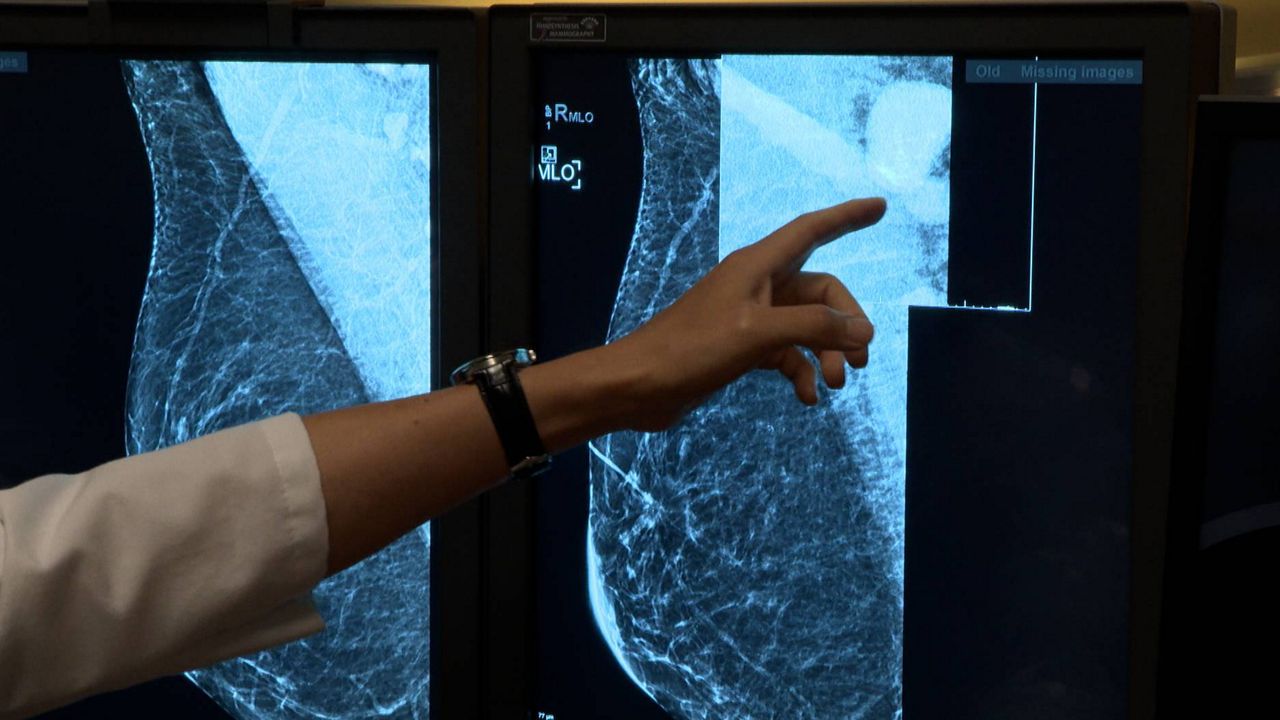

ST LOUIS – Washington University School of Medicine built an algorithm based around artificial intelligence that tracks differences in mammograms to help identify women with the highest risk of developing a new breast tumor.

“We are seeking ways to improve early detection, since that increases the chances of successful treatment,” said Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH, associate director, prevention and control, of Siteman Cancer Center, based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and WashU Medicine, and the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery. “This improved prediction of risk also may help research surrounding prevention, so that we can find better ways for women who fall into the high-risk category to lower their five-year risk of developing breast cancer.”

Past research accomplished by Colditz and Shu Joy Jiang, PhD, a statistician, data scientist and associate professor of surgery in the Division of Public Health Sciences at Wash U Medicine helped set up this risk-prediction method. These researchers learned that previous mammograms hold more than meets the human eye. Information going undetected before the new method included subtle differences in breast density over time, such as measurements of the amounts of fibrous versus fatty tissues in the breasts. The machine checked through multiple mammograms the breast density and changes in other patterns, including texture, calcification and asymmetry within the breasts.

Risk-reduction options are available including drugs such as tamoxifen, but may cause unwanted side effects. More often, high-risk women are given additional screenings or other imaging methods, such as a MRI, in hopes of identifying cancer as soon as possible.

Going into the numbers, with up to three years of previous mammograms, the new method identified high risk individuals 2.3 times more accurately than other standard methods (which uses questionnaires assessing clinical risk factors including age, race and family medical history).

Researchers trained their machine-learning algorithm with mammograms from over 10,000 women who received breast cancer screenings through Siteman Cancer Center from 2008 to 2012. The women were followed through 2020, with 478 being diagnosed with breast cancer.

Also, the researchers took their method to predict breast cancer risk to 18,000 other women who received mammograms through Emory University near Atlanta from 2013 to 2020. There, 332 women were diagnosed with breast cancer in the follow-up period in 2020.

Through the new prediction model, high-risk women were 21 times more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer over the five-year span compared to the lowest-risk group. 53 of every 1,000 women screened developed breast cancer in that time. The low-risk group, 2.6 women per 1,000 receiving mammograms. Through the old questionnaire-based methods of the same group, only 23 women per 1,000 were correctly classified as high-risk. The new prediction model identified 30 additional that were missed by the standard method.

The mammograms were done at academic medical center and community clinics to ensure accuracy of the method holding up in diverse setting. The algorithm was built with a significant amount of Black women, who are typically underrepresented in development of breast cancer risk models, says WashU. At Siteman, 27% of the tested women were Black; at Emory, 42% were Black. Accuracy for predicting worked across racial groups.

The researchers are continuing their testing on other racial and ethnic backgrounds. They’re also working with WashU’s Office of Technology Management toward patents and licensing on the new algorithm method. They intend to make it broadly available anywhere screening mammograms are provided.

“Today, we don’t have a way to know who is likely to develop breast cancer in the future based on their mammogram images,” said Debbie L. Bennett, MD, an associate professor of radiology and chief of breast imaging for the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at WashU Medicine. “What’s so exciting about this research is that it indicates that it is possible to glean this information from current and prior mammograms using this algorithm. The prediction is never going to be perfect, but this study suggests the new algorithm is much better than our current methods.”

The new study on this innovated method was published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics on Dec. 5 last year.

Colditz and Jiang are working toward founding a start-up company around the technology.