OHIO — A recent study showed that a satisfying intimate relationship may help in reducing chemotherapy-related cognitive problems experienced by breast cancer patients.

While general social support also helped, the association was less robust and lasting than a satisfying intimate partnership. This was characterized by fewer declines in both objective measures of cognitive setbacks and patient self-reports of subtle changes, such as being unable to multitask or forgetting lists.

Through these findings, researchers said couples' therapy aimed to enhance the quality of relationship could be helpful for partnered patients undergoing chemo.

“There are a lot of cancer treatments, but there are very few treatments for the behavioral side effects of cancer. So we need to understand how they’re happening in order to create useful interventions for the side effects,” said senior author Leah Pyter, director of the Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research at The Ohio State University and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral health in the College of Medicine. “Before this study, we didn’t understand that bolstering the intimate partnership before the patient undergoes chemo might attenuate their cognitive side effects.”

The team found that levels of the hormone oxytocin decreased significantly over the course of chemotherapy, which may give evidence of a biological mechanism that could be targeted to reduce chemo's side effects.

There were 48 participating women with breast cancer were involved in a larger study that examined links between chemo-induced inflammation, cognitive decline and disruption of the gut microbiome.

Participants took objective tests assessing verbal learning, word association, visual attention and short-term memory. They reported on changes to their concentration, memory, word retrieval and mental clarity. The measures were taken before, during and after chemo treatment.

Decreases in mental fitness did not meet the definition of cognitive impairment, but there were some changes that were considered clinically meaningful.

“It was nice to be able to test these patients before they had chemo and then again after, because people can be affected by chemo and still be within normal ranges – but for them, it’s not normal,” Pyter said.

For the study, first author Melina Seng, a senior research technician in Pyter's lab, followed up with partnered patients to assess their intimate relationship satisfaction and their social support from friends and family received during chemo treatment.

Through statistical analysis, the study showed that the more satisfied patients were in their relationship, the more protected they were from cognitive changes throughout the chemotherapy course.

“There was less decline in cognitive function for those who had a good amount of social support, but there were more associations and more enduring associations between protected cognition and the highly satisfying relationship than just with general social support,” Pyter said. “We interpreted that as an indication that the most important social relationship is that intimate partnership. There’s group therapy for chemo patients, which is social support, and this study would suggest that while that therapy might be beneficial, marital or partner therapy used in other medical contexts to improve the quality of the relationship might also be a good approach for patients receiving chemo.”

Seng hoped to find associations between oxytocin levels, cognitive function and social support, but no clear connections could be detected. The results did show that chemo affected the hormone and its receptor.

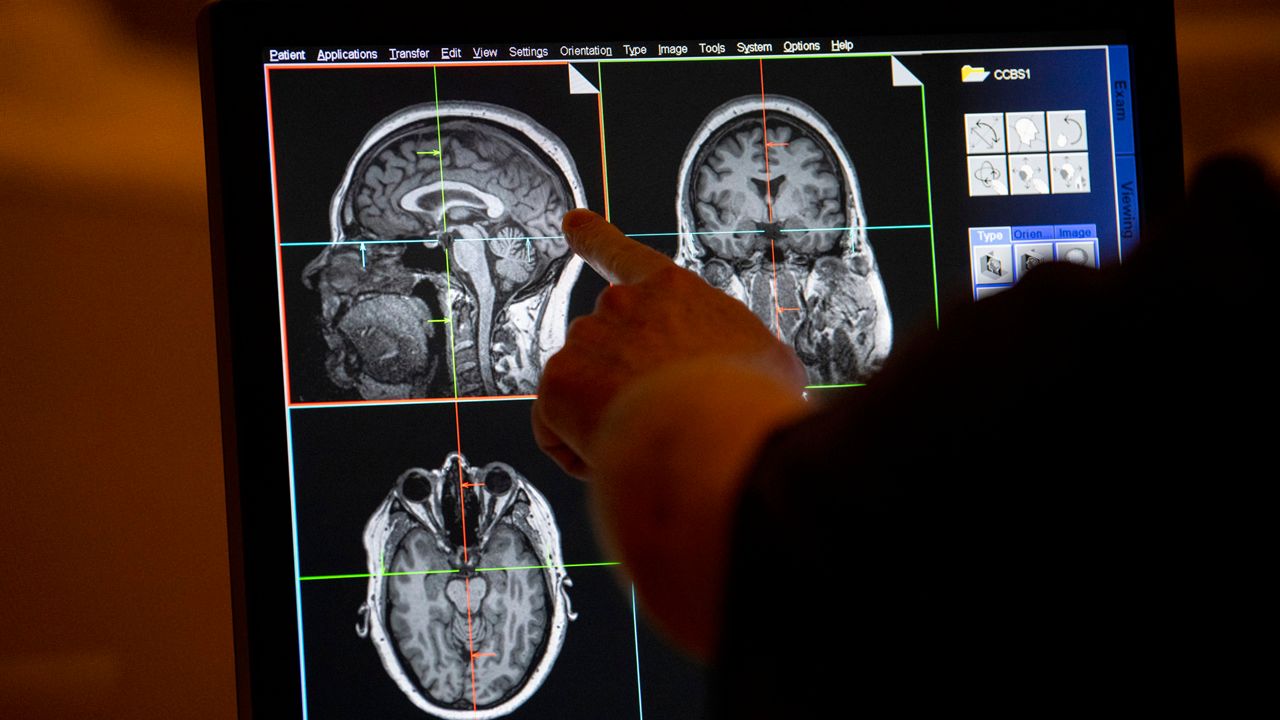

During chemo, the level of oxytocin circulating in the blood decreased significantly, but returned to baseline after treatment. This suggests that chemotherapy could affect the hypothalamus region of the brain, where the hormone is made.

“Oxytocin is well-known to play roles in social interactions and has been called the ‘love’ hormone, but it does so many other things,” Seng said. “To our knowledge, no one has ever studied oxytocin and chemotherapy before, so the fact that we saw a very strong decrease in oxytocin from pre-chemotherapy to during chemotherapy is very interesting and is something that should be investigated further.”

Both researchers said that as breast cancer survivor numbers increase, it is urgent to address the lingering side effects of treatment.

“Chemotherapy is one of the best treatments we have for cancer and for other diseases beyond cancer. It affects a lot of people and is very effective,” Pyter said. “We have more survivors, which is fantastic. Our research is focused on issues that are less well-studied, trying to make sure that survivors’ quality of life is as high as possible.”

The research was published in the journal Psychoneuroendocrinology.

)