KIRKWOOD, Mo.– Liz Gibbons sees the Missouri River Runner train route as more than just a mode of transportation. She views it as a gateway to opportunities for residents and communities across the 283-miles of track between St. Louis and Kansas City.

What You Need To Know

- The Missouri River Runner is a daily trains that transports passengers between St. Louis and Kansas City

- In early January, the schedule went from two daily round trips down to one

- Critics of the decision say the train is now less reliable for passengers and is affecting tourist businesses along the 10-station route

- Rail advocates are asking state officials for $2.5 million in the next state budget to return the route to two daily trips

For years, business travelers, tourists and college kids traveling home to visit mom and dad have used the state-sponsored, east-to-west Amtrak service as a way to get to communities across Missouri. The twice-daily round trips made it an affordable and convenient option, according to Gibbons, a city council member in Kirkwood, one of the cities located along the line.

However, when the state legislature passed the budget last year they only provided enough to fund the second daily trip for six months. As a result, beginning Jan. 3, River Runner service got slashed in half, going down to one round trip service in the day – a trip from Kansas City east in the morning and a return trip from St. Louis in the afternoon.

Patrick McKenna, director of the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT), said lawmakers told the department not to go into debt for Amtrak service, according to a report from the Associated Press. He’s quoted in the piece as saying running two routes from January to June would have cost an estimated $2.5 million.

Rail advocates and community leaders like Gibbons fear the change could affect the usefulness of the rail line. They are lobbying the state legislature to include the money in their fiscal year budget in order to reinstate the second daily trip.

The River Runner budget for Fiscal Year 2022, which runs from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022, is $10.85 million. It will require about $2.5 million to make that second route happen. Unless there’s a supplemental payment in the coming days, the earliest it could return is July 1, 2022.

“When we have two daily round trips, there's the opportunity to go back and forth on the same day for many other communities,” Gibbons said. “Losing this has meant that people have to drive or people who can't drive or don't have a car can't get to places without spending the night.”

Gibbons is a member of the Missouri Rail Passenger Advisory Committee, or MORPAC. It’s an all-volunteer organization that advocates for rail passenger service across the state.

The group recently appeared before the Missouri Highways and Transportation Committee to seek funding for River Runner operations in the next fiscal year, as well as supplemental funding to restore the second train this year.

Other members of MORPAC include former State Sen. David Pearce and Tammy Bruckerhoff, director of Tourism and Economic Development for the city of Hermann.

For supporters, the train isn’t just about getting from place to place; it’s about investing in communities. Many of the cities surrounding the 10-station line rely on dollars earned from tourism and day trips from the River Runner.

“The more convenient it is for potential riders, the more people will use it,” Pearce said. “If you end up having to stay overnight in Jefferson City or Kansas City when visiting because you took the train and you live in Sedalia and Warrensburg: are you going to do that? No, you're going to get in the car and drive.”

MoDOT data shows that users of the River Runner spend an estimated $21.8 million on hotels and more than $25 million on food each year. That spending supports direct, indirect and induced economic benefits of more than 800 jobs that pay $30 million in labor income and $86 million in economic activity. It also includes $11 million federal state and local tax revenue.

The Kirkwood-Des Peres Area Chamber of Commerce, which represents 500 businesses and more than 1,100 members, supports expanding the train’s schedule.

“Only having one train per day cuts the availability and flexibility of options for travelers,” Bruckerhoff said. “What could have been a day trip with the availability of two trains, is now a driving trip, or no trip at all. This lack of travel negatively impacts our businesses and attractions.”

Prospective tourist groups already have canceled day trips to Hermann – which is known for its shops and wineries – because they wouldn’t be able to take the train back the next day, she added.

MoDOT said 172,555 passengers rode the Missouri River Runner in 2018 with an average fare of about $32.47. That fare price is also important because if you are unable to drive, it’s pretty much the only public transportation option to some places like Jefferson City, Pearce said.

Warrensburg is about 50 miles east of Kansas City. It’s right on the River Runner line and serves many of Central Missouri University’s 10,500 students, Pearce added.

“It’s extremely important. We have a lot of students from St. Louis and that's their only means of transportation to get home,” he said. “We also have a lot of international students and of course, no international students have a vehicle and so their only way to get to Kansas City or St. Louis or to the world is through Amtrak.”

The train is more than just an economic boon or a means of transportation. For cities like Kirkwood, it’s a part of the community’s culture.

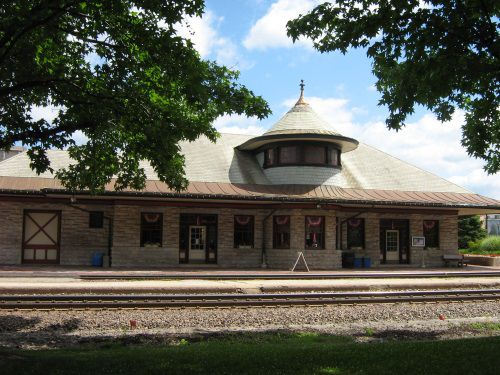

Built in 1893, Kirkwood’s train station is one of the city’s most enduring and beloved buildings. It’s the same site as the city’s first railroad depot erected in 1853, the year the Kirkwood Association purchased 240 acres of land for a planned residential community along the route of the new Pacific Railroad, about 13 miles west of the City of St. Louis. The Association named the new town “Kirkwood.”

In 2002, Amtrak nearly closed the station as part of cost-cutting efforts. Not wanting to lose the downtown icon, the city of Kirkwood bought the building. It continues to serve as an Amtrak station and doubles as a visitors' center, staffed by a group of volunteers.

Gibbons doesn’t see closure of the train station as an immediate risk, but changing the schedule affects Kirkwood’s quality of life. Train ridership has already started to decline since the start of the year, and she expects that trend to continue until a second trip is added.

MoDOT acknowledges the logic of having two daily trips.

“It’s a significant loss to drop from two trains down to one,” McKenna said. “It’s more than just cutting it in half because the trip just doesn’t work as well without the options of going and returning on the same day.”