The company hoping to build a large-scale fish farm in Jonesport recently received its first shipment of yellowtail kingfish from the Netherlands, an effort to ramp up production in anticipation of receiving final permits.

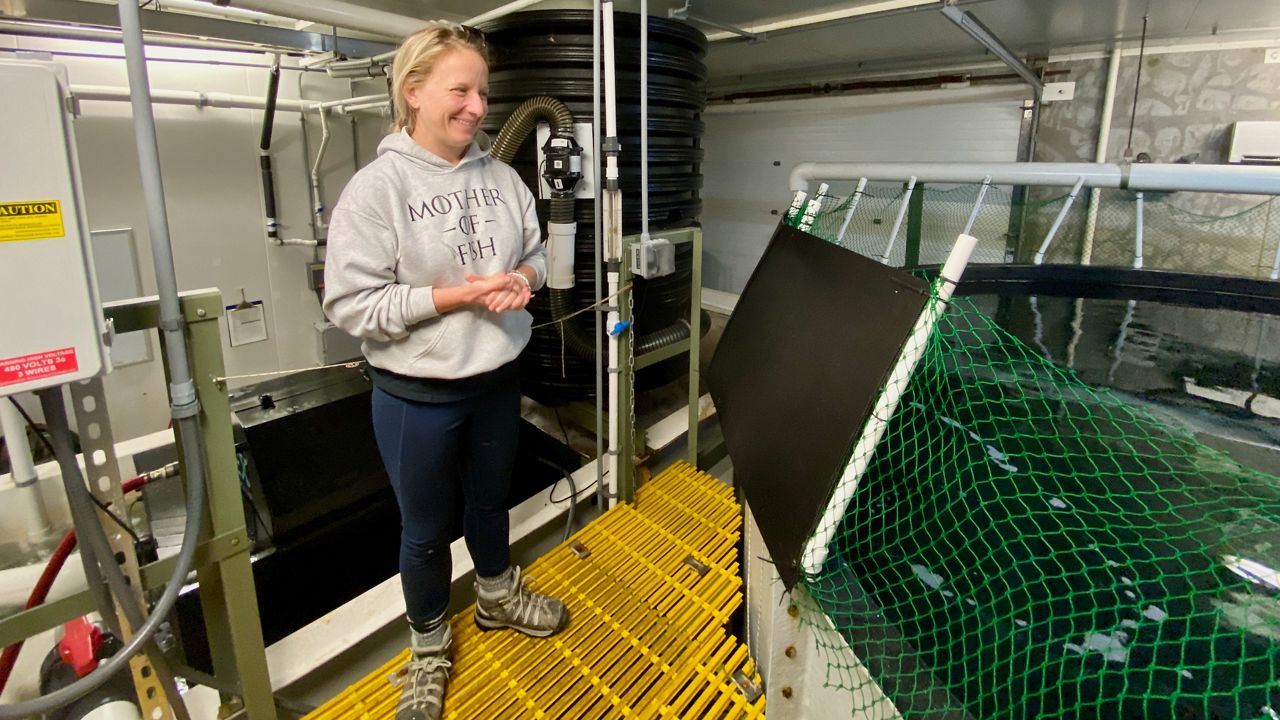

“When you’re planning a big facility, getting fish ready ahead of time is critical,” said Megan Sorby, operations manager for Kingfish Maine, the American branch of the company owned by Kingfish Zeeland in the Netherlands.

As they await permission to build a new facility on 93 acres in Jonesport, the company is leasing space at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin. During a tour last week, Sorby pointed out the tank of yellowtail kingfish that were no larger than a thumbnail when they first arrived on May 10.

Called fingerlings, they are currently in quarantine because of their recent arrival from overseas. And even before they could be shipped to the U.S., the company sent scientists to the Netherlands to test the stock, she said.

Before the company can begin construction on a permanent home for the fish, it needs a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers and approval from the Jonesport Planning Board. In recent months, residents have started asking questions about the project and the president of a group called Protect Downeast said Friday that the company is shrugging off opponents.

“The choice to bring in fish before (the company) has a local permit is clearly disregarding our community,” said Chris Smith, a lobsterman and scallop harvester. “Over 230 marine harvesters in Jonesport and surrounding communities have signed a letter stating their opposition to the project. Local voices still need to be heard and our community will not be run over by a foreign company that has deep, deep pockets.”

The company plans to build a land-based fish farm on Dun Garvan Road with structures that would total about 573,500 sq. ft. The recirculating aquaculture system would draw water from Chandler Bay, filter it for use in tanks and then discharge up to 29 million gallons per day of treated wastewater back into the bay.

Following a state review, the company received a five-year permit to allow the discharge into the bay, with the Department of Environmental Protection finding that the project will not lower the water quality below its current classification.

If all goes as planned, the company hopes to break ground by the end of the year and have fish on-site within 18 months. It will take three years and an estimated $100 million to build the project, which will employ between 70-100 people.

At an aquaculture conference in Portland last month, Sorby said she believes when the factory is up and running residents will realize that they are a good fit for the local lobstering and fishing communities.

“There’s a lot of synergy to be had with the existing businesses that are going on,” she said. “Lobstermen have to truck their product just like we would to get to a processor or just to market. Can we share that infrastructure? Can we share those trucking companies?”

In addition, the company is testing to see whether its fish can be used as bait by lobstermen and it hopes to find a way for waste to be used to produce biogas.

In the next several months, the company plans to bring in larger yellowtail called “subadults” to further build its stock. It takes three years for the fish to reach sexual maturity to produce eggs.

Yellowtail kingfish is commonly used in sushi but can also be baked like other white fish, Sorby said. The company’s fish can already be found in Whole Foods stores, which stocks yellowtail from the Netherlands.

Like other companies planning to start large fish farms in Maine — including Nordic Aquafarms in Belfast and Whole Oceans in Bucksport, both of which plan to grow salmon — Kingfish Maine is looking to tap into major nearby markets in Boston and New York.

A fourth proposal for an industrial salmon farm off Bar Harbor is on hold following a state Department of Marine Resources decision last month to stop reviewing an application from American Aquafarms. The state said the company had not identified an acceptable source for its eggs, which means the company will have to start from scratch with new applications if it wants to open a facility in Maine.

In Jonesport, Sorby and other company officials have held meetings in recent weeks to try to answer community concerns. She said the company is not only required to maintain the quality of the water in the bay, but it has a vested interest in doing so.

“If the bay is polluted, it will kill our fish,” said Tom Sorby, who works with his wife Megan as operations managers. “If we want to make money, we need to protect the bay. I need the water to be good.”