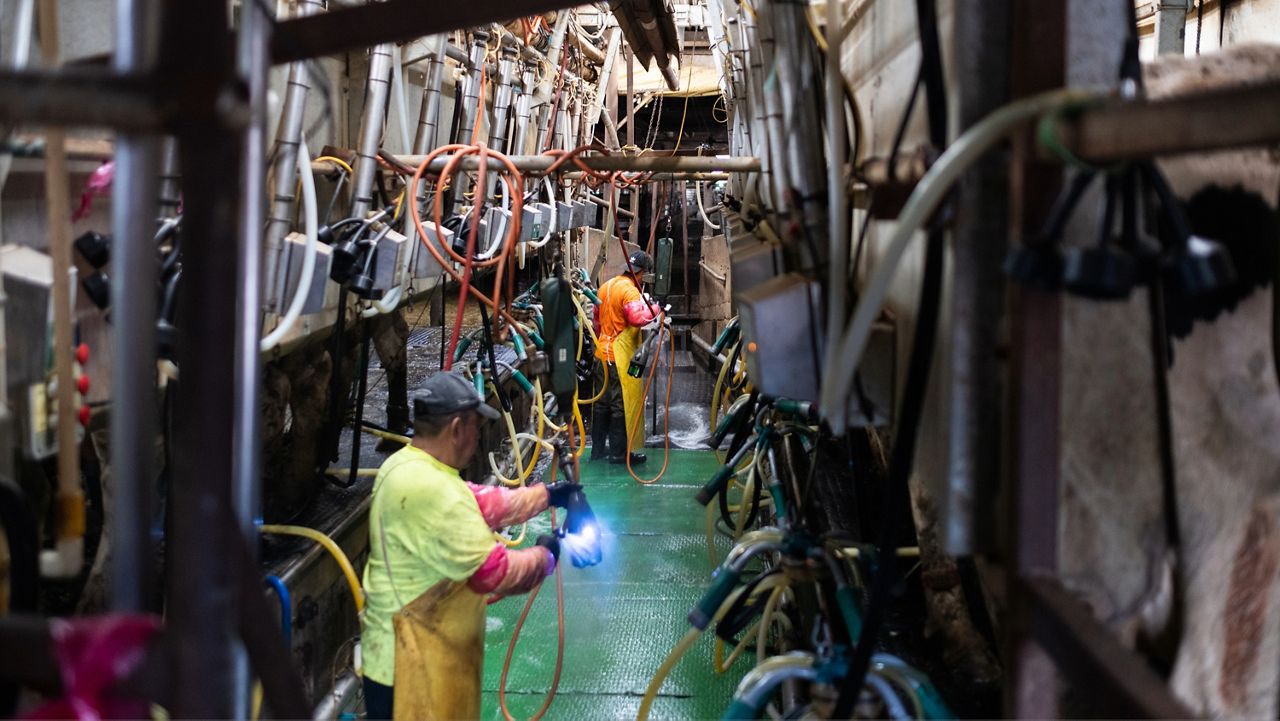

Will-O-Crest has about 50 employees and milks 2,000 cows.

“It’s just one small mistake that can have big consequences, like a slip or a fall, someone could do in an office, and it doesn’t have much of a consequence but there’s a much different consequence here,” Worden said.

Julie Sorensen, executive director for New York Center for Agricultural Medicine and Health, said the new training comes following an accident on a farm where two people were injured by a skidloader.

“We put together a plan that involves providing lean management training for farm supervisors and managers then incorporating a walk through to identify hazards on the farm,” Sorensen said.

From there, NYCAMH can provide specific training for each farm’s needs. Additionally, farms can submit proposals for safety projects.

“We were looking at our manure system and how to make it more efficient, so people had to spend less time repairing it so there’s less opportunity for accidents,” Worden said.

NYCAMH helped provide bilingual training on the different pieces to better understand the manure system. Other projects that farms have taken on include electrical upgrades and improving flooring to avoid slipping.

Farms are more likely to prioritize things that have multiple benefits rather than just one due to their tight profit margins.

“If it also has a productivity benefit or it can help engage your employees better, those are things that might be more likely to be implemented,” Day said.

Richard Stup, the director of Cornell University’s Agricultural Workforce Development Center, worked with NYCAMH to develop this training and has seen success on the farms that have implemented it.

“After that training, they saw a 30% increase in productivity and employees reported that with the system changes that they made, they had less stress at work,” Stup said.

Currently this is only being done on dairy farms, but both organizations see the potential for it to expand into other industries like vineyards and orchards.

“This is just a powerful way to bring employees together with managers and farm owners and with outside advisors to really work together to make jobs and systems on farms better,” Stup said.