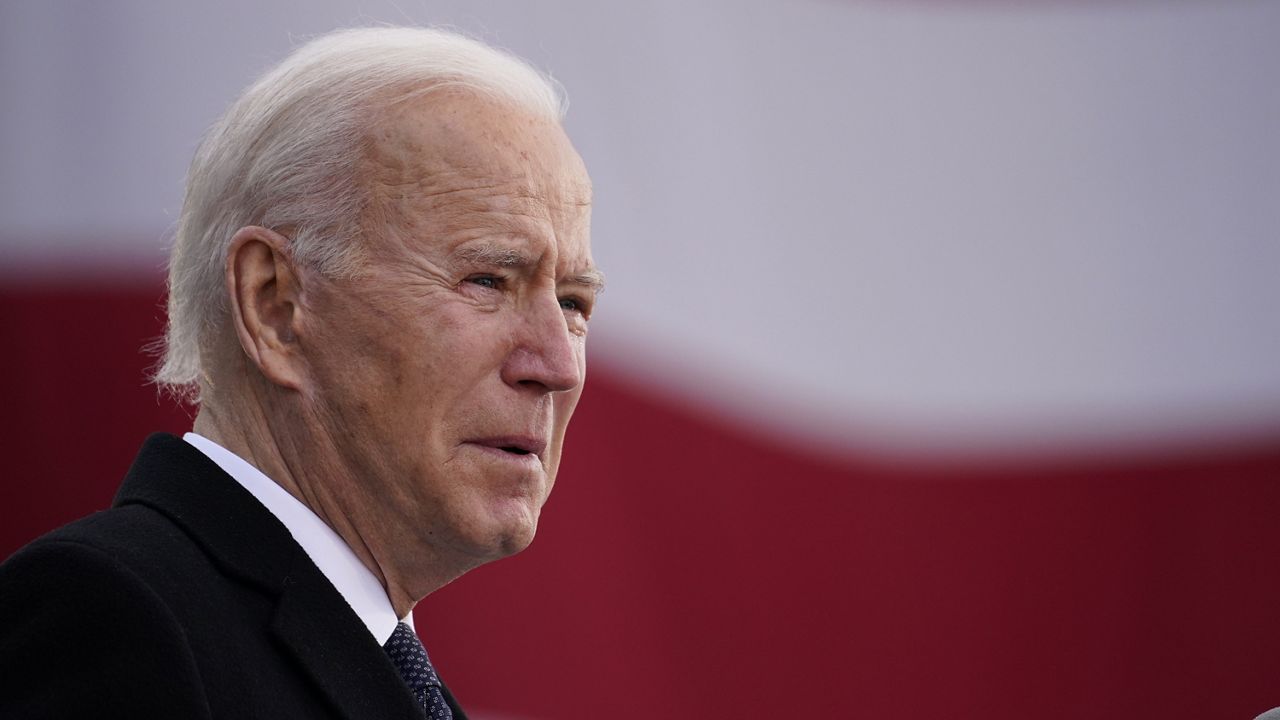

Joe Biden’s “Day One” — despite being nearly two months away — is taking shape. He’s announcing cabinet nominations and other top administration officials, and clarifying how campaign promises will morph into policy.

The to-do list is daunting, drawing comparisons to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who led the country during the Great Depression and World War II. Top among today’s challenges are curtailing the coronavirus pandemic, bolstering the economy, stopping drastic climate change, improving relations with law enforcement, and strengthening American’s ties overseas — to only name a few issues.

“It's one of the worst situations you could possibly be in,” said Terry Sullivan, executive director of the White House Transition Project and professor emeritus of political science at the University of North Carolina. “So this really is an FDR moment. Inauguration Day really is a day where the thing we have to fear most is fear itself. So he has an opportunity to step into a historical role that few presidents were ever offered.”

Perhaps most important, if unusual, Biden is intent on gaining the nation’s confidence at a time when President Trump repeatedly offers factually inaccurate reasons why fraud is behind the Democrats’ win. (Courts have overwhelmingly decided differently; the Electoral College is slated to certify the election on Dec. 14.) It’s not even clear Trump will attend Biden’s inauguration, a break without modern precedent that could magnify Biden’s illegitimacy among some Americans.

Biden’s inaugural address will assuredly aim to heal the nation’s glaring rifts

“I pledge to be a president who seeks not to divide but unify; who doesn’t see red states or blue states – only sees the United States,” he said in declaring victory Nov. 7.

Top among Biden’s priorities is responding to COVID-19, which has killed more than a quarter of a million Americans. One recent action may be symbolic, but no less dramatic: wearing a mask to his inauguration, at least before being sworn in and addressing the nation.

Biden has already assembled a task force – co-chaired by Dr. David Kessler, former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Yale University's Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, and Dr. Vivek Murthy, a former U.S. surgeon general – that will spearhead pandemic responses once he’s in office. His vaccine distribution plan would spend $25 billion on production and disbursement and calls for the vaccine to eventually be free for all Americans.

On his website, Biden outlines a seven-point plan that includes rejoining the World Health Organization; using the Defense Production Act to mass produce masks, face shields, and other PPE “so that the national supply of personal protective equipment exceeds demand and our stores and stockpiles;” and also ramping up testing under a “Pandemic Testing Board” akin to Roosevelt’s War Production Board.

Two other items on his agenda are particularly fraught: a mask mandate and a new coronavirus aid package.

The transition website says Biden would “Implement mask mandates nationwide” – but a nationwide order is of uncertain legality – and is certainly difficult to enforce. The site says Biden would encourage masks by working with local elected officials “and by asking the American people to do what they do best: step up in a time of crisis.” Biden also says he will establish a COVID-19 “Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task Force.”

As for the aid package, that requires working with Congress. Democrats will control the House of Representatives, though in diminished numbers. The makeup of the Senate hinges on a pair of special elections in Georgia about two weeks before Biden is sworn in.

Then there is Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. While President Donald Trump has said he might fire Fauci, the incoming president has indicated he will be safe in a Biden Administration.

While infection rates – and deaths – could continue to rise this fall and winter, Biden enters office in somewhat of an enviable position: clinical trials show vaccines are surprisingly effective.

But can enough doses be prepared quickly? And will enough Americans take the vaccines to tamp down the pandemic? That former question is a matter of access – the latter, again, one of trust.

Biden has said: “I’d make the changes on the corporate taxes on day one,” including lifting corporate income taxes to 28% and enacting other major repeals of the tax cut bill Trump signed into law in 2017.

But this doesn’t reflect Congress’ role in passing the required legislation – a tall order if Republicans retain control. Biden hopes to create millions of jobs across the country in manufacturing and technology, as well as restore American supply chains.

He also plans to invest in the clean energy economy – creating jobs in sustainable infrastructure and energy grids.

Biden intends to pick former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, a pivotal role in which she would help shape and direct his economic policies.

Yellen, who is widely admired in the financial world, would be the first woman to lead the Treasury Department in a line stretching back to Alexander Hamilton in 1789. Her nomination was confirmed to The Associated Press by a person who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss Biden’s plans.

As treasury secretary, Yellen would face a shaky U.S. economy, weakened by the pandemic recession and now in the grip of a surging viral epidemic that is intensifying pressure on businesses and individuals. Concern is rising that the economy could slide into a “double-dip” recession this winter as states and cities reimpose restrictions on businesses and consumers stay at home to avoid contracting the disease.

A path-breaking figure in the male-dominated economics field, Yellen, 74, was also the first woman to serve as Fed chair, from 2014 to 2018. She later became an adviser to Biden’s presidential campaign in an unusual departure for a former Fed leader that thrust her into the political arena.

Similarly, major changes to immigration law requires cooperation from Congress – and Biden has said he would on the first day of his administration send “a bill to provide for a path to citizenship for 11 million undocumented people, number one, in the United States.”

He used similar language to declare he would also send a bill to make permanent the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals protection for about 700,000 undocumented immigrants who arrived as children.

Biden is also on record as intent on reversing – or trying to reverse – key parts of Trump’s immigration plan, including establishing a task force focused on reuniting children and parents who’ve been separated; ending restrictions banning travelers from some Muslim-majority countries; and reversing construction of the wall on the border with Mexico.

Monday, he announced the nomination of Alejandro Mayorkas, a former Deputy Secretary of the Dept. of Homeland Security, to lead the agency, which oversees immigration. Biden’s statement noted that Mayorkas will be the first Latino and immigrant nominated.

Monday, Biden named John Kerry, a former Secretary of State, as Special Presidential Envoy for Climate – and highlighted the importance of climate change by placing the position on the National Security Council.

Top among Biden’s long list of environmental goals is rejoining the Paris climate accord, an agreement among more than 180 nations which seeks to limit the rise in global temperatures. The Trump administration exited the pact earlier this month, charging that it was designed to hobble the U.S. economy.

“I expect a complete change in environmental and energy policies,” Judith Enck, a former Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator in the Obama Administration, told Spectrum News.

She predicts – and Biden has indicated – he’ll return to Obama-era policies rolled back in the Trump administration on energy standards and pollution regulations, including, potentially, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where Trump is moving to allow drilling.

The goal, as indicated on Biden’s transition website: “put the United States on an irreversible path to achieve net-zero emissions, economy-wide, by no later than 2050.”

Some of these positions are seen as possible through executive action. Others, especially infrastructure spending to boost renewable energy, will require Congressional approval.

“He’s also going to have what's called a whole of government approach,” Enck says. “So it's not just the EPA in the lead, but also the Department of Treasury, Department of Labor or HUD, Agriculture. How do you get all the federal agencies rolling in the same direction on this crisis?”

Almost a year ago, a post on Biden’s Twitter account read: “We need a leader who will be ready on day one to pick up the pieces of Donald Trump's broken foreign policy and repair the damage he has caused around the world.”

The President-Elect is beginning to telegraph what that means: a deeper connection with traditional European partners, rejoining of international institutions like NATO, and tougher language – and perhaps actions – on human rights violators.

The pandemic and related economic collapse means Biden’s priorities will turn more domestic, but by naming Obama administration veterans Anthony Blinken as his Secretary of State and Jake Sullivan as his National Security Advisor, Biden is showing he will return to the kind of global diplomacy Obama practiced, including, controversially, on Iran.

In September, Biden wrote that by leaving the 2015 nuclear accord with Iran, Trump only accelerated its threat. “First, I will make an unshakable commitment to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon. Second, I will offer Tehran a credible path back to diplomacy,” he wrote.

Such a move could inflame relations with Israel and Arab states in the Persian Gulf like Saudi Arabia, which oppose returning to the deal with Tehran.