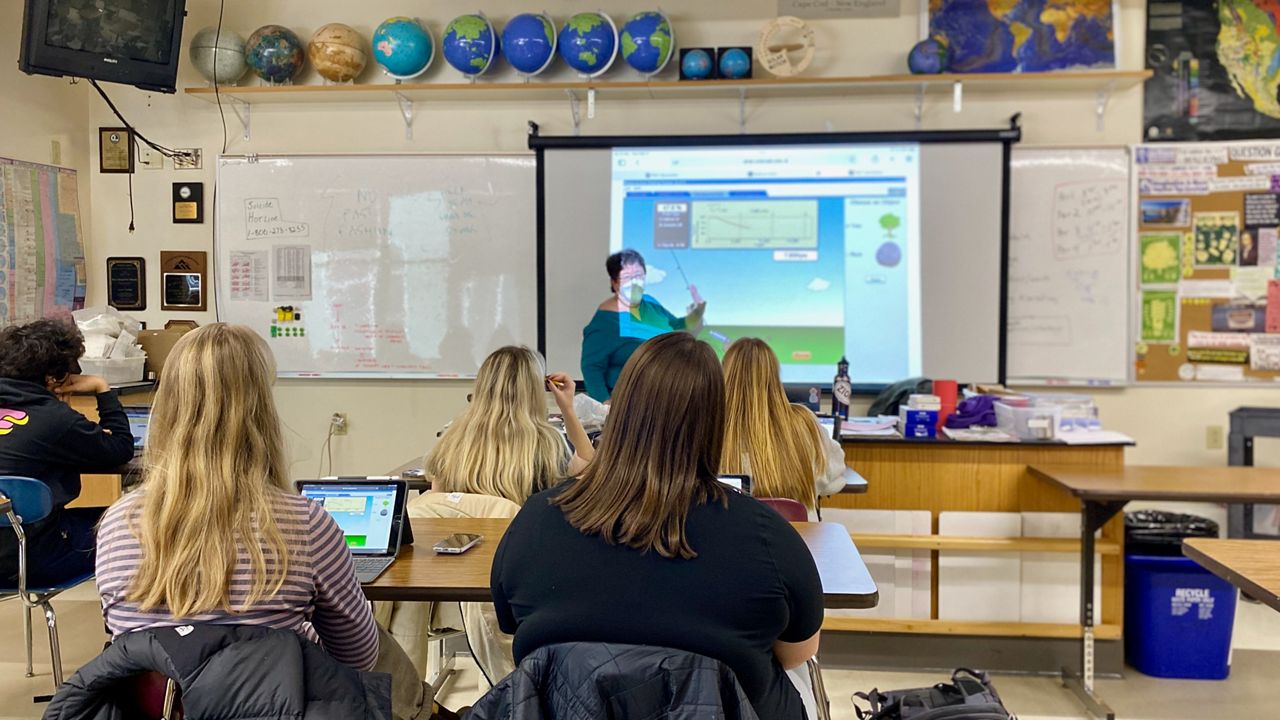

In a basement lab at Camden Hills Regional High School, with posters about recycling and renewable energy lining the walls, Margo Murphy’s freshmen Global Science students spent a recent morning learning how to measure the past, present and future of their changing planet.

They used an online game to practice radiocarbon dating, calculating the half-lives of atoms to estimate the age of organic materials. Next month, students will build on this lesson to learn about Earth’s history of mass extinctions, largely driven by shifts in climate – the same kind of change, as Murphy often explains to her students, as humans are causing now.

“Sometimes these changes can lead to catastrophic things,” Murphy said in an interview while her students worked on the half-life exercise. “And if they’re at the hands of humans, shouldn’t we be doing something about it?”

Murphy has centered this required class on climate change for years, and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) that Maine adopted a few years ago now require all public school students to learn basic climate science and how human activity affects the planet.

But these standards do not guarantee that teachers, especially in elementary and middle school, will know the best ways to meet them — meaning some Maine students still receive minimal instruction on the topic, even with climate education highlighted in the state’s climate action plan and dwindling time to avert the worst effects of warming temperatures.

A bill up for a vote in the state legislature offers a solution — not with new curriculum requirements, but by focusing on voluntary teacher training. It would use $3 million in surplus funding for a three-year pilot program that would create professional development opportunities for teachers to improve their climate instruction skills.

The grants would be required to prioritize “schools and communities historically underserved by climate science education,” such as those in rural areas, with many students of color, English learners, those on free and reduced lunch or in special education programs.

The bill passed the legislature’s education committee this month after a well attended January hearing. It goes before the full House and Senate Wednesday and then would move on to the appropriations committee for a funding decision.

Supporters say the proposal is a first step, though not the last, in empowering more students with the knowledge and tools to respond to a global crisis they are already inheriting.

Kosi Ifeji, a senior at Bangor High School, said their climate education in Maine public schools comprised a two-week unit in a freshman science class, and a research project on why some deny this science for a debate in another class.

“There was no interdisciplinary talk about how this affects different people around the world, because climate change does not affect us all equally and will not affect us all equally,” Ifeji said. “If it really humanized the situation, then people would be more interested and engaged and would be able to actually be inspired to take action and find solutions.”

Ifeji saw missed opportunities for climate work in language arts, history and civics classes, and for more emphasis on the human causes and impacts of the science they learned as freshmen. Their classmate Ogechi Obi, also a senior at Bangor, agreed that this kind of approach would have helped students connect more with a topic that can feel scary and incomprehensibly big.

“I think, almost, it's more important to talk about it in a social setting, because in our everyday life, we don't see the three-degree temperature change; we don't see the one-inch sea rise. We see the effects of different weather patterns – we see the droughts, we see the raise in prices that comes from, perhaps, a bad corn crop and no ethanol for gasoline,” Obi said. “If we had discussed it that way, it would have been more practical and useful for our lives… as opposed to just something esoteric and something just learned to learn and to meet a standard.”

The Maine Principals’ Association said in a letter to legislators that it felt the issue was sufficiently covered by the NGSS and did not merit more funding.

But instructors and educational nonprofits argue that teachers do need more outside support to teach beyond the basics of the topic and an ability to introduce nuance and local applications. And a 2019 survey by the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance, which helped craft this bill, found that climate change was the top area where instructors wanted more professional development.

The Ecology School, in Saco, is one of many Maine nonprofits that could partner with school districts to provide that professional development using the proposed funding.

On the snow-covered hills of the campus above the Saco River, school president Drew Dumsch and communications manager Amalie Sonneborn showed off new green dorms, yurt classrooms and a dining commons topped with solar panels. The Ecology School is the first in Maine to work toward a high-level sustainability certification known as the Living Building Challenge.

Sonneborn said the school uses this built environment in teaching the basics of ecology and humans’ role in nature to student groups who come here – making overwhelming issues like climate change feel digestible, while making learning fun in the outdoors. Students harvest their own food in the surrounding fields, cook it using renewable energy, and see those solar panels up close.

“It draws connections to the human experience in a pretty direct way. We can’t get our energy from the sun the same way that a plant can, but we’ve developed the technology to make that happen,” Sonneborn said. “It’s a way to directly connect oneself to develop empathy to a plant, to the ecosystem, to the components that are making up all of the natural world around us.”

Dumsch said the Ecology School has hosted teachers for environmental education training in the past, and would hope to do more with a focus on climate change if the funding bill passes. Knowing that both teachers and school administrators can be strapped for time, he said Maine’s myriad environmental nonprofits can take initiative to offer ready-made uses for the grant money.

Ian Collins, a former classroom and outdoor instructor who now works for the Maine Math and Science Alliance, said he hopes this approach can be used to reach teachers in and out of the science field who might be leery of taking on the thorny topic of climate change. More training, he said, could help educators see this complexity as a benefit, rather than a barrier.

“I've always thought it's really important as a teacher to not necessarily tell students what to think about any particular issue, and climate change is so politically charged that I really try to steer clear of that aspect,” Collins said. “Just looking at the data provides a unique window into letting students kind of draw their own conclusions … which I think is really empowering for students and results in better learning outcomes if they’re engaging in that process themselves.”

He said this makes climate change a great vehicle, regardless of its importance, to practice data interpretation skills and other earth science principles covered in the NGSS. And, crucially, it offers ample opportunities for students to get in the field to generate their own data from scratch.

Retired Falmouth Middle School science teacher Carey Hotaling, who now works with the Nature-Based Education Consortium, said partnerships are key to enabling that field work, especially for generalist teachers in younger grades who are stretched thin by assessments.

“There are … resources right in your own hometown that could be a benefit to you, but you don't have the time to figure out how and what they are and who they are,” Hotaling said.

She recalled her eighth graders studying invasive species with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in an outdoor project that tied in to warming waters and other effects of climate change.

“As soon as they know about it, they’re not ignoring it anymore,” she said. “And it's really criminal for the adults to ignore it just because it's scary or we don't understand the science of it or it seems too big or the wrong age group or whatever your excuse can be. I think this is a great way to start – with a pilot, just encouraging and with money.”

At Camden Hills Regional High School, Margo Murphy’s freshmen finished up their radiocarbon dating exercise. Amelia Porter, 15, said in an interview that she was glad to have learned more about climate change in one semester of this class than in all of middle school.

“We’re dealing with climate change right now, and it’s going to impact all of our futures, whether we like it or not,” Porter said. “It’s important to learn about that so we can do our best to help not burn the planet.”

Soon after the freshmen left for lunch, two seniors in Murphy’s AP Environmental Science class stopped by to pick up some equipment for another climate-related project. Allison Gill and Elsie Hildreth, both 18, are in one of several classes in the state working with the University of Maine to monitor rising sea levels in various coastal spots — in their case, Rockport Harbor.

“I’m usually pretty aware about environmental stuff, climate change and all that, but this class has still been super eye-opening to me,” Gill said. “Just how much is going on, like, behind the scenes that we don’t really know about that’s affecting the climate.”

Gill plans to study environmental science in college, and Hildreth wants to focus on sustainable design. Those goals were shaped by the outdoor education and, now, climate curriculum they received in school, but even more so by their personal connections to Maine’s environment. Both students are avid skiers, and they’ve noticed how winters have warmed in their lifetimes.

“We care so much about the environment here and our seasons — we love it so much, but the winters have been so disappointing recently … I feel like it’s changing really quickly,” Gill said. “I want to bring back big snowy winters.”

Advocates like Ogechi Obi, the Bangor High School senior, argue that the ideal climate education will build on these lived experiences to empower students to help make change.

“We are in a climate crisis, and I only think that can be combated through education,” Obi said, “because you can't really fight what you don't understand.”

This story was updated Tuesday afternoon with details on the full state legislature's vote on the bill now scheduled for Wednesday. It has also been updated to correct the harbor that Margo Murphy's AP Environmental Science students are monitoring. It is Rockport Harbor, not Camden.