ST. LOUIS—While bird flu concerns are mounting from New York to Hawaii as well as here in St. Louis, Washington University (WashU) reported they modified a biosensor to swiftly identify the viral pathogen for H5N1 avian influenza, or “bird flu.”

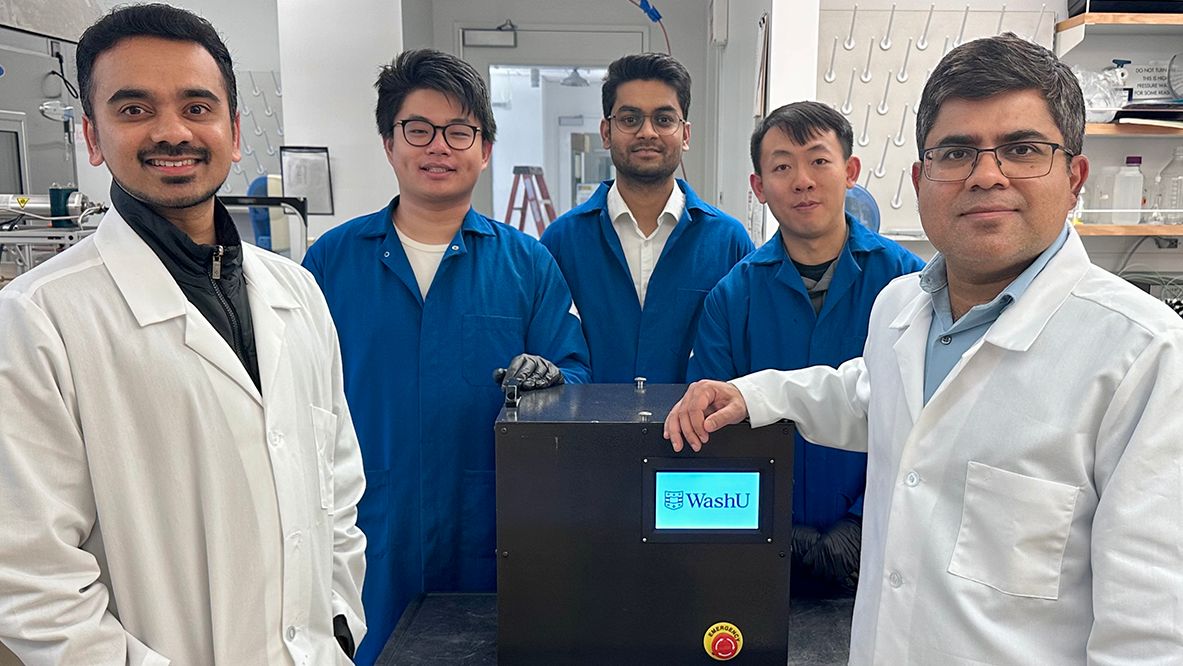

“This biosensor is the first of its kind,” said Rajan Chakrabarty, a professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering at WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering. It has the ability to offer a range of virus concentration which is a first for sensor technology.

WashU’s research on “breath sensing” was published in a special issue of ACS providing virus trackers the ability to monitor aerosol particles of bird flu. Researchers of Chakrabarty’s lab created their bird flu sensor by using electrochemical capacitive biosensors to improve the speed and sensitivity of detecting viruses and bacteria.

The integrated pathogen sampling-sensing unit is around the same size of a desktop printer according to WashU. This unit contains a “wet cyclone bioaerosol sampler” for plucking pathogens from the air. It took months of trial and error for WashU’s team to perfect the detection of H5N1.

To test animals for disease, the unit is placed at the exhaust vent of the animal’s housing. Air flowing from the housing swiftly enters the unit and is trapped in fluid lining the interior walls of the vortex. Fluid mixes with the viral aerosols. Every five minutes, samples are automatically pumped into the biosensor which seamlessly provides a range of the pathogen concentration levels detected. In a way, it’s like a breathalyzer for bird flu.

Chakrabarty stated this biosensor’s quick work gives users the opportunity for immediate action. Other more conventional testing methods often required more than 10 hours.

At the start of the research, bird flu had only transmitted to humans through contact with infected birds but that changed.

“As this paper evolved, so did the virus; it mutated,” said Chakrabarty. “The strains are very different this time.”

WashU says data on outbreaks involving animals and farms is tracked by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). Their information indicated four states including California combined for at least 35 cattle cases of bird flu in the past month.

Though made to be portable and mass produced, WashU’s biosensor is not all over yet; most farmers that suspect their animal being stricken with bird flu rely on conventional testing performed in a lab by their state’s agriculture department. If the state has a backlog, farmers awaiting answers could suffer the virus freely ravaging more livestock.

Missouri’s Department of Agriculture (MoAG) suggests practicing “good biosecurity,” to reduce the spread of diseases to livestock and flocks.

WashU’s research comes at the right time. The CDC’s website has tracked 70 human cases of avian flu since February 2024. Most of the cases are from California cattle; though, Missouri has one case from an unidentified source.

The lone death from bird flu occurred in Louisiana as an elderly patient with an underlying medical condition passed away after initially contracting the virus from birds, according to Louisiana’s health department. CDC reports zero instances of person-to-person transmission and states the risk to public health remains low.

A veterinarian in Ohio told Spectrum News that cats are susceptible to avian flu, especially outdoor cats.

The biosensor was not a quick study for WashU; researchers said their biggest challenge was at the point of pathogen detection. Their biosensor flags viruses by using single strands of DNA that bind to the viral proteins called aptamers. Researchers worked for months to make the aptamers work with a two-millimeter surface of a bare carbon electrode in detecting the pathogens.

Previously, WashU’s biosensor was used to detect COVID-19.