Buffalo, New York — home of the Bills, birthplace of buffalo chicken wings, and the punchline to many jokes about the weather. But some locals say the complaints are overblown. Some even say the weather is one reason to move here — even if they may have mixed feelings about word getting out. In the final installment of our three-part series, Spectrum News anchor Josh Robin visited to find out for himself.

What You Need To Know

- Extreme weather events are prompting some to reconsider the safety of the place they call home

- Experts say 6 to 13 million Americans could be forced to move as a result of sea level rise alone

- As extreme weather events become more frequent, the safest places to live may not be where you'd expect

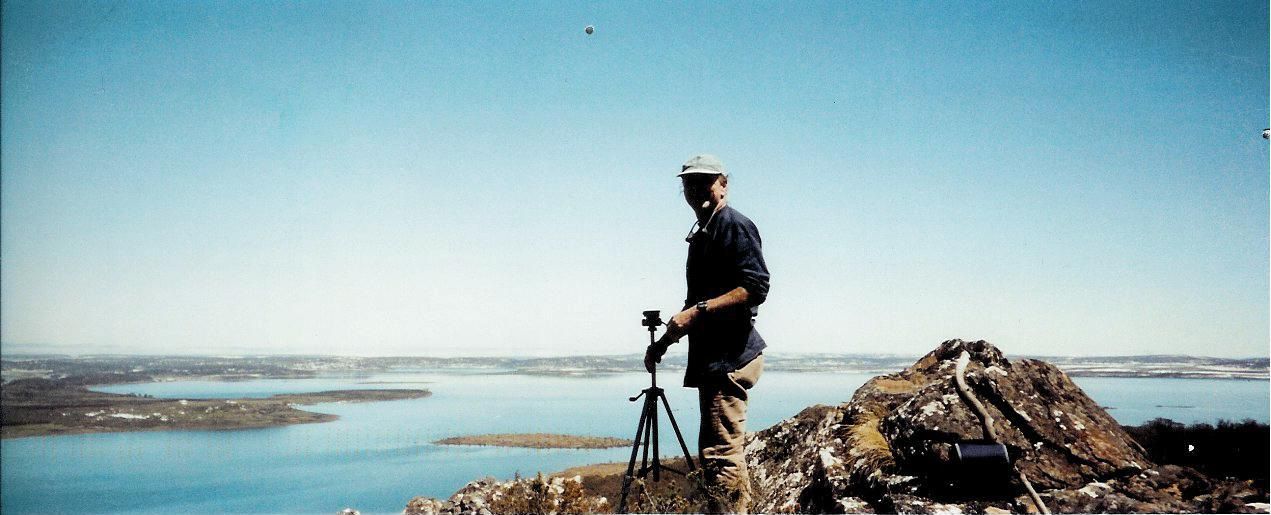

Western New York native George Besch was an early prophet of a message — that Buffalo, New York is the climate haven of the future. It’s a message he’s been preaching for over a decade.

“The migrants are going to come here. People are going to move here. Whether you want them to or not,” he said.

Besch would know. Being born and raised on a farm in Buffalo inspired his career in ecology. He spent that career traveling the world. But throughout all his projects, he saw a common thread — the climate, he realized, was changing.

Seeing so many effects of the changing climate up close, he says, got him thinking.

“How can we develop to make our society or our culture sustainable?”

He believes the first step is developing in the right places — regions that would be spared the most extreme effects of climate change.

After a lifetime abroad, he realized the best place to be was actually the place he knew best.

“We‘re nicely nestled between two Great Lakes,” Besch explained, “which does a lot of ameliorating of any climate.”

Even on the snowiest of days, he argues Western New York is the place to be.

“The horrible 91 degrees days we had here,” he said, “that’s the worst that it gets.”

Compared with the extreme weather events and heat that many other parts of the country are experiencing, Buffalo’s cold, snowy days seem far more manageable.

For decades Besch knew that the region’s climate was destined to draw people. It was time to start preparing.

The result is Designing to Live Sustainably — an organization he started to boost what he calls sustainable development in Western New York.

It took awhile, but the idea caught on. In his 2019 State of the City address, Buffalo mayor Byron Brown acknowledged the city’s unique position.

“We know that Buffalo will be a climate refuge city for centuries to come,” he said.

The announcement came after a Harvard study identified Buffalo and Duluth, Minnesota as the two places in the U.S. best suited to become receiver cities — that is, places receiving people fleeing from extreme weather elsewhere.

The designation came as a surprise to Buffalo officials, who weren’t used to such kind of talk.

“The first couple of things that people will say when you say you’re from Buffalo is, oh, is it still snowing up there?” said Brendan Mehaffy. “So we were defined in a lot of ways by our weather.”

Mehaffy is the executive director for the Mayor’s Office for Strategic Planning. That’s the department tasked with preparing for and responding to the needs of the changing population.

He remembers receiving formal notice in 2018 that Buffalo had been designated as a receiver city.

“I don’t think any of us realized how fast it would be.”

By some accounts, the migration has already begun. Hurricane Maria brought several thousand people to the region. And it’s not just individuals that are relocating here.

“The peach industry is buying up agricultural land up here to grow peaches,” said Besch, who has been watching closely for early signs of climate migration. “Winegrowers in California bought up all the land around our Finger Lakes.”

All this growth represents an about face for a city that until recently had been watching its population shrink.

Buffalo is what’s known as a legacy city — a former industrial city that has seen steep population declines in the latter half of the 20th century. That is, until now.

“We’re one of the only legacy cities, and I would say Great Lakes cities, that in the last census had the population growth,” cited Mehaffy.

That history, he said, means Buffalo is well-placed to receive an influx of climate migrants.

“Because of the decline in our population, we lost a significant amount of housing stock and in their stead is a lot of vacant lots.“

Those lots, the city believes, offer an opportunity to create new, sustainable and affordable housing stock for current residents and climate migrants alike.

But critics say it’s how you build that makes a difference.

“The problem is that American cities as they exist today, and as they are continuing to evolve, are unjust places,” said Henry Taylor, a professor of urban studies at the University at Buffalo.

He sees the potential for Buffalo to become a refuge for climate migrants but worries an influx of migrants could trigger higher housing costs, potentially displacing current residents — particularly in Black and brown communities.

“Black communities are being destroyed through what we call white reclamation of central cities,” said Taylor.

He says the city’s affordable housing plans don’t go far enough, and that without changes in laws like income-based rent caps, Buffalo will look very different.

But according to Mehaffy, the city is taking these concerns seriously.

“We recognize that with this change we do not want to displace our existing communities,” he said. “So Mayor Brown has made a commitment, and we work towards it every single day, of keeping 40% of our housing units in the city of Buffalo permanently affordable.”

City officials argue that despite the growth, they’re working to keep Buffalo’s distinctiveness.

“You can’t fake community. And it’s very organic, I think, in Buffalo, and people are starting to see that,” said Climate Action Manager Kelley St. John.

“We have a genuine character in Buffalo,” said Mehaffy, “the city of good neighbors, that I think a lot of people want to preserve.”

But like everywhere else, Buffalo faces its own weather-related threats. That makes it a potentially better alternative to other cities, but not a risk-free haven some may hope.

In a hallway at Buffalo State University, a collection of PVC pipes commemorates some of the city’s impressive snow fall totals.

“So this tube here represents the average amount of snow. We see about 94 inches in any given year,” explained Geology professor, Stephen Vermette. “The one next to it is the most snowfall we’ve ever received. And that’s a 199.4 inches, and actually, it goes through the roof.”

For many, the visuals may be startling, but for Buffalonians, all this is nothing out of the ordinary.

“The thing is, it’s always been snowy,” said Vermette.

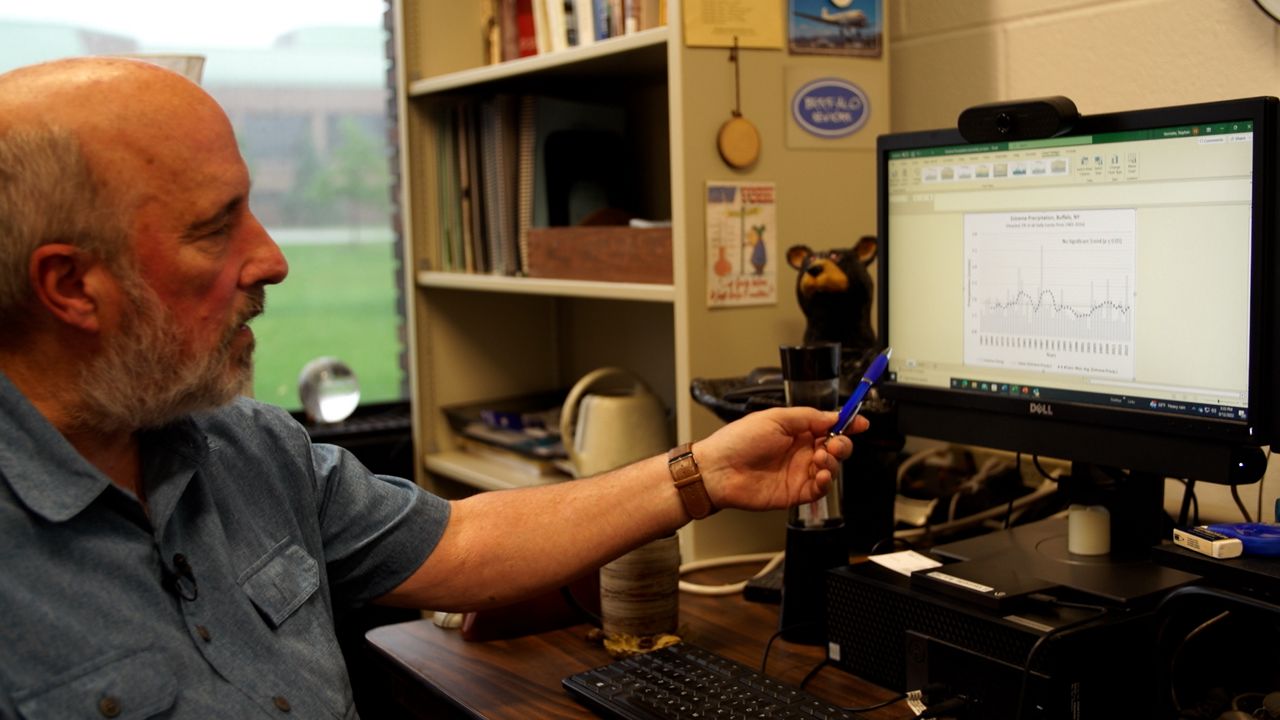

Vermette might be described as a Buffalo climate enthusiast. He’s spent years analyzing everything about the area’s weather, searching for insights into whether Buffalo will always be so snowy.

“I was seeing around the country the severe weather that’s occurring attributed to changing climate. So the question I asked was, well, what’s happening in Buffalo?”

What caught his attention wasn’t so much what he found, as what he didn't find.

“There is no significant trend,” said Vermette.

“The trend is a flat line from 1965 to 2022. There has not been an increase in heavy precipitation events.”

In other words, even though the changing climate has some places seeing heavier rain, or gustier winds, that’s not the expectation for this city on the banks of Lake Erie.

Vermette explained that, like the rest of the country, Western New York has seen an increase in average temperature.

“But it’s not equating to more severe weather, an increase in severe weather. So while people in other parts of the country are dealing with more hurricanes or more intense hurricanes or flooding or whatever, things really haven’t changed that much here.”

But why has the Buffalo region so far been spared?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” he said. “We don’t know. We don’t know. That’s the big hole in all of this.”

That uncertainty has some worried that the region’s relative immunity to extreme weather events may not last.

“In the long term in Buffalo, you know, we’re expected to see less snow, you know, certainly in a transition into rain over the next century,” said University at Buffalo professor Nicholas Rajkovich. “But until we’re at that point, we really do run the risk of having some of the significant snowfall events like we saw last winter.”

The blizzard of December 2022 was one of the worst on record. The storm lasted four days, dumping 59 inches of snow on Western New York, and leaving at least 47 people dead.

Like all extreme weather events, it’s difficult to say for sure whether climate change contributed to the severity of the storm. Vermette emphasizes storms like this are not unprecedented.

“We had the blizzard of '22; we had the blizzard of '77. We still get those kinds of storms, but nothing indicates that the intensity is increasing,” he said.

But others say the storm is proof that the region’s future is far from certain.

In truth, climate modeling experts say it is hard to predict how a warming climate will affect snowfall.

Even without the threat of more extreme weather events, Rajkovich says there are other climate impacts the region will need to prepare for.

“Certain trees that we’re used to seeing in this region are going to begin to die off as it gets warmer,” he said.

“New York’s a huge apple and grape producer. You know, all that stuff can start to disappear over time.”

The key, Rajkovich said, is preparation.

“We need to start using and actually incorporating climate projections into things like codes and standards to understand how our buildings need to respond.”

City officials say they are looking to the future, but more importantly, they’re listening.

“We went through an intense process to completely rewrite our development code infrastructure in the city of Buffalo. It’s called the Green Code,” explained Mehaffy.

St. John says they’re also speaking directly with communities to understand the effects of the changing climate and what needs to be done to mitigate them.

Experts say that a two-pronged approach is necessary to address the changes happening now, and the changes to come.

“You can walk and chew gum at the same time. You can try to mitigate what’s happening. But at the same time, you should be adapting because climate change is happening now,” said Vermette.

As climate change morphs from prediction to reality, many find it hard to not to worry about our future. That anxiety is understandable — but here’s one thing that may ease it — humans may have created this problem, but we have also shown a remarkable resiliency — the ability to adapt.

Rajkovich says ultimately, he’s optimistic about the region’s future.

“I think the message is actually primarily about hope. I think the idea that we will have, as a species, a place to go in light of climate change is actually really a hopeful and important message.”

But experts across the country say hope may be about more than coordinates on a map.

“I think that perhaps we should view this not as a challenge to find the one Goldilocks spot that may be safe,” said NOAA senior scientist, Tom Knutson.

Instead, some argue that all communities should look to the future, planning for how they will handle the changing climate.

“It’s still a useful exercise to start thinking about how we can navigate our community through these sort of changes that are already happening,” said Florida State University professor, Dr. Mathew Hauer.

Dr. Fernando Rivera of the University of Central Florida believes it’s time for a change in mindset.

“We cannot think like let me escape to this places where it’s not going to happen, but better is, let me escape to places that are ready to face those challenges.”