The best-selling author of two books on the nation’s opioid crisis urged Maine government leaders and recovery service providers Wednesday to consider using county jails as a place for aggressive treatment for those with substance use disorder.

Sam Quinones, a journalist and author of “Dreamland” and “The Least of Us,” said research he conducted in one Kentucky county showed that jails can successfully help people recover from addiction. And he warned that deadly drugs that continue to flow into the U.S. from Mexico means that any drug use can turn deadly at any time.

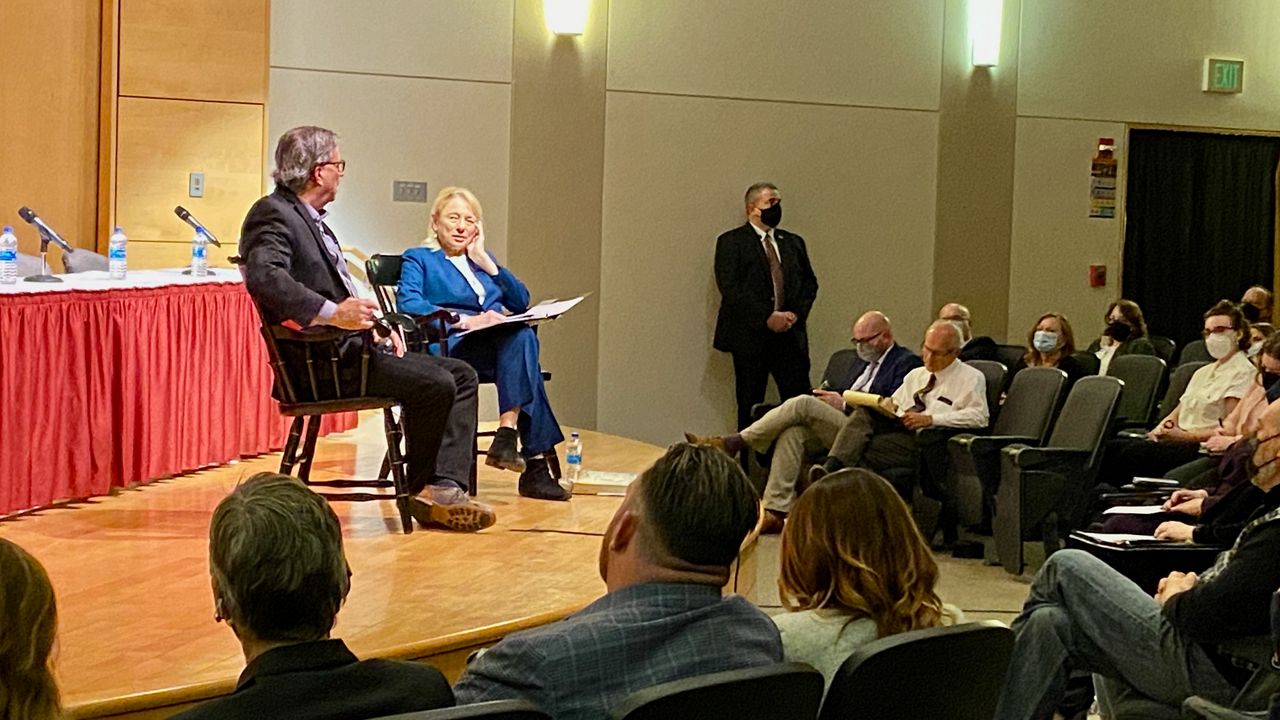

“The streets of America are filled with mass die off,” he said during a policy discussion at the University of Southern Maine. “There is no such thing as a long-term fentanyl user on the streets today. It just doesn’t exist.”

In Maine, 636 people died of drug overdoses last year, 77% of which were connected to fentanyl, according to the governor’s office. The number of deaths is up 23% from the previous year and nationally, 100,000 Americans died of overdoses from April 2020 to April 2021, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The governor’s office organized the event Wednesday as a precursor to the 4th Annual Opioid Response Summit set for July 11 in Bangor.

Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat sworn-in to office in January 2019, conducted a question-and-answer session with Quinones, asking him to detail what he’s seen in other states. She said in Maine, her first executive order was to expand Medicaid and her second was to launch efforts to address the opioid crisis.

To that end, she said Maine has greatly expanded the availability and use of naloxone, a drug that can reverse overdoses, enhanced drug courts and instituted a Good Samaritan law so those present during an overdose don’t hesitate to call for help for fear of being arrested.

“It’s one of the great challenges of our time,” Mills said. “People say it’s too big a problem, I can’t deal with it and look the other way. It is happening here and we have to address it.”

Quinones talked about what he called “life repair” for those with substance use disorder — essentially a continuum of care that helps with mental, physical and other needs such as a driver’s license, dental care, new clothes and exercise. He then advocated for a system that makes use of jail time to help people change.

“You have to have a way of taking them off the street, bringing them in to jail, sometimes arresting them for minor things, not because you want to put them in prison, but because it’s harm reduction,” he said. “You have to get them off the streets or they are going to die.”

During a panel discussion, Jeremy Hiltz of Recovery Connections of Maine, said he served time in a Maine jail and that they are not prepared to provide the types of services Quinones is suggesting.

“To prescribe a county jail as treatment of a medical issue doesn’t support data and it doesn’t support science,” he said. “I don’t want to see any of my brothers and sisters incarcerated for anything.”

U.S. Attorney Darcie McElwee asked if there are short term solutions worth pursuing, such as strengthening existing re-entry programs for former inmates.

Quinones said while he isn’t from Maine, his research in Kenton County, Kentucky showed they instituted the successful program in about nine months. The program, which began in 2015, offers treatments that include medication, cognitive and behavioral therapies and community referrals, according to addictionpolicy.org.

“It seems to me rethinking jail is a wonderful way to go about it,” Quinones said. “You could save a lot of lives if you do that.”