New federal data on greenhouse gas emissions paints a picture of Maine as a state with huge opportunities in storing carbon in its forests — and shows the persistent impact of fossil fuel use.

The Environmental Protection Agency released newly detailed data on each state’s emissions sources from 1990 to 2019, with new tools to help policymakers chart a path to lower emissions.

We broke down these numbers to learn more about Maine’s contributions to the global rise in temperatures, and looked at what this means for the state’s ambitious climate change goals.

In 2019, Maine’s net emissions were about 7.1 million metric tons of greenhouse gas – including both emissions sources and “sinks.” Maine would emit more than twice as much without its carbon-storing resources, particularly forests, which cover more of Maine than any other state.

“Maine’s ability to continue to store carbon in the future is going to depend on the ability to maintain the high forest cover that we currently have,” said University of Maine associate professor William Livingston, the interim director of the School of Forest Resources.

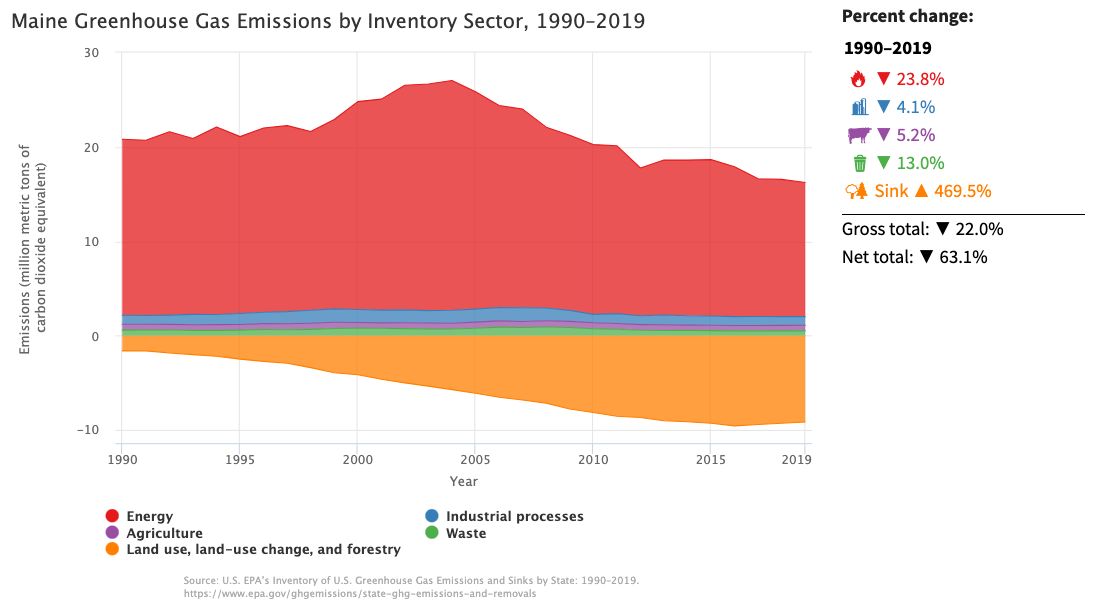

Without that storage, the data shows, Maine’s emissions have declined 22% since 1990. With storage, net emissions have declined even more, down 63% since 1990.

Even so, the state’s most recent net emissions were equivalent to that of 1.8 coal-fired power plants or more than 1.5 million passenger vehicles driven for a year, according to an EPA calculator. The state would need 1,474 wind turbines or another 8.7 million acres of forest to absorb those emissions and reach carbon neutrality, which Maine aims to do by 2045.

The vast majority – 87.5% – of the emissions the state is working to reduce come from the burning of fossil fuels for energy. Industrial activity and its chemical uses contribute 5.6%, and waste and agriculture make up the balance.

Emissions from energy in Maine are down nearly 24% since 1990. The state’s climate plan says the biggest sources in that category are light-duty vehicles and heating oil use in buildings. Lawmakers and regulators have prioritized those in their emissions-cutting efforts to date.

Maine contributed 0.1% of the nation’s net emissions and 1.1% of its carbon storage as of 2019.

The U.S. overall is the second biggest contributor to global emissions, which reached their highest level ever in 2021, erasing the declines seen as the pandemic began in 2020, according to an International Energy Agency report out last week.

Perhaps the most striking statistic for Maine in the new EPA data is how much carbon the state stores in the way it uses its lands – especially by keeping forests as forests.

The state’s lands now store a whopping 470% more carbon than they did in 1990, absorbing more than 9 million metric tons of greenhouse gas in 2019 and helping cut those net emissions by more than half what they would be otherwise.

“We have a lot more trees than we have people,” Livingston said, “and because of that the trees are going to offset the carbon dioxide that people produce through their normal activities.”

The emissions from Maine’s lands – where forests are converted to developments or croplands, for example – have actually increased by nearly 25% since 1990. And the state’s climate action plan projects an increasing loss of “natural and working lands to development.”

But the state’s lands – nearly 90% covered by forests, the highest in the country – are still far and away a net carbon sink. Actively growing forests, managed to keep a healthy portion of young and new trees, will store more carbon year over year. And any cut wood that is not burned or decaying will continue to hold onto the carbon it stored before it was harvested.

The state’s climate plan includes the preservation of forests and other natural carbon sinks as a key strategy to lowering emissions. It says Maine should conserve 30% of its lands by 2030, up from roughly 20% in 2020.

A statewide inventory of “carbon stocks” in Maine’s land and waters is due out next year.