Spring tick season is well underway in Maine, driven by another in a series of relatively mild winters that are in line with the trends of climate change.

The Tick Lab at the University of Maine has received more than 400 ticks for analysis so far this season, a relatively high number that began to pick up in mid-April, said coordinator Griffin Dill.

He said this past winter didn’t have enough deep cold to really put a damper on overwintering ticks, while the extended snow cover in much of the state helped insulate them in the ground.

Maine and New England will see more winter precipitation and milder, though more volatile, winter temperatures as fossil fuel use causes the planet to warm. The region has already warmed a few degrees Fahrenheit and lost about two weeks of winter since the 1800s, with accelerating change concentrated in the past few decades, according to climate scientists.

In general, Dill said, these trends are helping lengthen the tick season on both ends of winter, causing ticks to remain active into December and re-emerge earlier in April as winter condenses.

“It really benefits the ticks overall, having that kind of shortened warmer winter,” Dill said. “They’re able to survive the winter easier, and they’re now afforded a much greater length of time in order to find a host.”

It means more risk of ticks and the pathogens they carry for humans and other animals. Dill said spring is the period where ticks that didn’t find a host in the fall, but survived the winter, will be looking for a host again. Tick activity will continue through the summer, slowing slightly when the weather is most hot and dry, before resurging to its highest annual levels in the fall months.

“As far as pathogens go, the deer tick or black-legged tick is really public enemy number one here in Maine,” Dill said. These ticks spread Lyme disease and all other infections of concern.

Dill said Maine saw a sharp uptick in dog ticks last year, but that species doesn’t transmit any known pathogens in this region – “so really they’re more of a nuisance species,” he said.

The third species of concern is the lone star tick, which transmits a pathogen that can cause a red meat allergy. It’s found only occasionally in Maine with no established populations, Dill said, but it is on the rise in other parts of New England. “It’s probably unfortunately only a matter of time” before it gets established in Maine due to changing migration patterns for wildlife, he said.

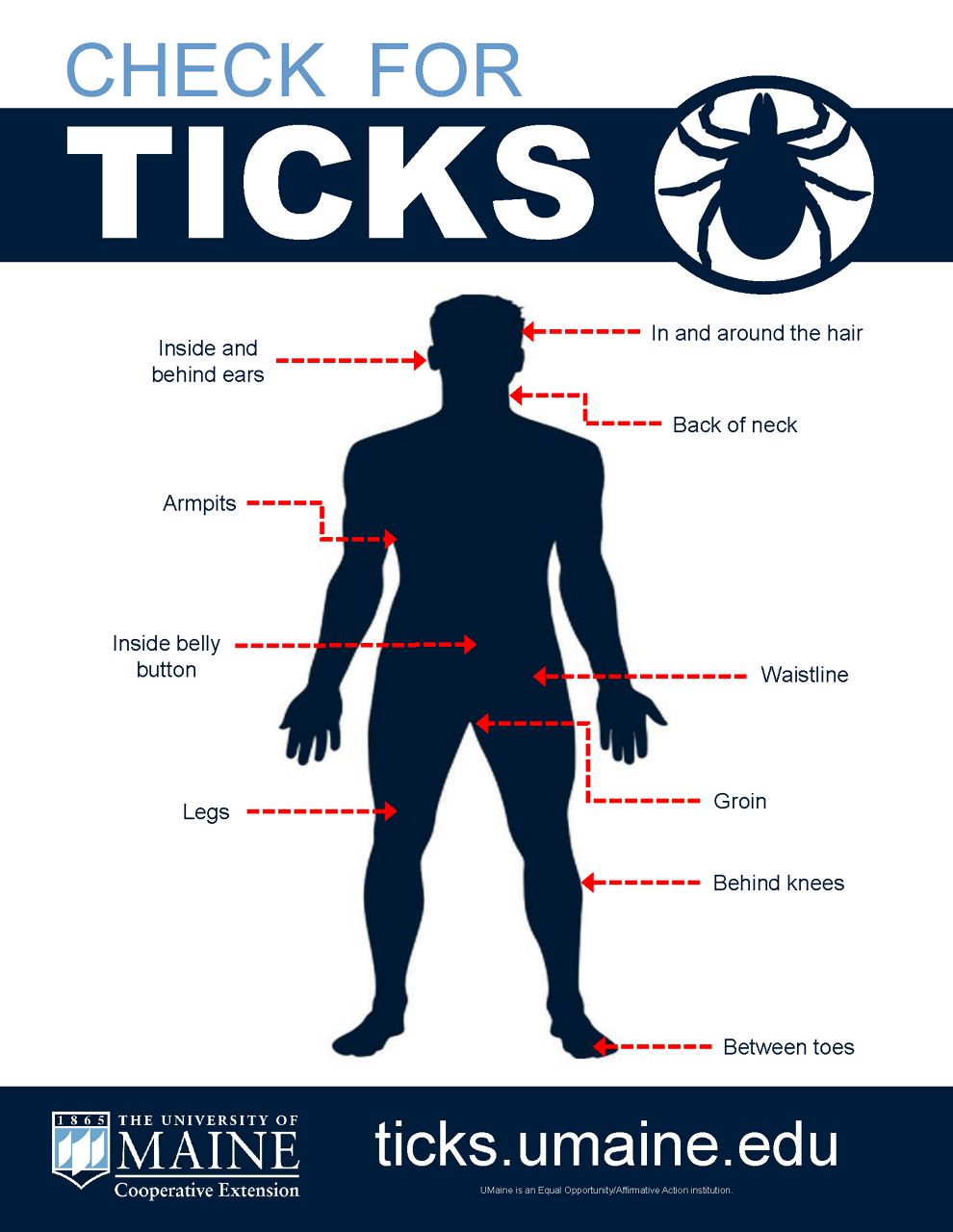

It means that now is the time to begin using tick and insect repellents, dressing in long sleeves and pants while outside and conducting frequent tick checks on people and pets, he said.

“It’s important to be mindful of ticks almost year-round at this point,” Dill said. “I think people generally associate tick season as summer, when in reality it’s early spring all the way through late fall, and in some cases we can and do see ticks pop up in the winter if conditions are right.”

He said it’s also crucial to be mindful of ticks not only during outdoor recreation like hiking or hunting, but also while doing “mundane” or “minor things around the yard” – even tending to a compost pile, playing with the dog or getting mail from the end of the driveway.

“Taking some precautions and getting in the habit of doing tick checks after being outdoors is really kind of our best bet for minimizing our exposure to ticks and tickborne disease,” Dill said.

If you find a tick on your body or your pet, remove it quickly and carefully – the UMaine Tick Lab offers instructions here. The removed tick can be sent to the lab for analysis or provided to your doctor if you are concerned about infection.

A Lyme disease rash typically, though not always, shows up as a red ring or bullseye within three to 30 days of a tick bite, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.