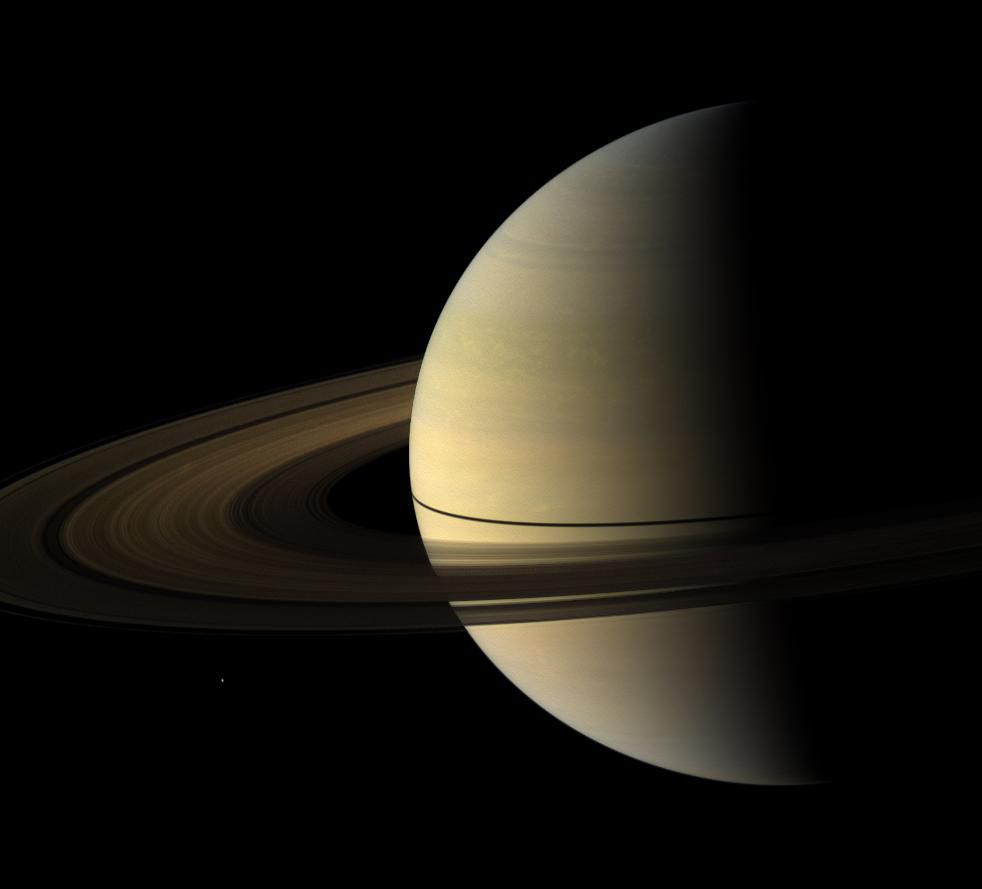

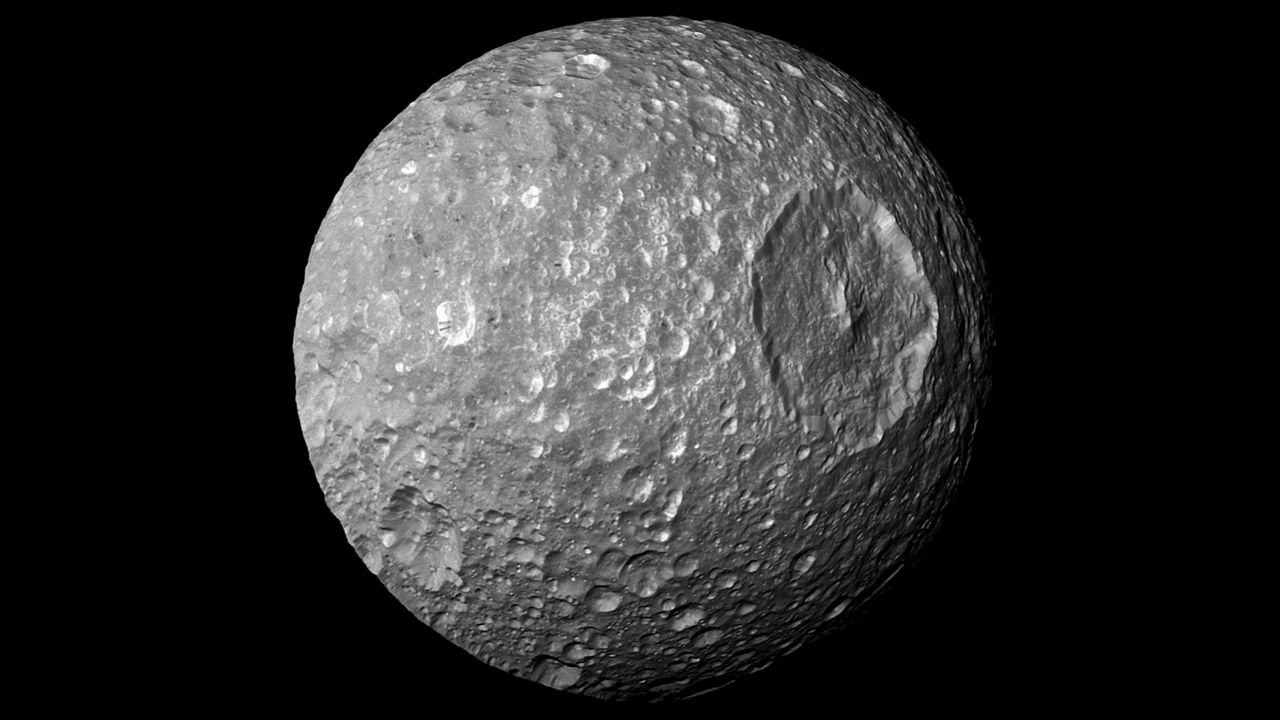

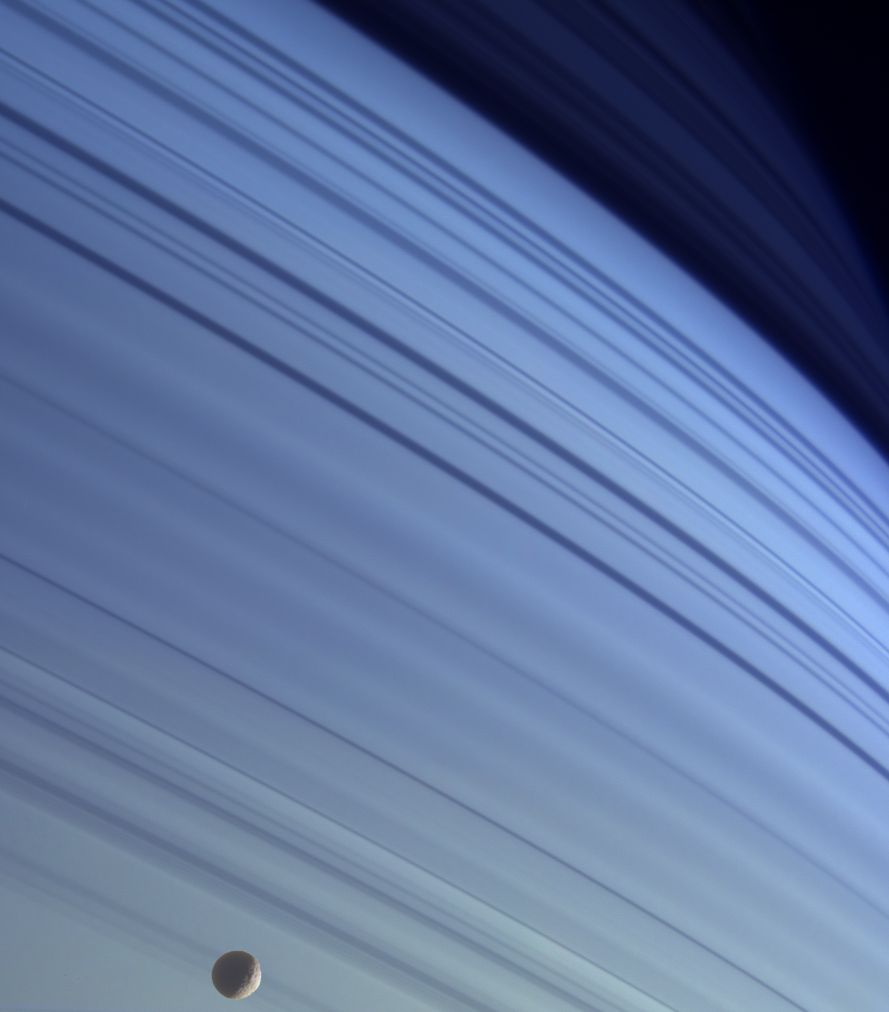

A Maine-based researcher has theorized there's an undetected ocean in our solar system, beneath the surface of a tiny moon of Saturn that bears a striking resemblance to the Death Star from Star Wars.

Matt Walker works from his native Portland as an associate research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona. He worked with Alyssa Rhoden of the Southwest Research Institute on a new paper in the journal Icarus, making the case for a hidden ocean on the moon Mimas.

Click and drag to explore this 3D model of Mimas. Courtesy: Nasa/JPL

One of the largest of Saturn’s many moons, Mimas is still tiny by cosmic standards at about 250 miles wide, close to 10 times smaller than Earth’s own Moon. The rocky, pockmarked surface of the slightly ovoid Mimas includes a massive crater – more than 6 miles deep with a central mountain nearly 4 miles high – that earns it the Death Star comparison.

“It does look kind of dead, kind of boring,” Walker said in an interview. “But that’s what’s most exciting about it, is that we think it’s not.”

Scientists have detected ice miles beneath Mimas’ surface, but its exterior doesn’t show the visible activity of other moons in the solar system – such as Jupiter’s Europa or Mimas’ neighbor of Saturn, Enceladus – that are thought to have liquid water, a key building block of life.

If the same is true of Mimas, it would open a new class of what Walker calls “stealth ocean worlds,” possible both in our solar system and for so-called exoplanets outside of it. These places are one short list for potential life beyond Earth.

“To find (liquid water) on these places that are generally overlooked is really cool because now we have lots more places to look,” he said. “And then what’s really, really cool is … we might be able to now know, these are the types of scenarios that could create liquid water, so we can find it not just in our solar system but theorize at least that it might be present in other places too.”

Walker and Rhoden looked for Mimas’ ocean using models of the heat that the tidal pull of Saturn exerts on the moon, and by estimating the density and movement of its subsurface in many layers to see where there might be rock, ice or liquid.

He said they had a “Eureka moment” when their estimate for the thickness of Mimas’ icy shells matched those of a previous study. Walker’s focus is using this kind of tidal heating model on other celestial bodies, which could aid in the search for liquid water and habitable worlds.

“If there was going to be life anywhere on Europa and Enceladus, and now Mimas, too, we think it would be deep in the oceans, probably around hydrothermal vent systems, kind of like we have on Earth,” he said. “It wouldn't be, like, whales or anything like that – it’d be mostly bacteria-style stuff that would exploit the energy, the heat, from those thermal vents. I wish it was whales, though.”

As he creates these models with computer code, trying to understand the secrets of strange moons hundreds of millions of miles away from his home in Maine, Walker is also awaiting real-world data from NASA missions to test his predictions.

He’ll be able to use some findings from the Juno probe, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, but said he is especially excited about the Europa Clipper, an orbiter that will study the gravity and chemistry of that moon of Jupiter after its scheduled launch in late 2024.

Europa is also thought to have liquid water beneath its icy surface and has been a focus for scientists as a “very obviously active ocean world,” Walker said. With insights from that upcoming mission, he’ll be able to test and refine his work on tidal heating.

“We build these models with the best things we have and often that's data from the '80s, '90s,” he said. “Getting some new data with the advances we've made in the last multiple decades is going to be ridiculously awesome to constrain the stuff we're doing, so I am pumped for that.”