More and more farmland in New York is being purchased and rented for residential developments and solar power, decreasing the number of viable agricultural acres and increasing the price of land, federal and state data show.

Karin Reeves, whose family has farmed in Baldwinsville since the 19th century, said they are constantly approached by people who want to rent pieces of their 300-acre land for solar power. The Reeves family produces approximately 5 million pounds of produce per year.

“There is a big push to use renewable energy, which I'm totally in favor of, but it’s just not the best use for prime agricultural land,” Reeves said.

New York has lost 253,500 acres of agricultural land to development between 2001 and 2016, according to the American Farmland Trust, a nonprofit that works to protect farmland. The report found 78% of those acres were converted to low-density residential. AFT’s research shows that by 2040, 452,009 acres will be lost to urban and low-density conversion.

In addition to acres lost, AFT found it would be the equivalent of losing 2,500 farms, $288 million in farm output and 7,200 jobs.

The type of land being developed matters as, especially in New York state, the quality of soil can vary. Reeves said different soil types are better than others for agricultural use such as growing crops, and using land that is lower quality should be targeted for development.

“That’s what should be used for solar, not prime agricultural land where you can grow vegetables and a wide variety of things,” she said.

According to research from Cornell University, on existing solar structures in New York, 44% of the projects were sited on crop, pasture or hay land, and 58% of solar projects were built on good quality soil or what has been defined as prime farmland.

Reeves does not fault farmers who chose to rent or sell their land to be used for solar or other purposes as they have faced financial challenges in the past few years.

“Farms are being pinched. We’ve had rising input costs, labor costs, we’ve seen record inflation,” Reeves said. “We’ve had pressure from imports. A lot of our customers can buy things cheaper from Mexico or Canada.”

The family rents out a portion of their land to a nearby farmer, who pays approximately $100 per acre, but solar companies are offering 10 times that rate, Reeves said.

“I believe it’s anywhere from $1,000 to $1,500 an acre per year, and most of these places are going to want you to sign a 30-year lease,” she said.

Sen. Michelle Hinchey, D-Saugerties, chair of the Committee of Agriculture, said an energy crisis cannot be exchanged for a food crisis.

“That is the vital element at risk of being lost when our agricultural lands are increasingly subject to aggressive development pressure,” Hinchey said.

By planning, siting and scaling renewable energy correctly, it’s possible to achieve a net-zero future, while still protecting the food system and farmland, Hinchey said.

“Failing to do so will make New York even more vulnerable to the whims of the climate crisis, and through legislation I sponsor, we can take a smarter approach to understand the all-encompassing implications of solar development for the future of our state and planet,” she said.

Hinchey has proposed a bill that would require the Office of Renewable Energy Siting to consider agricultural impacts on active farmland when siting and constructing energy facilities.

The New York Department of Agriculture and Markets and the New York Office of Renewable Energy Siting did not immediately respond to requests for comment on how the state balances solar siting with farmland protection.

Switching farmland to a solar field can happen without even needing a zoning change, said Michael Kalet, director of sales and broker for Pyramid Brokerage Company in Syracuse.

The prices for land purchased for solar or commercial use have skyrocketed due to high demand, Kalet said.

“You have seen the prices increase dramatically to the point that it’s not even on the same page as agriculturally zoned land,” he said.

Farmland for agricultural use in New York goes for about $5,000 an acre, whereas to redevelop that land for commercial use can cost $30,000 an acre or more, Kalet said.

While there is some protection for land that is zoned as agricultural use such as paying additional fees if the land is converted from farm use, Reeves said she would like to see prime farmland receive protections similar to wetland areas, which are restricted from a lot of uses.

"They [solar energy companies] claim if you put solar on farmland, it can be restored to what it was originally, but it will never be the same,” she said.

New York is one of the leading states for incentivizing the use of non-prime agricultural land for developments and solar, said Samantha Levy, conservation and climate policy manager for AFT.

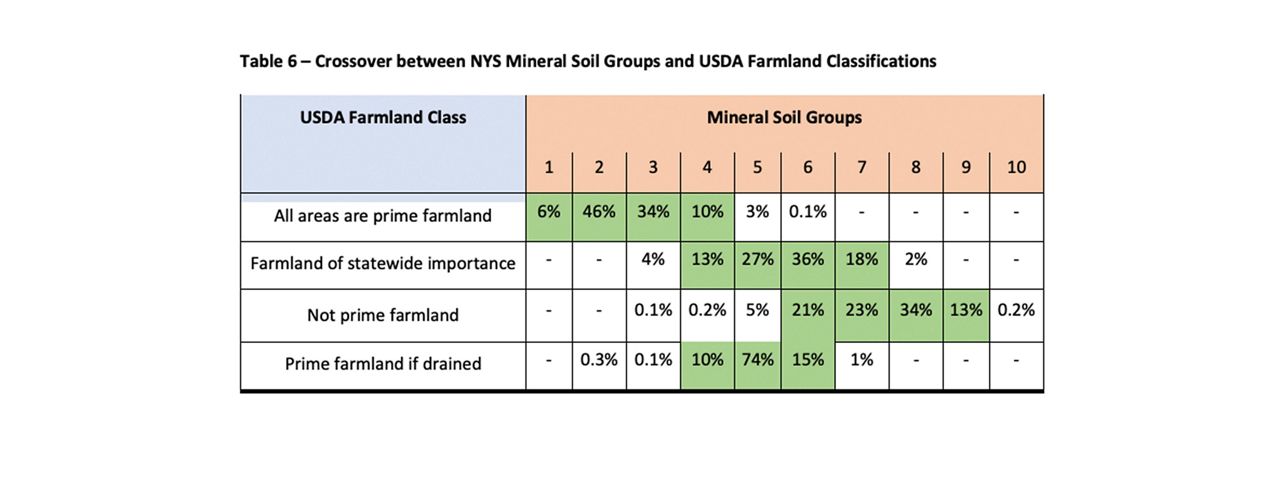

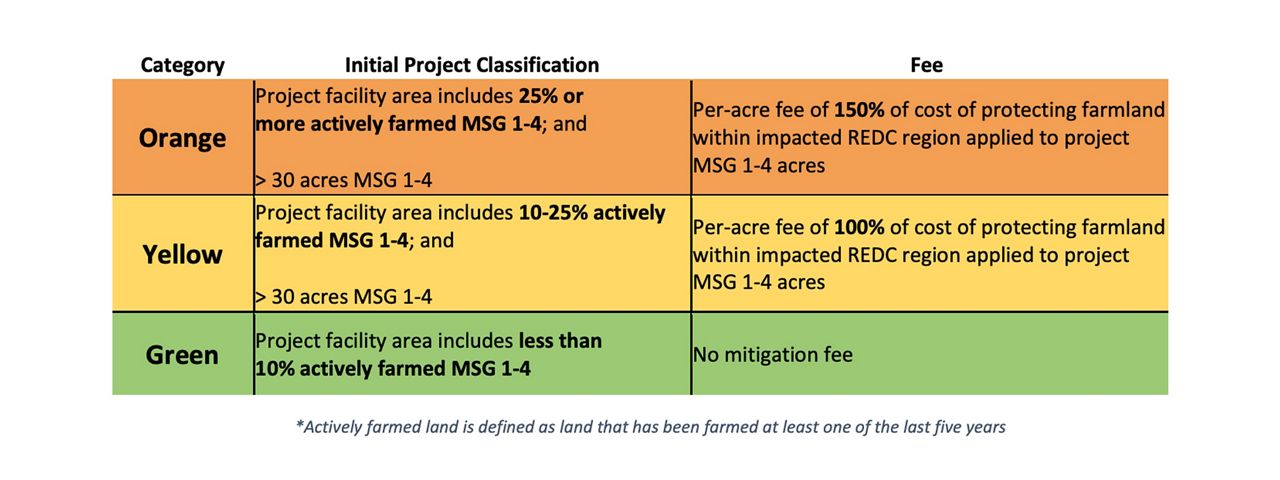

New York has a mitigation fee that they charge if land is converted out of agricultural production of the class 1 through 4 soil types, Levy said. Additionally, the New York Department of Agriculture and Markets has guidelines for topsoil use, how to bury cables and building access roads.

Levy said because the solar industry is new, there haven’t been any cases that they know of where land used for solar has come back into agricultural production, and many at AFT are skeptical that it would.

“If you’ve got enough land taken out of production in a community for a large-scale project, you’re reducing the land base available for farming. You’re reducing the base of businesses for support services, and we’ve got an aging farmer population across the country with a lack of successors so putting that land into solar then you’re not passing knowledge down to the next generation,” she said.

And the next generation has challenges of its own.

Steve Ammerman, director of communications for the New York Farm Bureau, said the lower supply and higher costs for land also impacts new and beginning farmers.

“There’s a lot of land out there, but prime land is limited. Buying farmland with really good soil types and that’s really productive, we want to make sure that we try and protect as much of that as we can,” Ammerman said.

Mikaela Perry, New York policy manager at American Farmland Trust, said they are working to create a system where renewable energy is balanced with protecting farmland.

“We want to prioritize renewable energy siting on land not well suited for agriculture and we want to safeguard the ability for land to be used for agriculture and that really gets into the heart of soil health,” Perry said.

AFT has developed its own scorecard for soil health within their smart solar siting research using the regulations put out by the United States Department of Agriculture and Cornell University.

“Developers will look for the least cost options, which often means looking to rural areas where the land values are lower, the land is flat, already clear and sunny because any additional grading of the land will cost money,” Levy said.