A split Kansas Supreme Court ruling last week issued in a lawsuit over a 2021 election law found that voting is not a fundamental right listed in the state Constitution's Bill of Rights.

The finding drew sharp criticism from three dissenting justices on the high court. The Associated Press looks at what the ruling might mean for Kansas residents and future elections.

The ruling itself is wide-reaching, combining different lawsuits at various stages of litigation that challenge three different segments of a 2021 election law passed by the Kansas Legislature. It was a lawsuit challenging a ballot signature verification measure in which a majority of the high court found there is no right to vote enshrined in the Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

The measure requires election officials to match the signatures on advance mail ballots to a person’s voter registration record. The high court reversed a lower court’s dismissal of that lawsuit and instructed the lower court to consider whether the measure violates the equal protection rights of voters. But four of the court's seven justices rejected arguments that the measure violates voting rights under the state's Bill of Rights.

The decision was written by Justice Caleb Stegall, who is seen as the most conservative of the court’s seven justices, five of whom were appointed by Democratic governors.

Stegall dismissed the strongly-worded objections of the dissenting justices, saying there is not a “fundamental right to vote” in Section 2 of the Bill of Rights, as the groups had argued.

The dissenting justices said that ignores long-held precedent by the Kansas Supreme Court. Justice Eric Rosen said “it staggers my imagination” to conclude Kansas citizens have no fundamental right to vote and called the majority opinion a “betrayal of our constitutional duty to safeguard the foundational rights of Kansans.”

Justice Melissa Taylor Standridge called the decision troubling, with far-reaching implications, and that the ruling “defies history, law, and logic and is just plain wrong.”

“For over 60 years, this interpretation of section 2 has been our precedent,” she wrote. “Without even a hint that it’s doing so, the majority overturns this precedent today.”

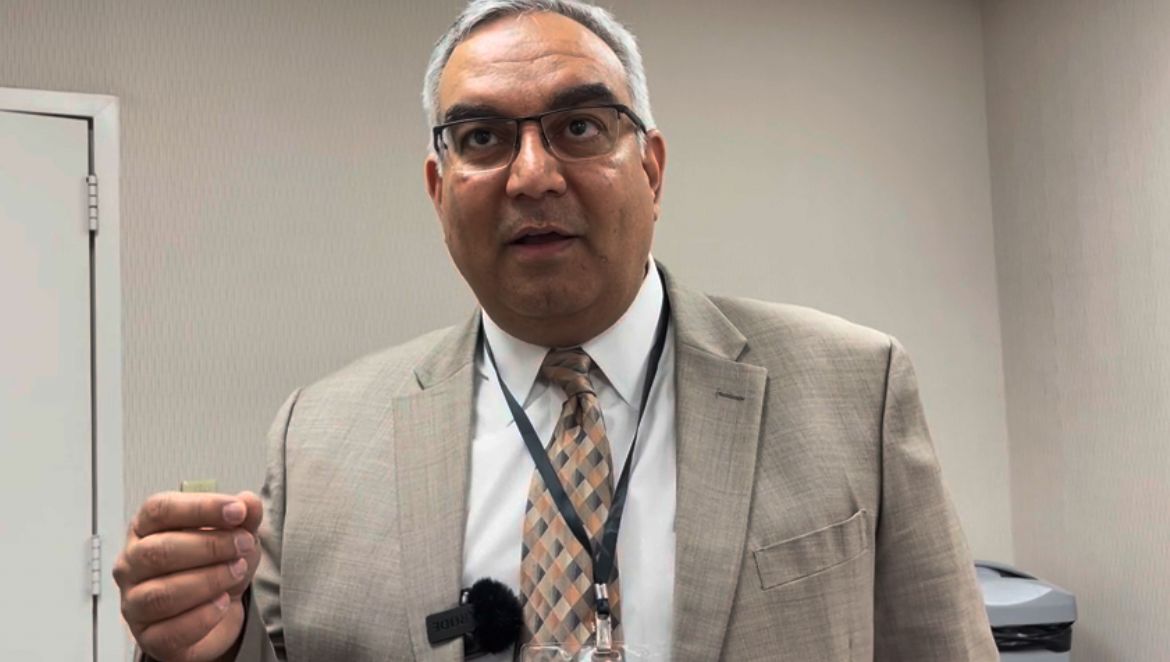

A determination that voting is not a fundamental right could embolden state lawmakers to push for further restrictions on advance voting and mail-in ballots, said Jamie Shew, election officer for Douglas County — Kansas’ most populous county.

The constant changes in election law are also confusing not only to election officials, but to voters, Shew said.

“I’ve had two voters who came in this morning, and they’re like, ‘Well, I read the paper about signature verification. Is my signature going to get tossed out?’” he recalled. “They were really nervous about it.”

Election laws had been fairly constant since the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act by Congress, Shew said. But that changed in 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court tossed out a key provision of that act, he said.

“Since then the rules just keep changing,” Shew said. “And I think our job is making sure that voters not only don’t get confused, but also don’t get frustrated and just stop participating.”

The Republican-led Legislature passed a raft of election law changes in 2021 over Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly’s veto amid false claims by some in the GOP that the 2020 presidential election wasn’t valid. Since that election, there have been lawsuits over voting across the country, and partisan election law battles have continued in high-profile states like Georgia, Arizona and Wisconsin. Fights for election advantage are also being waged in smaller states like South Dakota and Nebraska.

Shew said he and other election officials will focus on meting out the state's voting laws fairly and helping make sure the public understands them.

Justice Dan Biles said in his dissent that courts must insist that the signature verification requirement — if it survives the lawsuit against it — is handled reliably and uniformly across the state. That includes analyzing the procedures for how a mismatched signature is flagged, how a voter is notified of the mismatch and whether the voter is given a reasonable opportunity to cure the problem.

“The Kansas Constitution explicitly sets forth—and absolutely protects—a citizen’s right to vote as the foundation of our democratic republic,” Biles wrote, “so it is serious business when a government official in one of our 105 counties rejects an otherwise lawful ballot just by eyeballing the signature on the outside envelope.”