ST. LOUIS, Mo. — When one local school district banned Toni Morrison’s book The Bluest Eye last month, Heather Fleming felt sad, angry, and concerned for “the future of our schools and our children.”

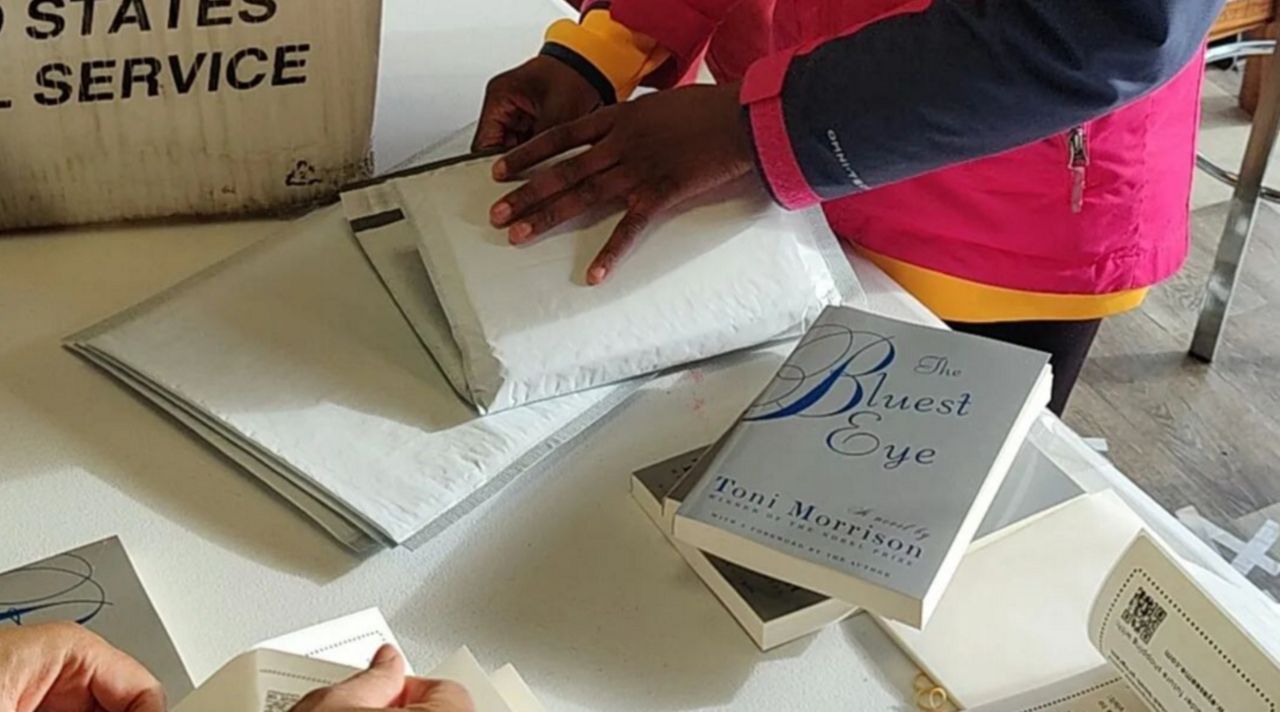

Then she got to work. A week after the Wentzville School District removed the classic novel and several other books from its libraries, Fleming partnered with Eyeseeme, an African American children's bookstore in University City, to start The Banned Book Project.

Nearly a month later, they’ve distributed hundreds of free copies of The Bluest Eye and raised $28,000 to continue their mission in the months ahead.

“This is our way of rebelling against the idea that there's a problem with Black and brown people speaking their reality and their truth through literature,” Fleming said.

A former English teacher, Fleming said she's watched in recent months as several districts in the area have considered removing books from circulation. According to a report from St. Louis Public Radio, at least three other school districts have faced challenges to books this school year.

Among the books drawing the ire of some parents are Black Girl Unlimited, a coming-of-age novel that deals with drug abuse and depression, and All Boys Aren't Blue, a memoir about growing up as a gay Black man in America. The Bluest Eye, which was published in 1970, deals with a young Black girl’s struggles with racism and sexism during the Great Depression and includes depictions of domestic violence and rape.

Fleming saw a pattern. “The thing that we noticed is that those books all seem to have one thing in common — they were written by or about people from historically excluded groups,” she said.

Reading these types of books serves a vital purpose for children of color, Fleming said.

“Students need to see books that are both a mirror and a window and too often the experience of children of color is that it's always a window into the dominant culture, but rarely a mirror into their own culture,” she said.

Fleming is not alone in her opposition to the Wentzville School District’s book bans. Earlier this month, the ACLU of Missouri sued to stop the banning of eight books in the district.

“School boards cannot ban books because the books and their characters illustrate viewpoints different of those of school board; especially when they target books presenting the viewpoints of racial and sexual minorities, as they have done in Wentzville,” stated Anthony Rothert, Director of Integrated Advocacy of ACLU of Missouri, in a press release.

Ironically, the ban on The Bluest Eye may have increased the number of people reading the book in St. Louis. Fleming said the response to The Banned Book Project has been overwhelming and that requests for books now out pace the money raised by the group.

“We had a TikTok influencer that found out about our story,' Fleming said. "We ended up with, like 1500 requests in one day."

In March, The Banned Book Project will expand its selections. For elementary school students, they'll offer Ron's Big Mission, a picture book about Ronald McNair, who experienced racism as a child in South Carolina and grew up to be an astronaut. He died in the 1986 Challenger explosion. For older students, they'll offer Stamped, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi's look at the legacy of racism in America, and All Boys Aren't Blue.

Fleming said her hope is that there is soon no longer a need for The Banned Book Project and it can change course to a different kind of book program. "But for the time being," she said, "there's a need to be addressed and we're trying to address it."